Political Parties

Political parties have a long and often convoluted history in American politics. Parties were initially anathema to the Founders and the system laid out in the Constitution was explicitly designed not to be reliant on political parties. To the Founders, parties were factions that threatened to divide the nation into competing groups that, at the worst, could turn to violence to advance their interests (See Federalist 10). The Founders also feared that parties would disrupt the separation of powers. This would be especially true in the case of unified government where loyalty to party might come to interfere with the system of checks and balances. Finally, the Founders worried that political parties might stand in the way of effective representation. Elected officials with party affiliations might be tempted to only represent those of their own political party and leave party opponents without a voice. Given these concerns, it is little wonder that the Founders did not want parties participating in American government.

Yet within ten years of ratification of the Constitution, political parties were alive and well in American politics. Clearly this was not party politics as it is now known, but there was a rough party system and partisanship was as pronounced as it was divisive. This leads to an interesting conundrum – how did the political system become partisan within such a short time after the formation of a government designed to avoid reliance on political parties? Probably the leading answer to this question is that parties were understood as being inevitable. More precisely, republican government does not work well without being buttressed by political parties. Parties have proven to be instruments through which voters can make choices about the policy direction of the country. Parties allow minorities to form coalitions to create majority rule, even if that rule is not always harmonious or stable. Parties help build support for officeholders and serve as conduits of communication to the masses and vice versa. Parties serve as schools of democracy where citizens learn to associate and become attached to governing institutions. Finally, parties mobilize voters and encourage voter participation at all levels of democratic politics.

Inevitable or not, the party system did not emerge all at once: it grew and developed through several distinct political eras. The first of these was the Federalist Era where, under the influence of Alexander Hamilton, the Federalists embarked on an ambitious set of projects to develop an industrial, commercial economy, strengthen the presidency and the courts, and set out broad terrain for the president to exercise vast powers in the realm of foreign affairs. These projects and others were soon opposed vigorously by Madison and Jefferson, with Jefferson eventually allowing himself to be placed as the head of the opposition party. Madison and Jefferson’s growing partisanship was easy for all to see (See “Parties”, “A Candid State of Parties”, and Letter to Philip Mazzei). To be sure, these were not the highly organized political parties of the later nineteenth century but tended to be united behind strong individuals and maintained a more informal organizational structure. The parties did make use of the press, but it was still in its infancy and only a few party newspapers published party writings and attacks on opponents.

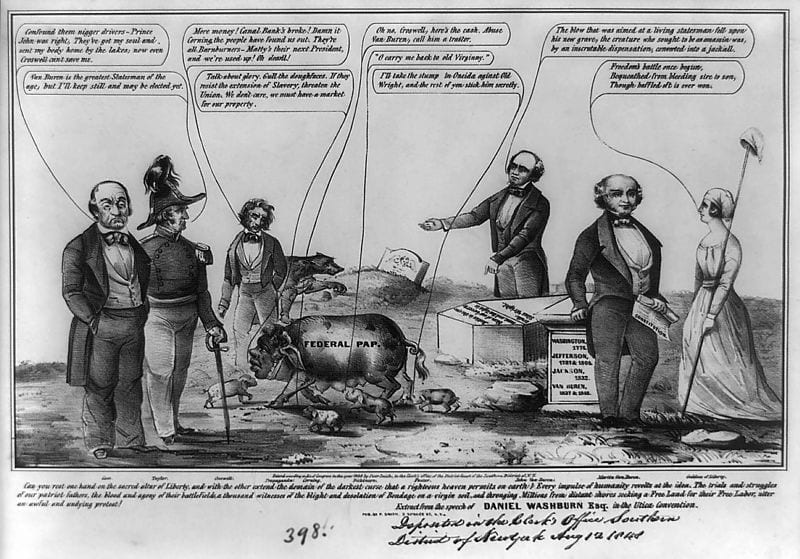

This new party, ultimately called the Democratic-Republican Party, saw victory in the election of 1800, thus marking the beginning of the second party era. Under Jeffersonian and then Madisonian rule, the Federalists began to wither and die as an opposition party and the country was left under one-party rule. But without an opposition to unite them, the Jeffersonians soon found themselves internally divided on issues ranging from war to internal improvements. This led to a fissure in 1824 with several different candidates contending for the presidency. This led some individuals, such as Martin Van Buren, to begin to argue for a wholesale reorganization of the party system (See Letter to Thomas Ritchie and Autobiography).

The late 1820s began the third era of party development, the establishment of permanent two-party competition in America. Martin Van Buren played a major role in making this change possible. For Van Buren, the American electoral system was plagued with several major flaws that needed correcting. It was prone to factionalism with several candidates trying to win over different parts of the country to make the runoff election in the House. It encouraged perpetual campaigning with nothing to formally begin and end the campaign process. It fostered demagoguery with nothing to moderate the messages from the candidates. And it suffered from lack of legitimacy with elections to be decided by the House of Representatives instead of the Electoral College.[1] Van Buren’s solution to all these problems was permanent two-party competition for America, and he began carrying out his vision by recruiting Andrew Jackson to form a new political party to compete in American politics (See Letter to Thomas Ritchie and Autobiography). Thus was born the Democratic Party which has been a fixture in American politics ever since.

