Introduction

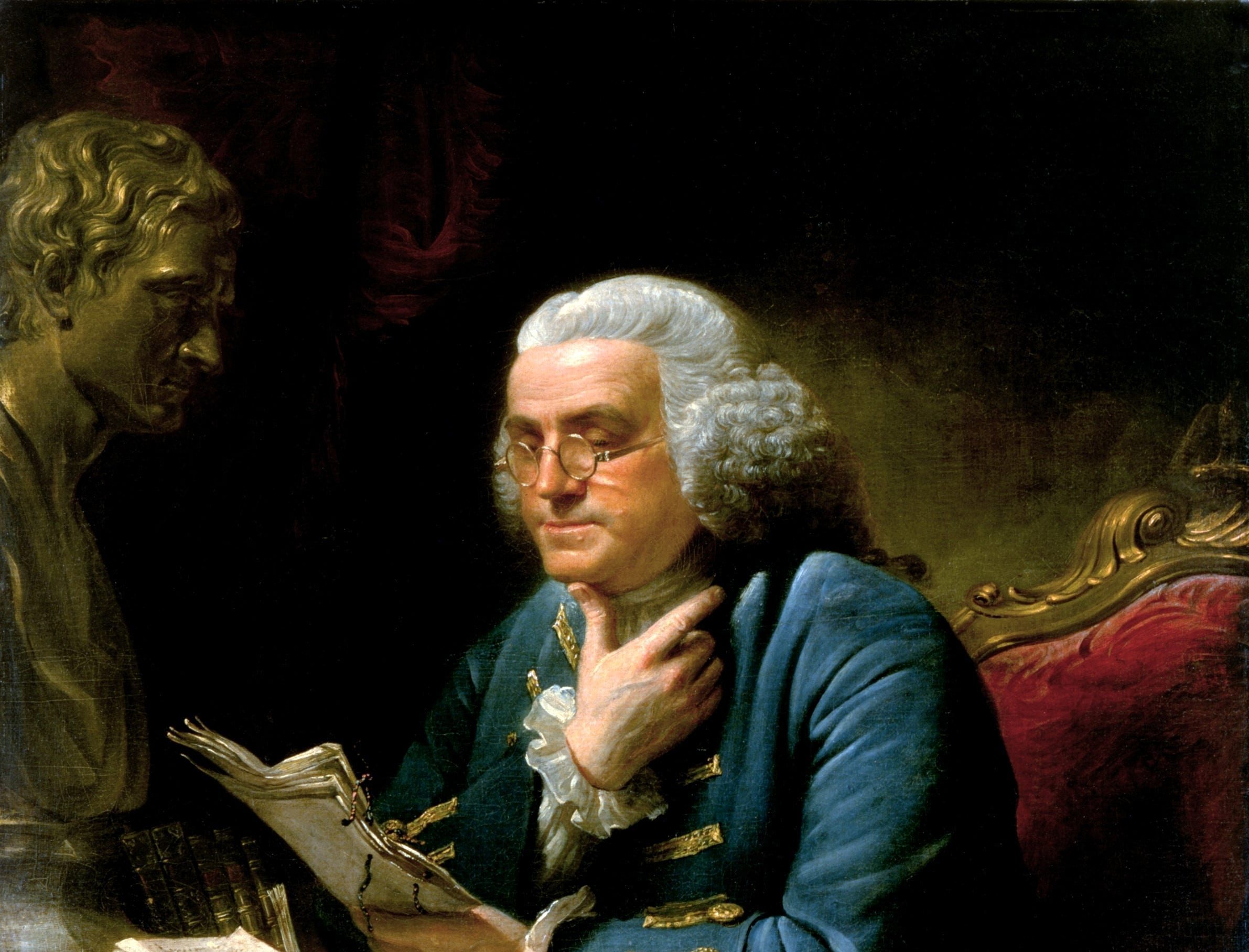

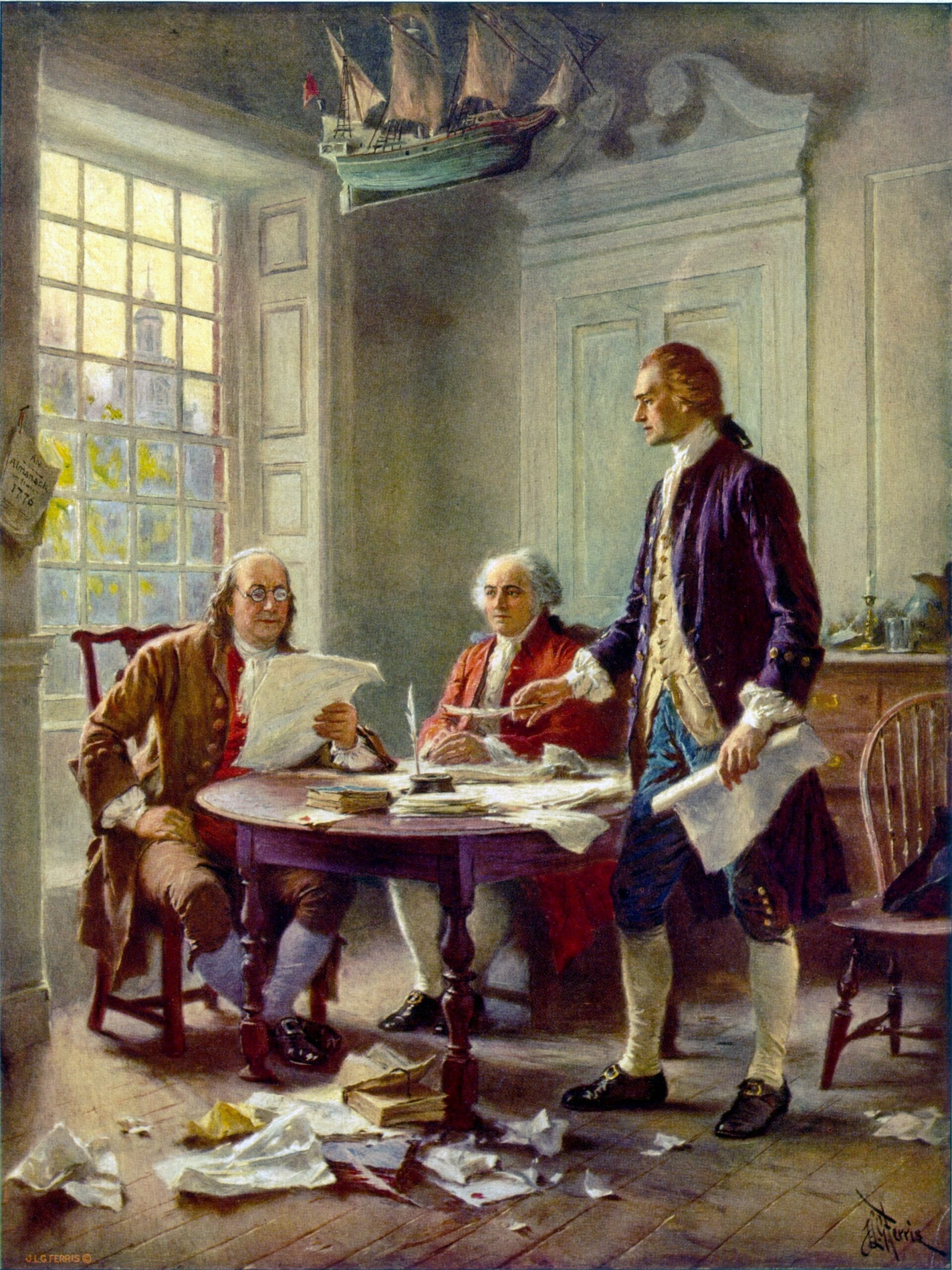

At the conclusion of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, a woman reportedly asked Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) whether the United States would have a monarchy or a republic. “A republic,” he replied, but only “if you can keep it.”

