Introduction

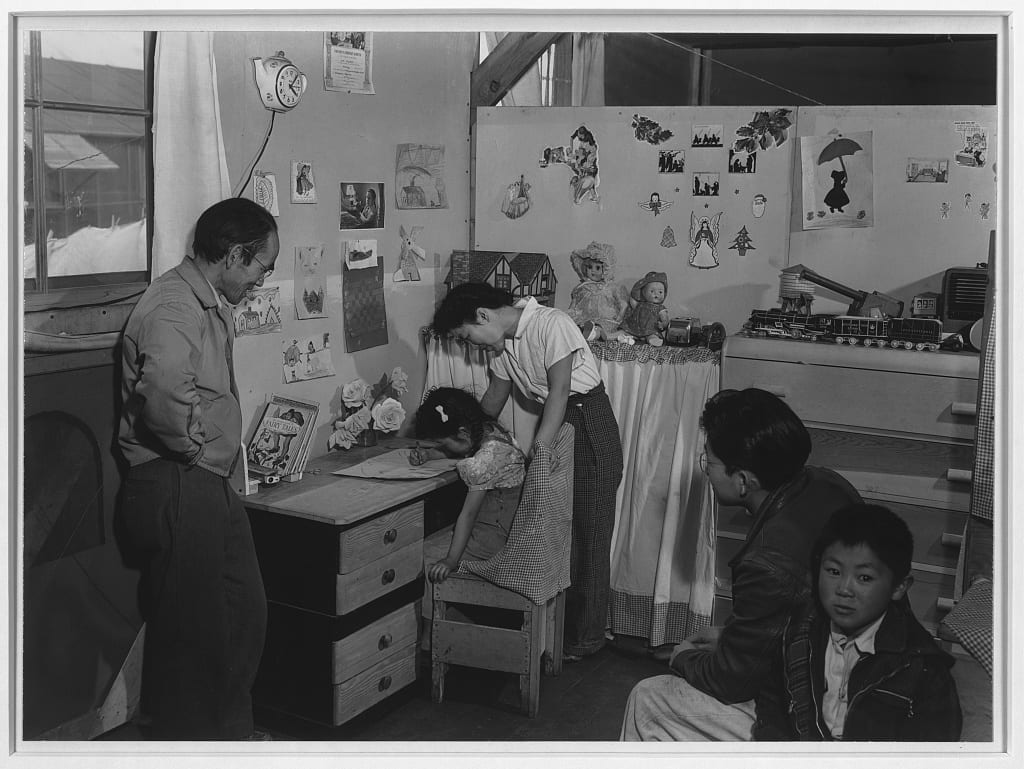

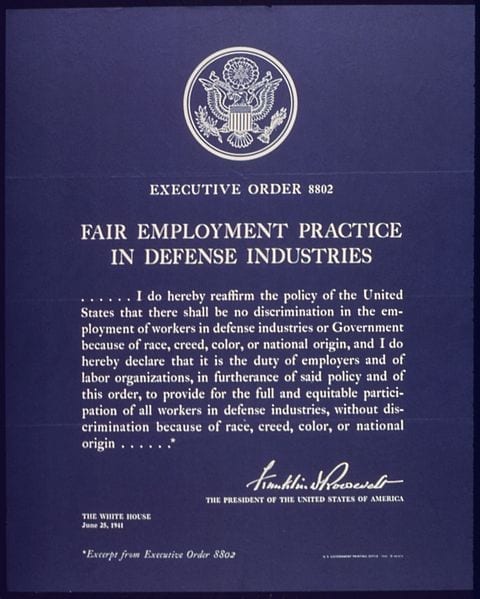

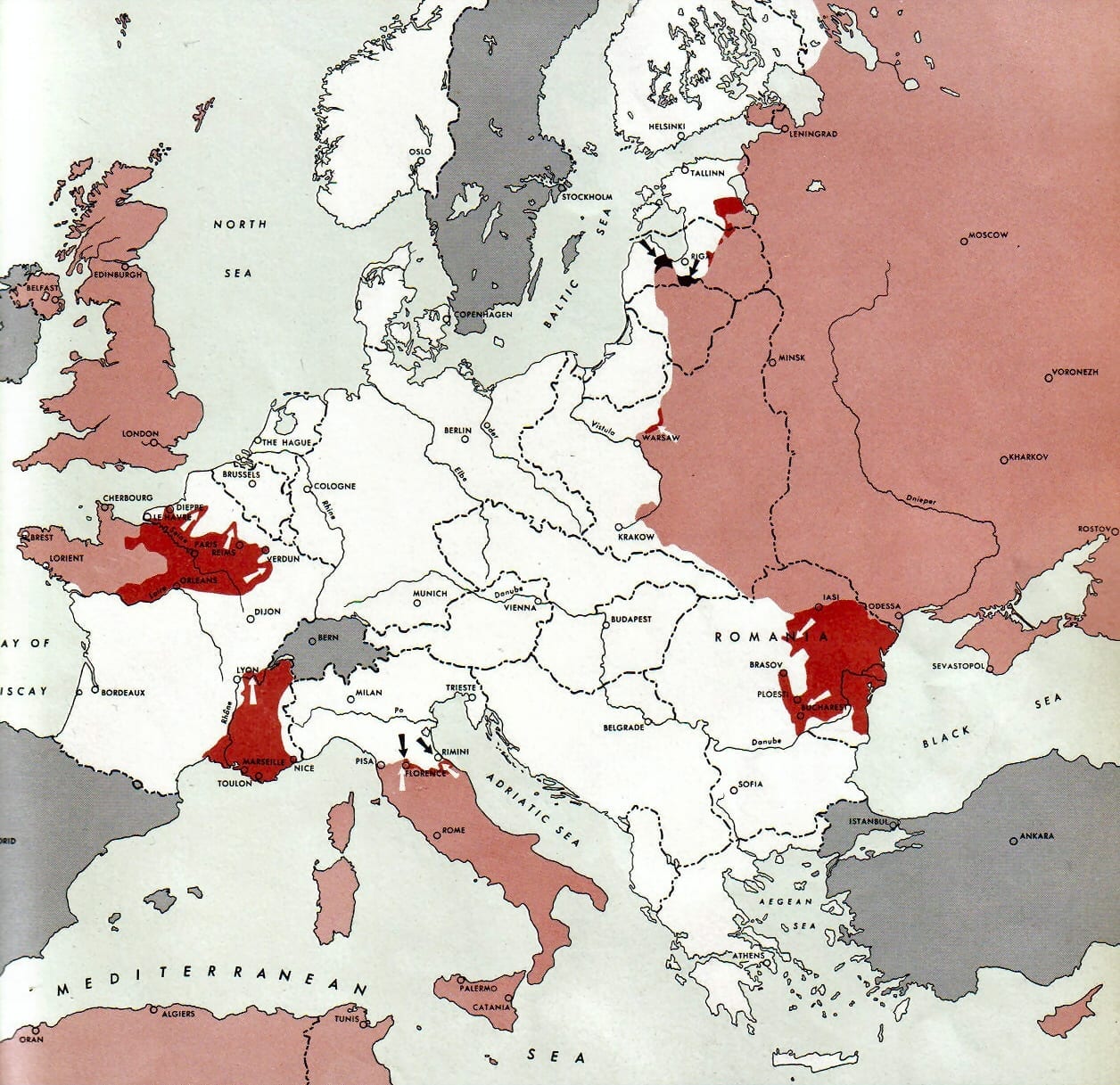

Rupert Trimmingham’s letters to Yank, a weekly magazine published by the U.S. military, laid bare the daily affronts that black soldiers encountered while serving their country in World War II. Nearly one million African Americans served in uniform during the war. The willingness of Yank, an offical publication, to publish his letter revealed the overall importance of black soldiers and workers to the war effort. Maintaining black morale required openly acknowledging that racial prejudice was a problem that existed. The double-victory campaign within the civil rights movement emphasized defeating facism abroad and racial discrimination at home.