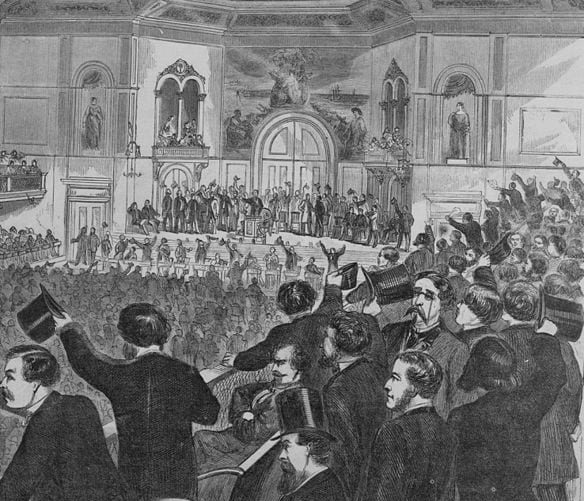

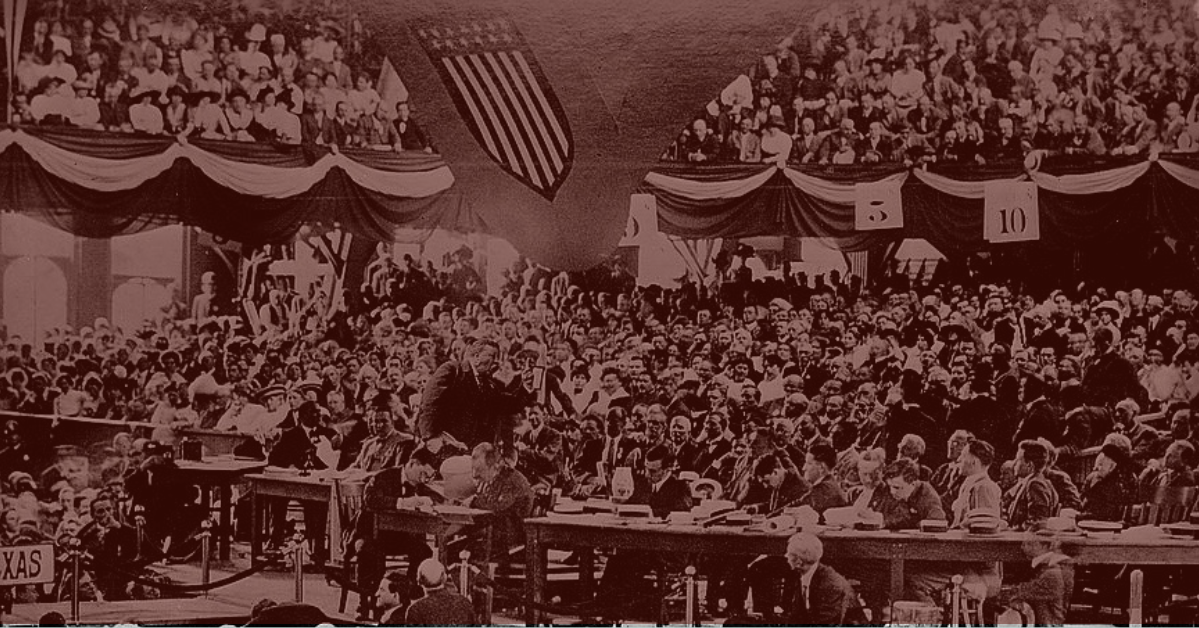

A few years later, the second part of Van Buren’s equation came into being with the birth of the Whig Party. Steadily increasing rates of voter turnout were one sign of the influence that the parties were having on American politics. This is not to say that voting was always well informed, but it was carried out by millions of Americans each election cycle. The parties at this time also developed the convention system for nominating candidates to office. Starting at the local level, conventions would meet to nominate delegates to the next convention level going all the way up to the national conventions. These conventions were highly participatory and helped reflect voter choices in the selection of national candidates.

