Roger Williams: From Dissent to Consent and Covenant

Sarah A. Morgan Smith

October 6, 2020

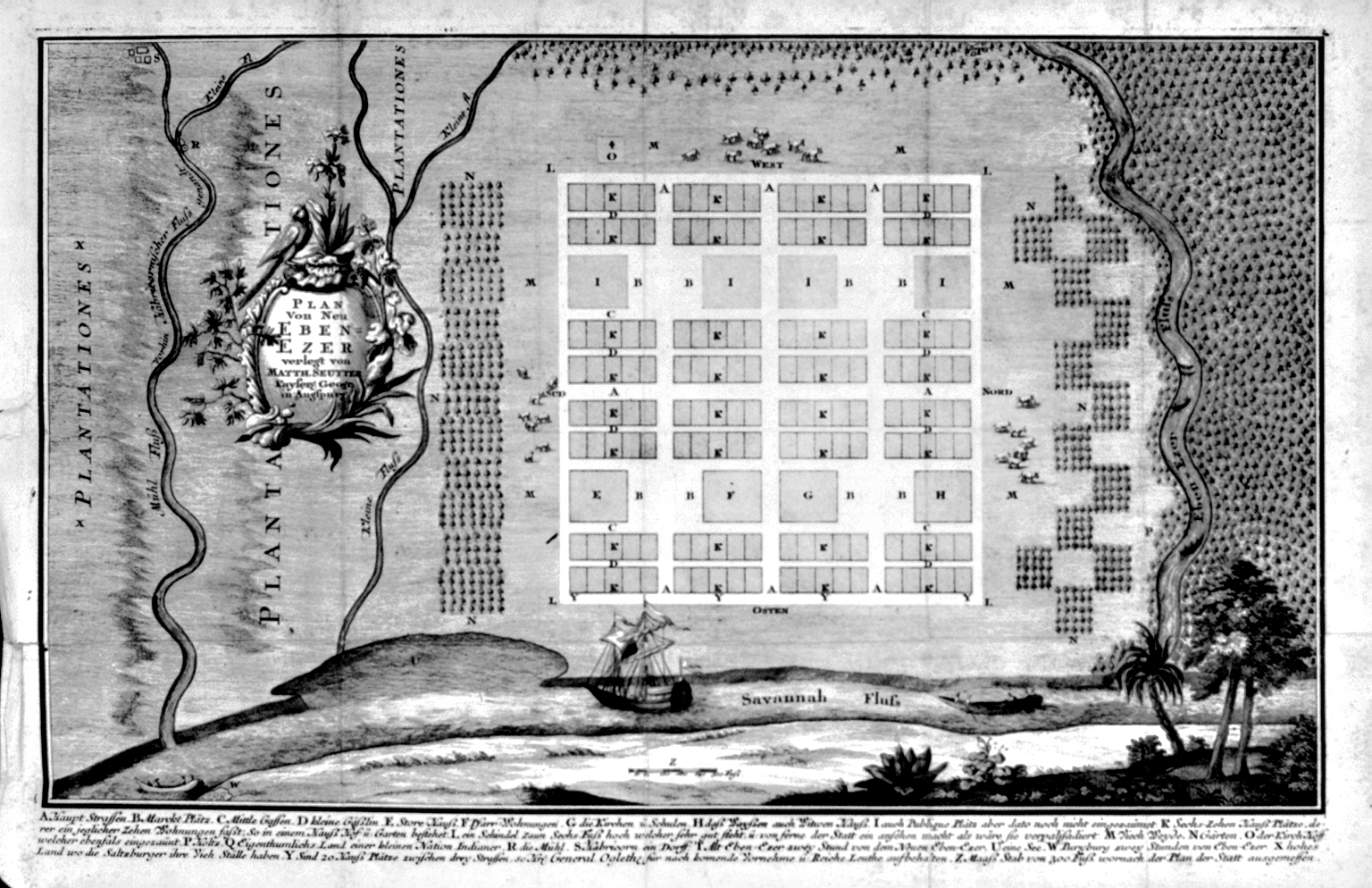

Talented and charismatic as a minister, Roger Williams was a radical even by the standards of Puritan Massachusetts when it came to the pursuit of holiness. Williams—who is most often remembered today as a champion of religious liberty—was something of a schismatic in his own time, refusing to worship or share communion with those whose positions on certain theological questions differed from his own. Williams’ criticisms extended to civil matters as well, leading him into conflicts with the government of the colony. After several years of stirring up trouble in Massachusetts Bay, Williams was banished from the colony on October 9, 1635 for having “broached and divulged diverse new and dangerous opinions, against the authority of magistrates,” and “also writ[ten] letters of defamation, both of the magistrates and churches here.” Rather than face deportation, Williams fled the colony and spent the winter among the local Wampanoag tribe. By the spring of 1636, he had negotiated agreements with both the Wampanoag and the neighboring Narragansett tribe for land at the headwaters of Narragansett Bay in 1636. There, joined by several families from his previous congregation, Williams established the first settlement, eventually known as Providence, in what would eventually become the colony of Rhode Island.

