On the 65th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education II: Implementing a Sweeping Change

This year’s high school seniors understandably feel cheated by the cancellation of graduation ceremonies and other rites of passage due to the coronavirus. Yet as I listen sympathetically, I find myself thinking about an earlier generation who willingly gave up their moment of celebration with friends and teachers.

Three generations ago, small groups of African American students left friends, nurturing teachers, and familiar rooms behind as they challenged segregated schools across the South. They enrolled in formerly all-white schools, asking for the educational opportunities of their white peers—new textbooks instead of worn-out discards, modern laboratories for science experiments, a full academic curriculum. To gain these advantages, they would study among strangers, and many would graduate without feeling fully accepted by classmates or encouraged and congratulated by teachers.

The Supreme Court Rulings, and Their Limitations

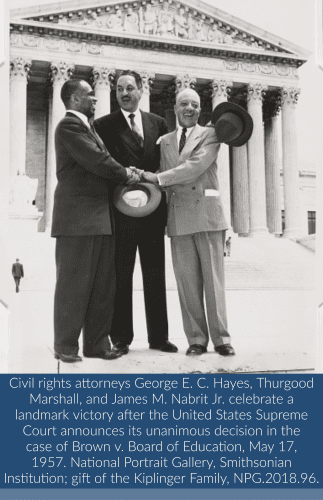

They had to challenge segregation despite the passage of two landmark decisions on school desegregation, both called Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The first decision, on May 17, 1954, had declared “the fundamental principle that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional” and had found the legally segregated schools of the South to be “inherently unequal.” Desegregating those schools would be required. Yet it would mean reorganizing every school district in the South, a vast undertaking.

Although named in the title of the case, the Board of Education of Topeka was but one of five separate cases in four states and the District of Columbia that had been argued as one. The ruling in Brown II, issued on May 31, 1955, essentially remanded those cases to the courts that had originally heard them, reasoning that, since “full implementation of these constitutional principles may require solution of varied local school problems” and “school authorities have the primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these problems,” it would be necessary for the local courts, which would be most aware of what the challenges were, to “perform this judicial appraisal.”

Although named in the title of the case, the Board of Education of Topeka was but one of five separate cases in four states and the District of Columbia that had been argued as one. The ruling in Brown II, issued on May 31, 1955, essentially remanded those cases to the courts that had originally heard them, reasoning that, since “full implementation of these constitutional principles may require solution of varied local school problems” and “school authorities have the primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these problems,” it would be necessary for the local courts, which would be most aware of what the challenges were, to “perform this judicial appraisal.”

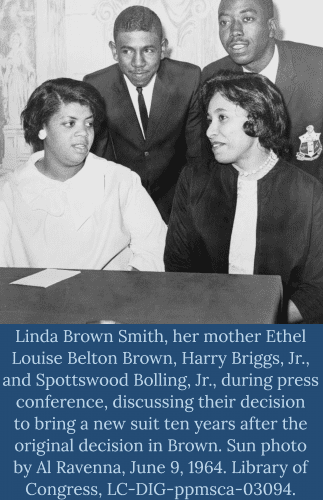

Potentially, this meant that new lawsuits would have to be brought against every other school district reluctant to end de jure segregation. Although a few school districts immediately made plans to comply with Brown, most did nothing. In the meantime, the federal district court in South Carolina that reconsidered Briggs v. Elliot, one of the five cases remanded by Brown II, interpreted Brown I to mean not that “states must mix persons of different colors in the public schools” but rather that “a state may not deny any person on account of race the right to attend any school that it maintains.” In other words, black families could apply for the privilege of sending their children to formerly all-white schools.

Strategies for Minimal Compliance

Seizing on the “Briggs Dictum,” many southern states enacted “freedom of choice” laws that allowed for only token integration of schools. They also enacted “pupil placement” laws that set up requirements for admission of the black students, such as attestations of their polite and respectful demeanor or high scores on academic tests.