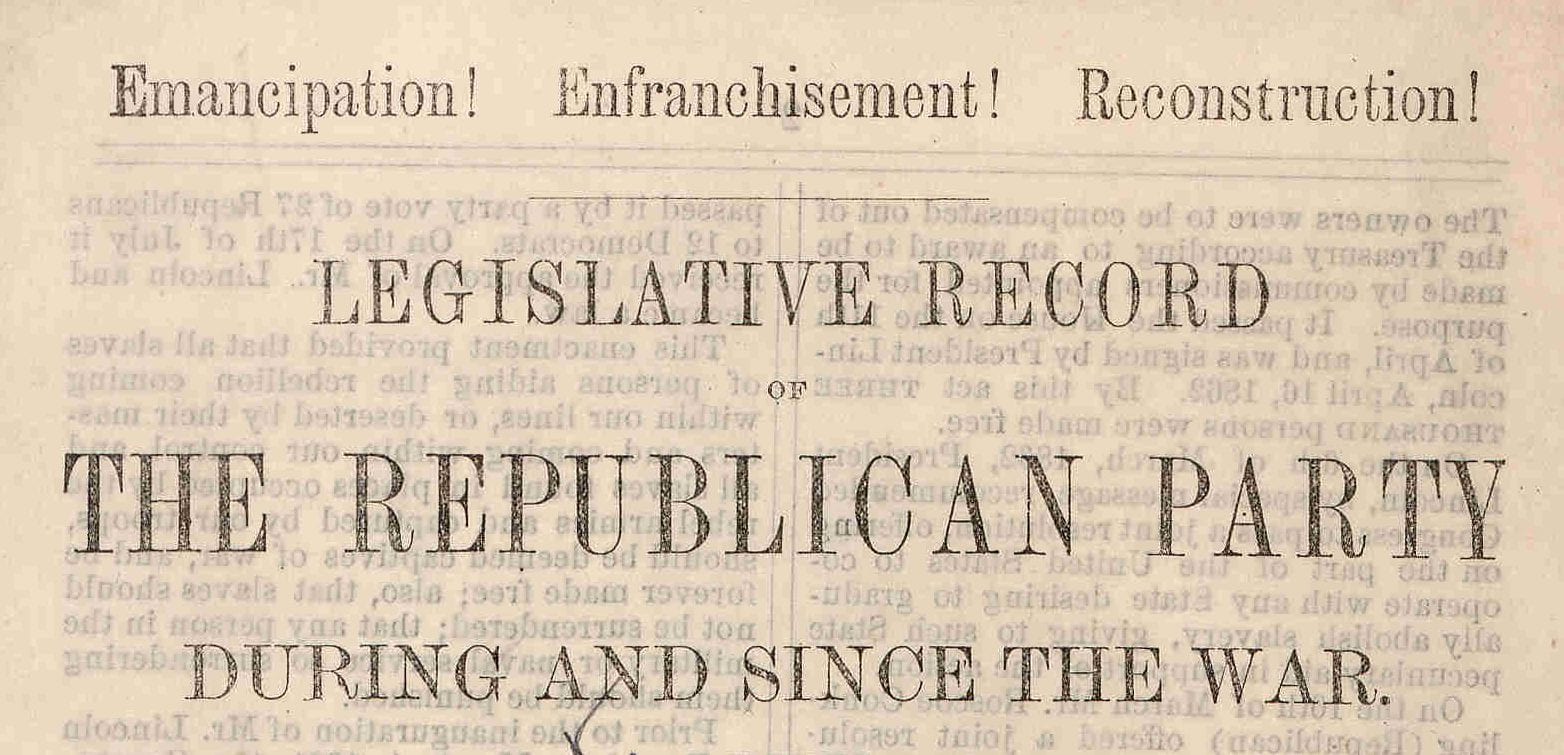

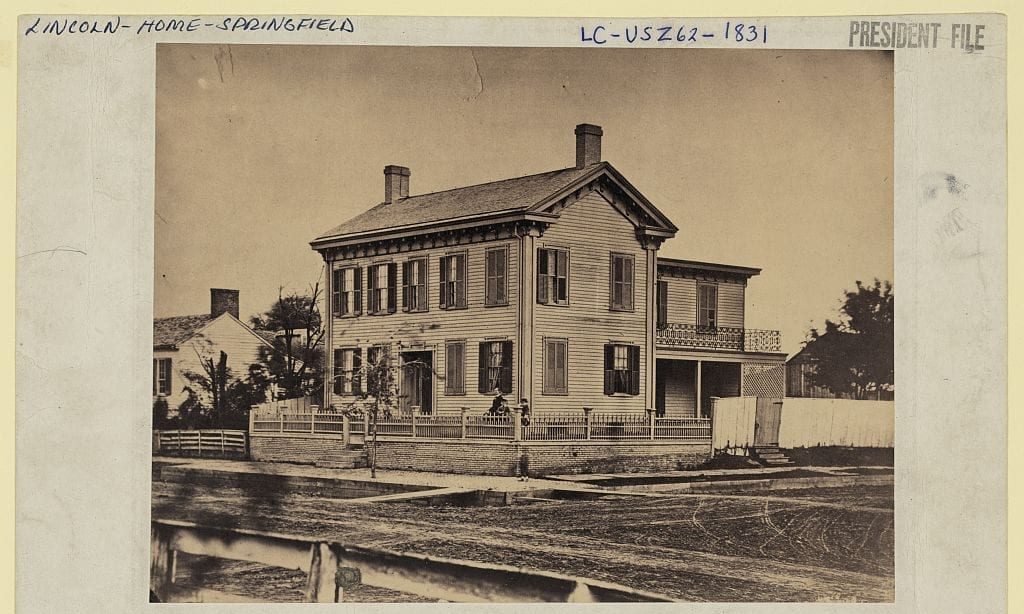

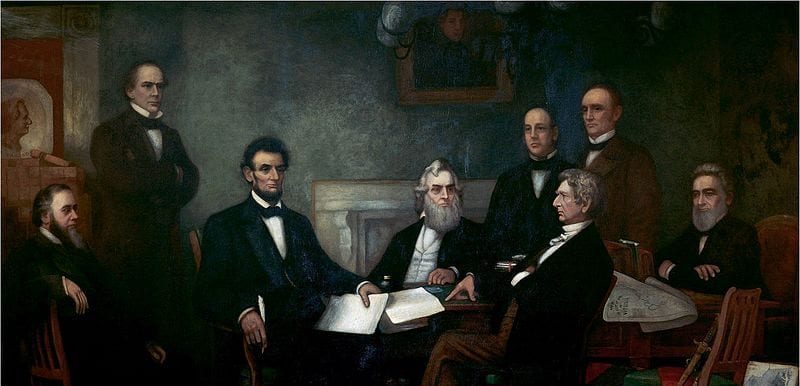

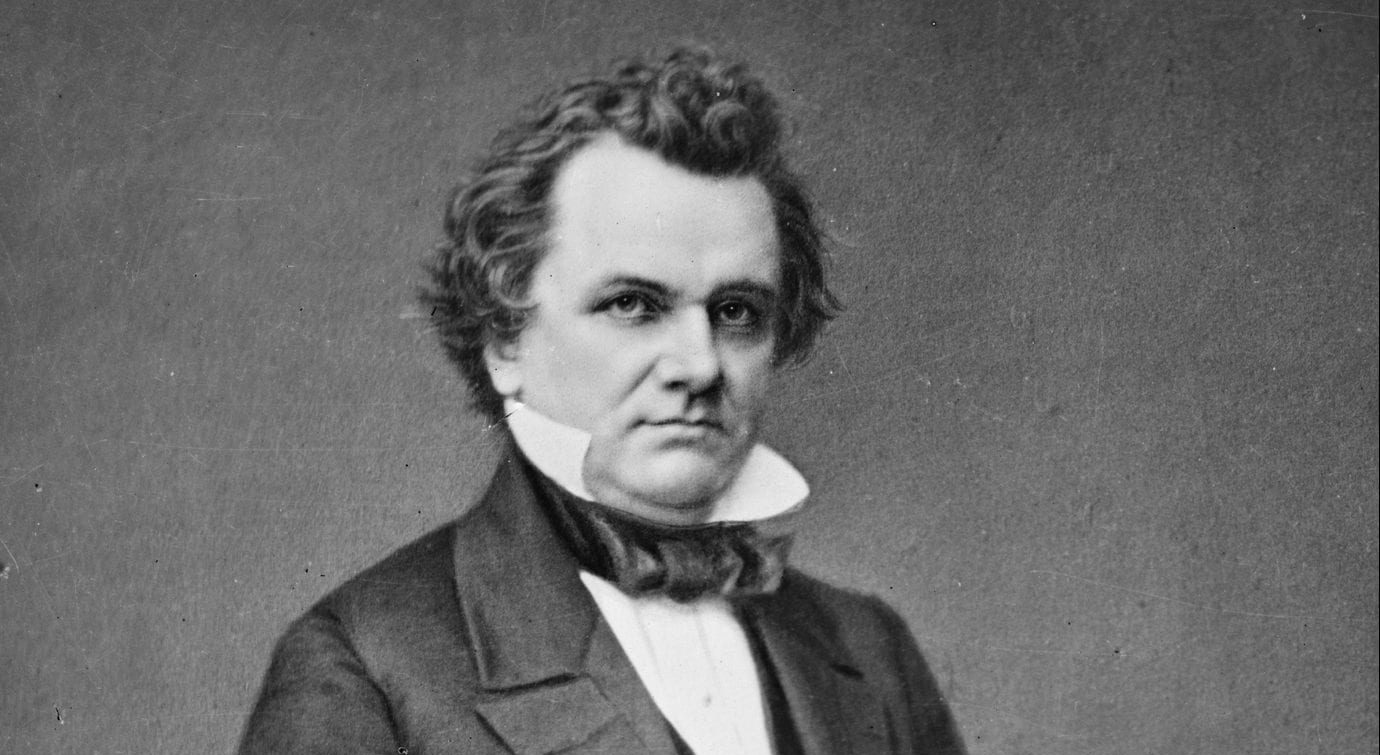

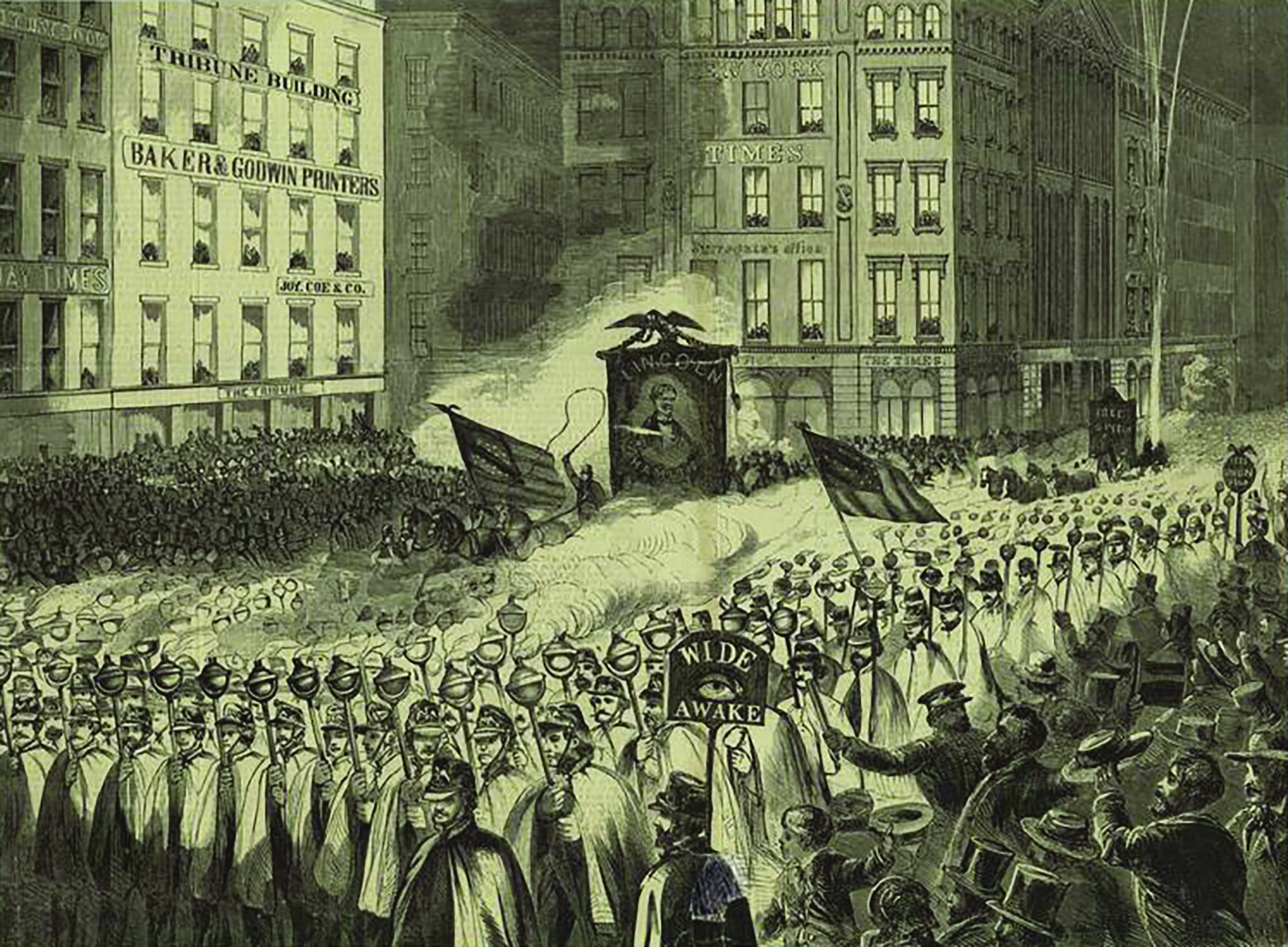

The fourth era of American party development came with the demise of the Whig Party. The Whigs largely defined themselves as being opposed to Andrew Jackson. Once Jackson left office, the Whigs were left with a void in their policy stances. They did support internal improvements and tended to take hard stands on moral issues. The one moral issue they refused to address, however, was slavery. The Whigs joined in the various compromises on slavery that the parties negotiated to keep the sections at peace with one another, but they did not take a hard stand on the immorality of slavery or oppose its spread into the territories. As the abolitionist movement grew in scale and influence, pressure mounted on the Whigs to take a position. When they failed to do so, a new political party was formed that eventually replaced the Whigs – the Republicans. The election of the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, precipitated the Civil War, and Lincoln’s victory in that war gave Republicans ascendency in American politics for a long time to come (See Republican Party Platform 1860, (Northern) Democratic Party Platform 1860, and (Southern) Democratic Party Platform 1860). At the same time, the two parties that would define American politics for the future were now firmly in place and Van Buren’s vision of permanent two-party competition seemed to have come to fruition.