Although he had been unable to live peacefully as a resident of the Bay Colony, it appears that Williams remained on good terms with Massachusetts’ leaders in both church and state. He maintained regular communication with colony governor John Winthrop, for example. Indeed, early on, Williams wrote to Winthrop for advice about organizing the civil government for the new community. Williams had purchased the land from the natives outside the bounds of the Massachusetts grant, and the community that gathered around him was as yet without a royal charter, so Williams might easily have seen the settlement as simply his own manorial estate. Instead, he invited all the heads-of-households who had come to his land to participate in the governance of the community. As he explained to Winthrop, “the masters of families have ordinarily met once a fortnight and consulted about our common peace, watch, and planting; and mutual consent have finished all matters with speed and peace.” This informal arrangement worked well enough for a time, but Williams was anxious about the long-term future of his new plantation. Would it be wise, he queried Winthrop, to adopt a written agreement, spelling out how decisions were to be made, something along the lines below?

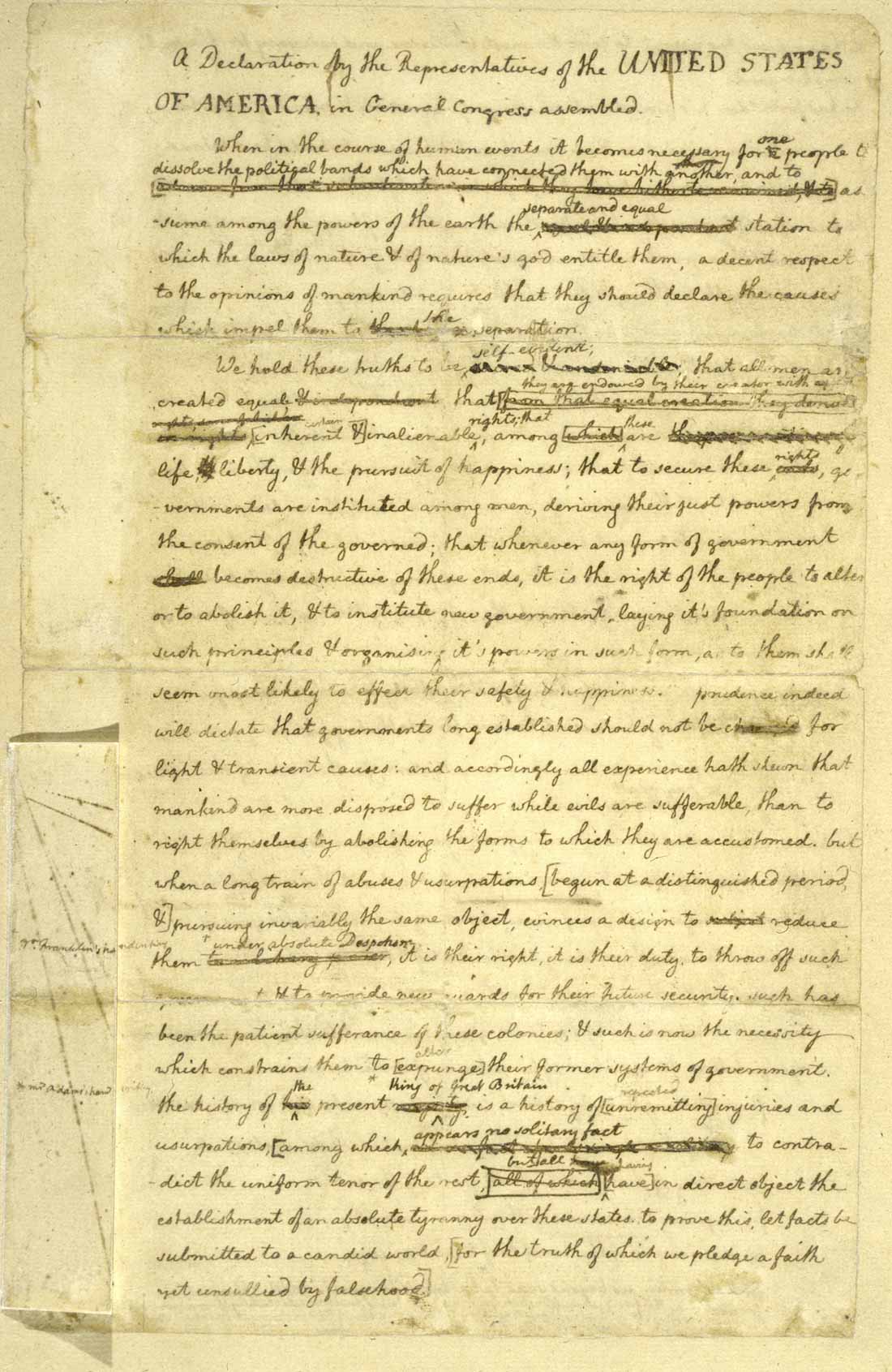

We whose names are hereunder written, late inhabitants of the Massachusetts, (upon occasion of some difference of conscience,) being permitted to depart from the limits of that Patent, under the which we came over into these parts, and being cast by the Providence of the God of Heaven, remote from others of our countrymen amongst the barbarians in this town of New Providence, do with free and joint consent promise each unto other, that, for our Common peace and welfare (until we hear further of the King’s royal pleasure concerning ourselves) we will from time to time subject ourselves in active or passive obedience to such orders and agreements, as shall be made by the greater number of the present householders, and such as shall be hereafter admitted by their consent into the same privilege and covenant in our ordinary meeting. In witness whereof we hereunto subscribe, &c.

In addition to this “subscription,” surely it was only just, Williams wrote, for him to “desire this of my neighbors, that as I freely subject myself to common consent, and shall not bring in any person into the town without their consent : so also that against my consent no person be violently brought in and received.” In other words, Williams wished to maintain a level of control over the inhabitants of his new settlement similar to that exercised by the governor and council in Massachusetts—to determine who would and would not be tolerated as a neighbor.