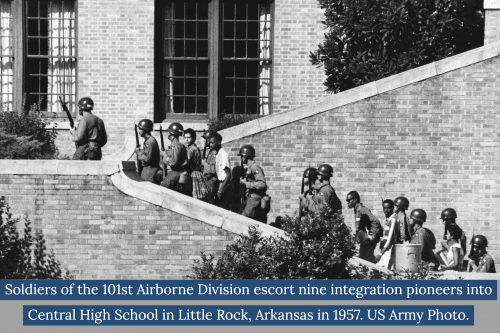

A small fraction of black families took up the challenge of such laws. In some places, such as Greensboro, NC, black students were admitted without negative incident. In other places, white students and family members reacted angrily, even violently. At high schools in Charlotte, NC and Little Rock, AR, white parents and students tried to thwart implementation of the Brown decision by harassing black students as they entered school buildings and making the school day so miserable for them that they would abandon the integration effort.

Nine black students entered Central High School in Little Rock in 1957 under the escort of federal troops; eight managed to stay throughout a school year, despite daily harassment. The one senior in the group, Ernest Green, did become the first black graduate of Little Rock High School. Martin Luther King quietly accompanied Green and his family to the ceremony; so did National Guard troops.

Nine black students entered Central High School in Little Rock in 1957 under the escort of federal troops; eight managed to stay throughout a school year, despite daily harassment. The one senior in the group, Ernest Green, did become the first black graduate of Little Rock High School. Martin Luther King quietly accompanied Green and his family to the ceremony; so did National Guard troops.

School Integration Mandated by Congress

With passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, school desegregation gained legislative backing. Opponents knew they had lost. School districts began to implement desegregation plans, but until the Briggs decision was successfully challenged (mostly notably in a 1966 federal court case, United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education), many offered only the “freedom of choice” option. Hence the need for “integration pioneers,” black students who volunteered in school districts across the South to jumpstart the integration process.

Last year we published an interview with one such student, Gloria Sloan, who said that being an integration pioneer meant that “I sacrificed my junior and senior proms. I lost a close connection with the students still at [my former school] that I had been friends with in the earlier grades.” More troubling, she received no counseling or support as she applied to colleges. “As my time at the high school drew to a close, it seemed they were saying to me, ‘You broke the ice and showed that integration could work. You’ve done your work—you can go now,’” Sloan recalled.

Most integration pioneers did go on to college and successful careers. They did help to bring about integration in business and other areas of Southern life. In a few cases, Sloan’s included, the courage of the integration pioneers led to immediate and full integration of school systems. In other cases, token integration prevailed until the early 1970s. Meanwhile, desegregation acquired a new cause for contention as federal ajudges sought a “numerical balance” of races reflective of the local population. Segregated patterns in housing meant that in many school districts racial balance would require busing students out of the neighborhoods in which they lived. This was an ironic destination for a judicial process that began when students like Linda Brown of Topeka were denied the right to attend white schools within walking distance of their homes.

Most integration pioneers did go on to college and successful careers. They did help to bring about integration in business and other areas of Southern life. In a few cases, Sloan’s included, the courage of the integration pioneers led to immediate and full integration of school systems. In other cases, token integration prevailed until the early 1970s. Meanwhile, desegregation acquired a new cause for contention as federal ajudges sought a “numerical balance” of races reflective of the local population. Segregated patterns in housing meant that in many school districts racial balance would require busing students out of the neighborhoods in which they lived. This was an ironic destination for a judicial process that began when students like Linda Brown of Topeka were denied the right to attend white schools within walking distance of their homes.

Losses and Gains

Looking back, some have questioned what was gained, and what lost, in the school integration process. Did black communities lose a key source of support for their youth? Especially in larger cities, many of those who taught in segregated black schools were unusually well educated, having been barred from work in the professions they aspired to. Yet, inevitably, as integration progressed, many of these highly educated teachers would leave the education field. Others have wondered whether Brown slowed the overall cause of civil rights, since it provoked so much angry resistance. Yet such resistance, too, seems inevitable. School desegregation took aim at the deepest motives of the Jim Crow system. One of these was a longstanding effort to keep a race under-qualified to assume professional and white-collar jobs, so that they would remain available as an inexpensive labor source. The other was the long-held fear of racial “mixing,” which would undermine the claim that the races were distinct in manners and abilities. Both motives faced the most bitter opposition. Yet both had to be overthrown. Those young people who pioneered school integration deserve a nation’s thanks.