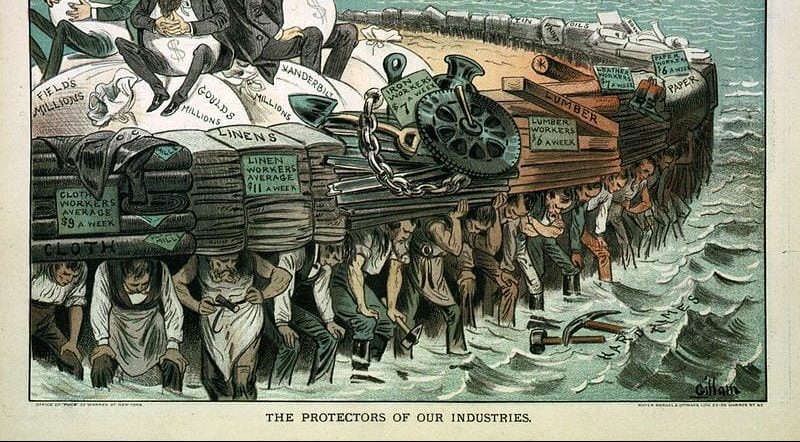

By the end of Reconstruction, the parties were once again on equal footing and they began trading election victories and control over the patronage, also known as the spoils of victory. For the winning party, this meant installing party loyalists into positions in the bureaucracy, exchanging jobs for vote support. This period of time represents the apex of party control and influence over the electorate. For some, participation in a political party took on an almost religious dimension, providing a sense of identity as well as purpose as they worked to further the party’s political agenda. This is the era when bosses, politically influential individuals who control votes and appointments, emerged to run the big city machines that featured widespread corruption but also provided useful social services to their constituents (See Plunkitt of Tammany Hall). These machines were party organizations, usually headed by a boss, that secured enough votes to maintain control of a city, county, or state.

Voter turnout was never as high as it was during this post-Reconstruction Era and parties did a superlative job mobilizing voters and getting their people to the polls. Corruption at the polls certainly took place, but it tended to be particularized to certain areas and was definitely not all encompassing given the sheer number of voters participating. This period might truly be called the Golden Age of parties, which were considered a natural and organic part of the political system. Third parties also continued to emerge during this era including the Prohibition Party, the Greenback Party and the Populist Party (See Populist Party Platform 1892), though all were overshadowed by the dominance of the two-party system. This shows that there were undercurrents of discontent among the American electorate, but for the time being the two major parties were able to manage it.

In the 1890s, the course of American party eras becomes a bit murky. It becomes difficult to define what constitutes an era and what marks the beginning and ending of eras in the permanent two-party landscape. For instance, someone could argue that the election of 1896 marks the beginning of an era of Republican dominance following McKinley’s triumph over William Jennings Bryan and the combined forces of the Democratic Party and the Populists (See “Cross of Gold” Speech). Republicans would control both houses of Congress and the presidency until the election of 1912. That being said, the gaps between the parties in Congress were quite narrow at times and the Democrats maintained enough support to influence congressional politics. Thus the characterization of this era remains somewhat uncertain.

The Progressive Era marks another period for which an argument can be made that party development did occur. The Progressives alternately tried to destroy or reform political parties and brought about major changes to party politics in the process (See “Party Government in the United States”):

- the introduction of civil service reform that weakened party control over patronage (the practice of awarding government jobs for political loyalty);

- the Australian ballot (also known as the secret ballot that allowed voters to select candidates without the parties knowing who they were voting for), which lessened party influence at the ballot box;

- the advent of primaries (having nominees elected by voters rather than chosen by convention), which diminished party control over the nomination process;

- proposals for the implementation of more direct types of voter participation in the democratic process through initiatives (allowing citizens to bypass their state legislatures placing proposed statutes on the ballot), referendums (a general vote by the electorate on a political question that has been referred to them), and recalls (a vote to remove an elected representative from office before then end of his or her term) (See “The New Nationalism”, Progressive Party Platform 1912, and Popular Government).

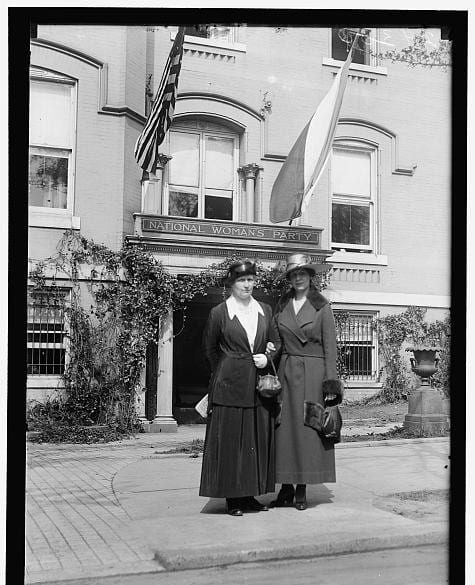

All these do not even take into account the constitutional amendments creating the direct election of senators and giving women the right to vote, both of which further altered the party system by giving the people direct control over senators and having women double the size of the electorate forcing the party system to reorganize to take into account this massive influx of new voters.