Williams was successful not only in attracting new neighbors to his plantation, but in securing a royal patent recognizing his authority over the region to the exclusion of competing claims put forth by other Massachusetts dissenters like William Coddington (a compatriot of Anne Hutchinson who left Massachusetts shortly after the Antinomian controversy). Yet his success did not come without contention: in the 1650s, Williams found himself embroiled in a factious mess over the control of the colony that led him to write to his “well-beloved friends and neighbors” in admonishment. Other dissenters with a variety of religious opinions had migrated to the area around Providence, established their own settlements, and were attempting to secure royal charters in competition with Williams’ own. Williams’ solution was to unify the diverse towns under a single colonial government–one based on the power of civil consent even in the face of difference, rather than doctrinal purity.

Having exhausted himself “to keep up the name of a people, a free people, not enslaved to the bondages and iron yokes of the great (both soul and body) oppressions of the English and barbarians about us, nor to the divisions and disorders within ourselves,” he was disheartened to see the community so disordered. This was what critics of religious dissenters always claimed would happen, he pointed out: that liberty would devolve into chaos and contention. Having won recognition of his authority over the new colony in the English legal system, Williams now offered conciliation as both an inducement to and a model of unity. He advised his neighbors to relent in their fighting and remember that they were all the beneficiaries of God’s “wonderful Providences, by which alone this town and colony, and that grand cause of Truth and Freedom of Conscience, hath been upheld to this day.” Williams advised the people of Providence to adopt a spirit of love towards their former opponents and to unite with the neighboring towns in a single colony. All the people of the several towns ought to be invited to “meet with, and debate freely, and vote in all matters with [the inhabitants of Providence]” on equal terms, he advised.

What is striking about Williams in these two episodes from the early years of the Rhode Island colony is his consistent stance in favor of consensual government, even when it cost him greatly. Williams did not dispute the right of the Bay Colony’s leaders to dismiss him from their fellowship; rather, as seen in his letter to Winthrop about the Providence “subscription,” he tacitly accepts the proposition that a community covenanted together for purposes of mutual benefit may, by majority consent, exclude others from membership. Yet when his neighbors in Providence attempted to exercise their exclusionary rights in the 1650s, Williams urged them not to do so, and to accept the unified colonial government he had ventured to England to gain—apparently, without their full consent. A dissenter, exiled for his rigid pursuit of church purity, Williams became an advocate of a more minimal vision of civil unity. The community he built would not commit itself to a single theological view. Instead, it would commit to respecting the equal rights of all members in matters of conscience, even if that meant tolerating a rather robust debate on such matters.