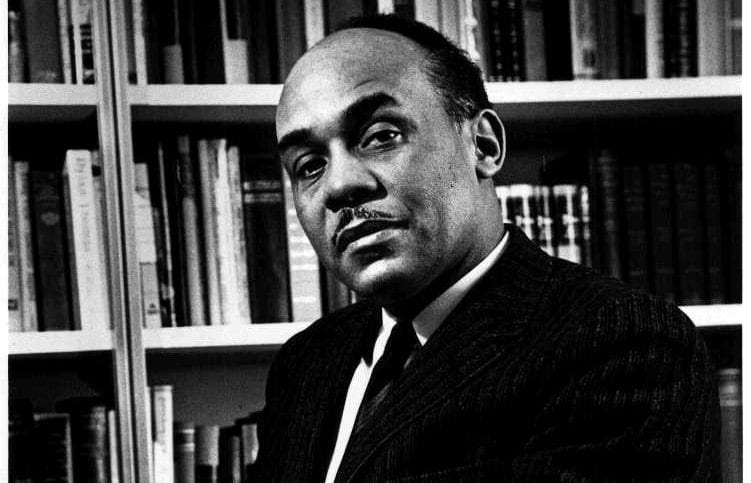

—Jennifer D. Keene

Source: Rupert Trimmingham, letters to the editor, Yank, April 28, 1944 and July 28, 1944.

April 28, 1944

Dear Yank,

Here is a question that each Negro soldier is asking. What is the Negro soldier fighting for? On whose team are we playing? Myself and eight other soldiers were on our way from Camp Claiborne, La., to the hospital here at Fort Huachuca. We had to lay over until the next day for our train. On the next day we could not purchase a cup of coffee at any of the lunchrooms around there. As you know, Old Man Jim Crow rules. The only place where we could be served was at the lunchroom at the railroad station but, of course we had to go into the kitchen. But that’s not all; 11:30 a.m. about a two dozen German prisoners of war, with two American guards, came into the station. They entered the lunchroom, sat at the tables, had their meals served, talked, smoked, in fact had quite a swell time. I stood on the outside looking on, and I could not help but ask myself these questions: Are these men sworn enemies of this country? Are they not taught to hate and destroy all democratic governments? Are we not American soldiers, sworn to fight for and die if need be for this country? Then why are they treated better than we are? Why are we pushed around like cattle? If we are fighting for the same thing, if we are to die for our country, then why does the Government allow such things to go on? Some of the boys are saying that you will not print this letter. I’m saying that you will.

Cpl. Rupert Trimmingham

Fort Huachuca, Ariz.

July 28, 1944

Dear Yank,

Allow me to thank you for publishing my letter. Although there was some doubt about its being published, yet somehow I felt that Yank was too great a paper not to. . . . Each day brings three, four or five letters to me in answer to my letter. I just returned from furlough and found 25 letters awaiting me. To date I’ve received 287 letters, and, strange as it may seem, 183 are from white men and women in the armed service. Another strange feature about these letters is that most of these people are from the Deep South. They are all proud of the fact that they are of the South but ashamed to learn that there are so many of their own people who by their actions and manner toward the Negro are playing Hitler’s game. Nevertheless, it gives me new hope to realize that there are doubtless thousands of whites who are willing to fight this Frankenstein that so many white people are keeping alive. All that the Negro is asking for is to be given half a chance and he will soon demonstrate his worth to his country. Should these white people who realize that the Negro is a man who is loyal – one who would gladly give his life for this our wonderful country – would stand up, join with us and help us to prove to their white friends that we are worthy, I’m sure that we would bury race hate and unfair treatment. Thanks again.

Cpl. Rupert Trimmingham

Fort Huachuca, Ariz.