Another political era agreed on by many party scholars is the election of 1932 and the rise of Franklin Roosevelt. Roosevelt’s willingness to take on the role of party leader gave him powerful influence in Congress and allowed him to advance a programmatic agenda for the nation. The new Democratic coalition would prove a stable force for Roosevelt to build his programs and carry them into practice. That being said, Roosevelt’s efforts at building a modern state and centering national leadership in the presidency had the effect of displacing parties as agents of popular rule (See Acceptance Speech and Fireside Chat on Primaries). In short, the New Deal state took over for many party responsibilities and weakened political parties as a consequence. Combined with the Progressive reforms of the earlier era, parties exited the New Deal Era considerably weaker, mere shadows of their former selves.

A final era that could be defined in party development is Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980. Reagan, in this view, represents the culmination of conservative social movement politics that had its origins as far back as the 1960s (See Acceptance Speech). A programmatic Republican Party was replaced with the politics of ideology, and Reagan was able to sell conservatism to the American public with his charisma and optimism (See First Inaugural Address). Since that time the Republicans have been a party of ideology that puts loyalty to ideas ahead of compromise and conciliation. Moreover, there is some evidence that the Democratic Party has followed suit and become more ideological as well. Whether party politics are well served from being influenced by ideology is still being worked out in American politics today.

What is clear is that political parties in the twenty-first century bear a scant resemblance to their predecessors in the eighteenth, nineteenth, or twentieth centuries, and the chances of returning to an earlier era of party governance seems remote. Yet contemporary problems like voter alienation, low voter participation rates, government gridlock, and low popular trust in government may all have their roots in the weakening of political parties. Parties have traditionally been laboratories where people develop the habits of associating with others, the techniques of accommodation, and attachment to government institutions. What parties need is a sense of public purpose, but it is unlikely that this purpose is going to come from the parties themselves. Instead, the parties need strong leadership that can infuse public purpose into the parties and lead them to restored prominence and relevance in American politics. American parties are far from perfect, but they may be needed now more than ever to restore American politics from the twin dangers of cynicism and indifference. Given the traditional roles of parties, we must think seriously about whether a rejuvenation of the parties might be an elixir for our contemporary ills.

[1] James Ceaser, Presidential Selection (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979), 131–149.

The Case against Parties and Party Development

- James Madison, Federalist 10, November 22, 1787

- James Madison, “Parties, January 23, 1792

- James Madison, “A Candid State of Parties,” September 22, 1792

- Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Philip Mazzei, April 24, 1796

- President George Washington, Letter to Thomas Jefferson, July 6, 1796

- President George Washington, Farewell Address, September 19, 1796

- President Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801

Parties and Managing the Electorate

- Martin Van Buren, Letter to Thomas Ritchie, January 13, 1827

- Martin Van Buren, Autobiography, 1854

- Abraham Lincoln, “House Divided” Speech,” June 16, 1858

- Abraham Lincoln, Letter to Henry Pierce and Others, April 6, 1859

- Republican Party Platform 1860, May 17, 1860

- Democratic Party Platform 1860 (Douglas Faction), June 18, 1860

- Democratic Party Platform 1860 (Breckinridge Faction), November 6, 1860

Third Parties and the Structural Change in Parties

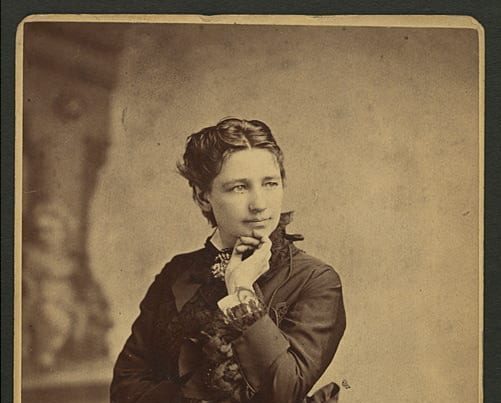

- Victoria Woodhull, “The Coming Woman,” April 2, 1870

- Woodrow Wilson, “Wanted— A Party,” September 1, 1886

- Populist Party Platform 1892, July 4, 1892

- William Jennings Bryan, “Cross of Gold” Speech, July 9, 1896

- Robert La Follette, “Peril in the Machine,” February 23, 1897

- George Washington Plunkitt, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall, 1905

- Woodrow Wilson, “Party Government in the United States,” 1908

- Theodore Roosevelt, “The New Nationalism,” September 1, 1910

- Progressive Party Platform 1912, November 5, 1912

- William Howard Taft, Popular Government, 1913

- National Woman’s Party Platform 1916, June 1916

- Progressive Party Platform 1924, November 4, 1924

Democratization of Parties

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Acceptance Speech, July 2, 1932

- President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Fireside Chat on Primaries, June 24, 1938

- Platform of the States Rights Democratic Party, August 14, 1948

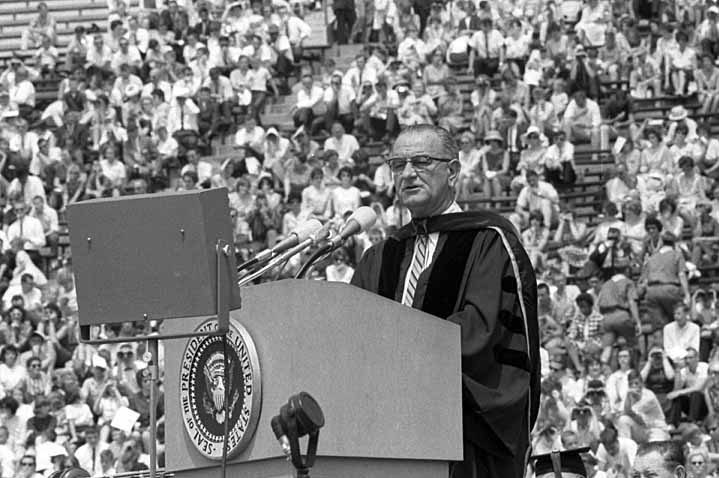

- President Lyndon B. Johnson, “Great Society” Speech, May 22, 1964

- Barry Goldwater, Acceptance Speech, July 16, 1964

- George Wallace, “Speech at Madison Square Garden,” October 24, 1968

- McGovern-Fraser Commission Report, September 22, 1971

- President Ronald Reagan, First Inaugural Address, January 20, 1981

- Republican Contract with America, September 27, 1994

- Green Party Platform 2000, June 25, 2000

- Price-Herman Commission Report, December 10, 2005

- Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, January 21, 2010

For each of the documents in this collection, we suggest questions relevant for that document alone (questions A) and questions that require comparison between documents (questions B).

1. Publius, Federalist 10 (November 22, 1787)

A. Why does Publius equate political parties with factions? Are parties and factions really the same thing according to Publius’ definition?

B. Compare what Publius says in Federalist 10 to Madison’s statements on parties (See “Parties” and “A Candid State of Parties”). How can Madison’s change in tone about parties be explained?

2. James Madison, “Parties” (January 23, 1792)

A. What does Madison mean when he distinguishes natural from artificial parties?

B. Is Madison speaking here as an impartial observer of the party system or as a partisan who is loyal to his political party? (See also “A Candid State of Parties”)

3. James Madison, “A Candid State of Parties” (September 22, 1792)

A. How does Madison describe the difference between the parties in his essay? Is this a fair comparison?

B. Is Madison’s view on parties analogous to Van Buren’s?

4. Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Philip Mazzei (April 24, 1796)

A. How does Jefferson’s letter to Mazzei reflect growing partisan discontent in the nation?

B. Does this growing discontent reflect a natural tendency for nations to break up into parties as Madison suggests?

5. President George Washington, Letter to Thomas Jefferson (July 6, 1796)

A. What does it say about Washington and the type of politician he was that he refused to acknowledge Jefferson’s letter?

B. Is Washington’s refusal to engage in partisan attacks reminiscent of the kind of representative Madison had in mind in Federalist 10? Is it possible to count on such representatives to always being in charge?

6. President George Washington, Farewell Address (September 19, 1796)

A. What fears does Washington express for the young nation about the dangers posed by parties?

B. Are Washington’s fears addressed by Jefferson in trying to bring unity to the political parties?

7. President Thomas Jefferson, First Inaugural Address (March 4, 1801)

A. What does Jefferson mean when he says, “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists”?

B. Is Jefferson’s statement easily reconciled with the kind of party characterization described by Madison?

8. Martin Van Buren, Letter to Thomas Ritchie (January 13, 1827)

A. Why does Van Buren address this letter to Thomas Ritchie? What did he hope to gain from winning Ritchie’s confidence?

B. Given Van Buren’s view of parties, is it fair to say that he was responsible for building the modern Democratic Party?

9. Martin Van Buren, Autobiography (1920)

A. Why does Van Buren believe that parties are inseparable from free government?

B. Why does Van Buren have such a different view of political parties than Washington?

10. Abraham Lincoln, “House Divided” Speech”(June 16, 1858)

A. What did Lincoln mean when he said “a house divided against itself cannot stand”?

B. Was Lincoln trying for some sort of statement of unity much like Jefferson did in 1801?

11. Abraham Lincoln, Letter to Henry Pierce and Others (April 6, 1859)

A. Why did Lincoln believe that the Declaration of Independence forms a common ground for political discourse?

B. Is the breakup of the Democratic Party (See (Northern) Democratic Party Platform and (Southern) Democratic Party Platform) exactly the kind of event that Lincoln was warning about in his letter?

12. Republican Party Platform 1860 (May 17, 1860)

A. How do the Republicans try to frame the issues of 1860? How do they try to temper their abolitionist wing?

B. How does the platform compare with the ideas from Lincoln’s “House Divided” Speech?

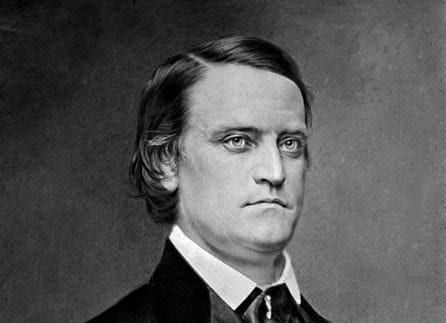

13. Democratic Party Platform 1860 (Douglas Faction) (June 18, 1860)

A. How does the Douglas faction of the Democratic Party try to navigate the slavery issue in their platform?

B. How does the Douglas faction differ from the Breckinridge faction in terms of the platform stance?

14. Democratic Party Platform 1860 (Breckinridge Faction) (November 6, 1860)

A. Why does the Breckinridge faction of the Democratic Party take the position on slavery that it does?

B. Does the Breckinridge platform represent a rejection of the Declaration of Independence (See Letter to Henry Pierce and Others)?

15. Victoria Woodhull, Announcement (March 29, 1870)

A. Where does Woodhull stand on the major issues of the day?

B. Is Woodhull right to focus on more issues than just women’s suffrage ( See Platform of the National Women’s Party)?

16. Woodrow Wilson, “Wanted—A Party” (September 1, 1886)

A. How did Woodrow Wilson believe that parties could be made stronger?

B. Do Wilson’s ideas have merit given the state of the big city machines (See Plunkitt of Tammany Hall)?

17. Populist Party Platform 1892 (July 4, 1892)

A. Based on their platform, how would you explain the popularity of the populists in 1892? What were they tapping into about American culture at the time?

B. What are some of the essential differences between the populists and the progressives (See Progressive Party Platform 1912 and Progressive Party Platform of 1924)?

18. William Jennings Bryan, “Cross of Gold” Speech (July 9, 1896)

A. If Bryan’s speech and his campaign were so popular, why did he lose to McKinley? What does that tell us about the state of American politics at the time?

B. How well did Bryan’s speech merge with populist ideas?

19. Robert La Follette, “Peril in the Machine” (February 23, 1897)

A. Why does La Follette believe that parties fall apart into machines? What is the remedy for machine politics?

B. Does La Follette propose remedies that could address the likes of George Washington Plunkitt?

20. George Washington Plunkitt, Plunkitt of Tammany Hall (1905)

A. What does George Washington Plunkitt mean by “honest graft”? If this is how big city machines operated in practice, did they deserve to be called corrupt?

B. Do the big city machines give rise to the need for Roosevelt’s New Nationalism?

21. Woodrow Wilson, “Party Government in the United States” (1908)

A. Why did Woodrow Wilson want to reform political parties when so many other Progressives wanted to try to abolish them?

B. How do Wilson’s views differ from the Progressive Party Platform of 1912?

22. Theodore Roosevelt, “The New Nationalism” (September 1, 1910)

A. What was the New Nationalism and how did it propose to transform American politics?

B. How does the New Nationalism compare with Taft’s Popular Government?

23. Progressive Party Platform 1912, (November 5, 1912)

A. How do the Progressives differentiate themselves from the major parties in 1912?

B. What are some major differences between the Progressive Party Platform of 1912 and the Progressive Party Platform of 1924?

24. William Howard Taft, Popular Government (1913)

A. Why does Taft oppose direct popular primaries? Do his objections have any merit?

B. How does Taft compare with Roosevelt’s New Nationalism speech on the role of progressive reforms?

25. National Woman’s Party Platform 1916 (June 1916)

A. Why does the National Woman’s Party choose to focus on only one issue in their platform?

B. Should the National Woman’s Party have been more encompassing like the Progressives in 1912 or 1924?

26. Progressive Party Platform 1924 (November 4, 1924)

A. What are some key features of the Progressive Party Platform of 1924?

B. What differentiates the Progressive Party Platform of 1924 from the Progressive Party Platform of 1912?

27. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Acceptance Speech”(July 2, 1932)

A. Roosevelt promises a “new deal” for the American people in the speech. What does he mean by this?

B. Is Roosevelt’s New Deal a fulfillment of Theodore Roosevelt’s New Nationalism?

28. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Fireside Chat on Primaries (June 24, 1938)

A. Why is it important to Roosevelt that all voters participate in presidential primaries?

B. Is Roosevelt’s fireside chat a precursor to the McGovern-Fraser Commission?

29. Platform of the States Rights Democratic Party, August 14, 1948

A. Why does the States Rights Democratic Party believe that the pursuit of civil rights is so destructive to the American republic?

B. Does the States Rights Democratic Party have anything in common with the Breckinridge faction of the Democratic Party from 1860?

30. President Lyndon B. Johnson, “Great Society” Speech (May 22, 1964)

A. What is the Great Society and how can it be seen as an extension of the New Deal?

B. Would FDR have agreed with the direction and scope of Johnson’s Great Society?

31. Barry Goldwater, Acceptance Speech”(July 16, 1964)

A. How can Goldwater be understood as a reaction to modern liberalism (i.e., regulated markets and the use of government to expand civil and political rights) ushered in by FDR?

B. What distinguishes Goldwater from Wallace as a reactionary against the Great Society?

32. George Wallace, “Speech at Madison Square Garden” (October 24, 1968)

A. Why does Wallace focus on the need to preserve law and order in America as one of the main points in this speech?

B. Does the States Rights Democratic Party anticipate the candidacy of George Wallace in 1968?

33. McGovern-Fraser Commission Report (September 22, 1971)

A. What reforms are proposed by the McGovern-Fraser Commission Report to correct perceived defects in the nomination process? Does the shift to primaries really produce better nominees than conventions? Have these reforms worked?

B. Does the McGovern-Fraser Commission bring to fulfillment the goal of the Progressives?

34. President Ronald Reagan, First Inaugural Address (January 20, 1981)

A. What is the basis of the new conservatism that Reagan brought to American politics with his election?

B. In what ways does Reagan build on the earlier work of Barry Goldwater? Can Reagan’s views be seen as an extension of Goldwater’s ideas? What new elements does Reagan bring to his articulation of conservatism?

35. Republican Contract with America (September 27, 1994)

A. Do the Republicans present a clear and compelling political agenda?

B. How might we compare the Contract with America with the other party platforms (See Republican Party Platform 1860, (Northern) Democratic Party Platform, (Southern) Democratic Party Platform, Populist Party Platform, Progressive Party Platform 1912, Platform of the National Women’s Party, Progressive Party Platform of 1924, and Platform of the States Rights Democratic Party)?

36. Green Party Platform 2000 (June 25, 2000)

A. How do the Greens differentiate themselves from the major political parties?

B. How do the Greens compare with other third-party movements in American history (See Progressive Party Platform 1912, Platform of the National Women’s Party, Progressive Party Platform of 1924, and Platform of the States Rights Democratic Party)?

37. Price-Herman Commission Report (December 10, 2005)

A. What is the problem with states moving primaries earlier and earlier in the primary process?

B. Does the Price-Herman Commission Report enhance earlier reform efforts with the nominating process (See McGovern-Fraser Commission Report)?

38. Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (January 21, 2010)

A. Why does the Supreme Court hold that corporations deserve First Amendment protection?

B. How does this ruling compare with the goals of direct democracy and government accountability favored by the Progressives?

Ceaser, James, Presidential Selection (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979).

Gerring, John, Party Ideologies in America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

Gould, Lewis L., Grand Old Party (New York: Random House, 2003).

Kazin, Michael, The Populist Persuasion: An American History (New York: Basic Books, 1995).