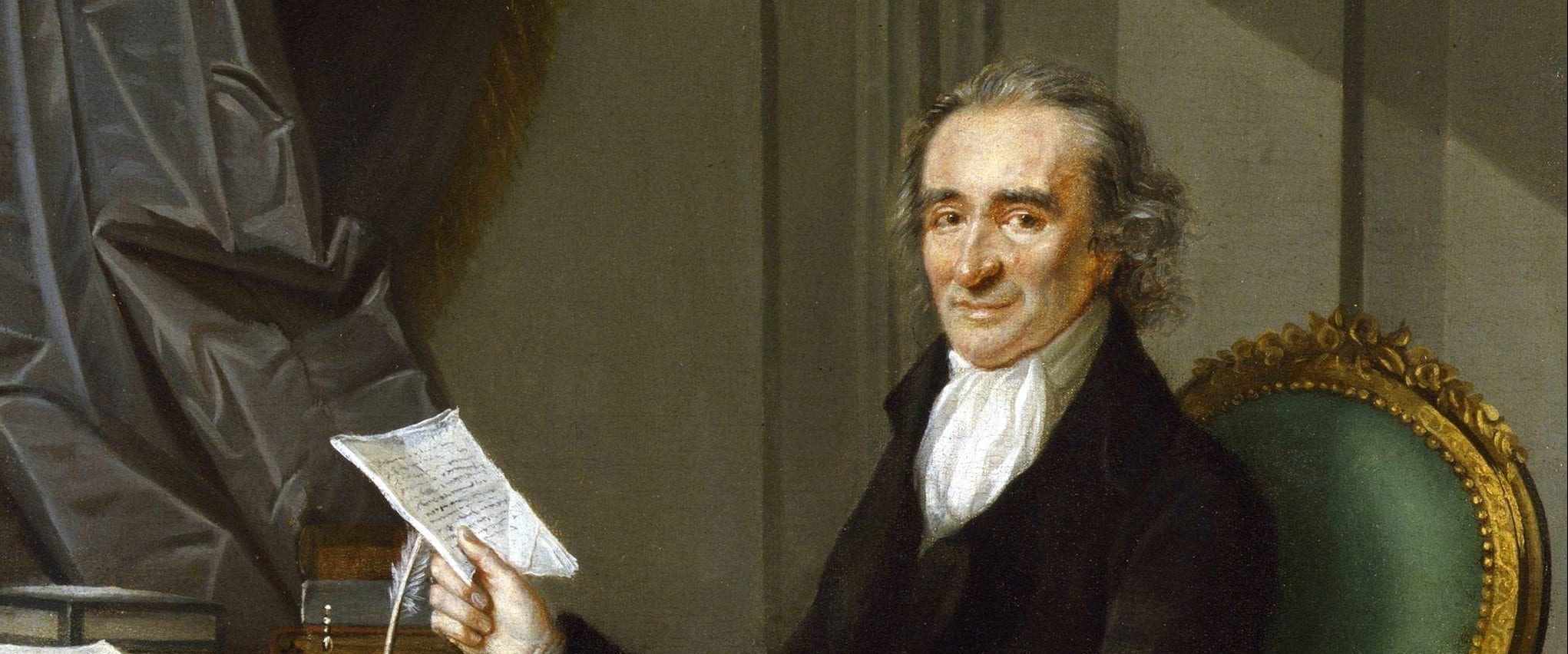

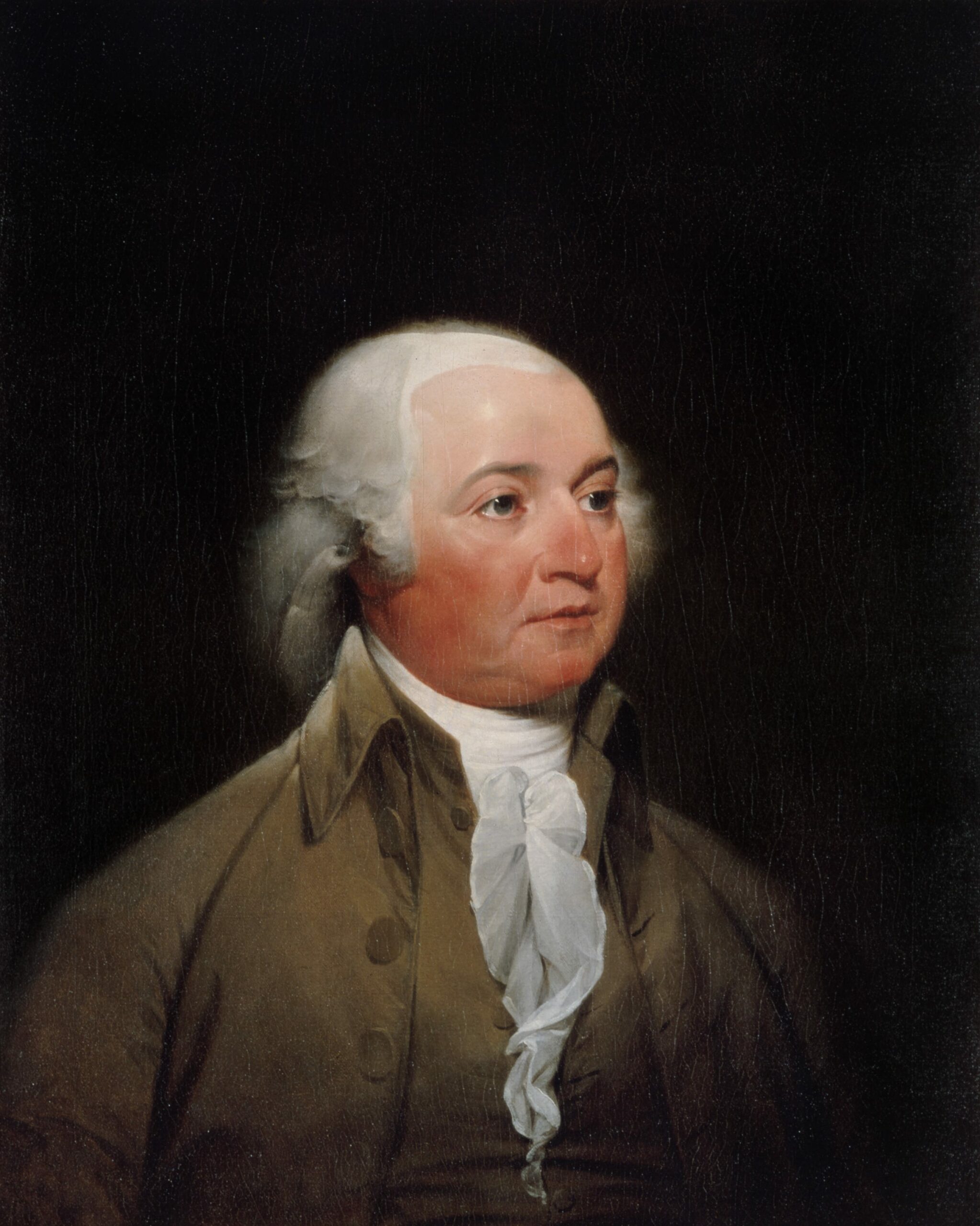

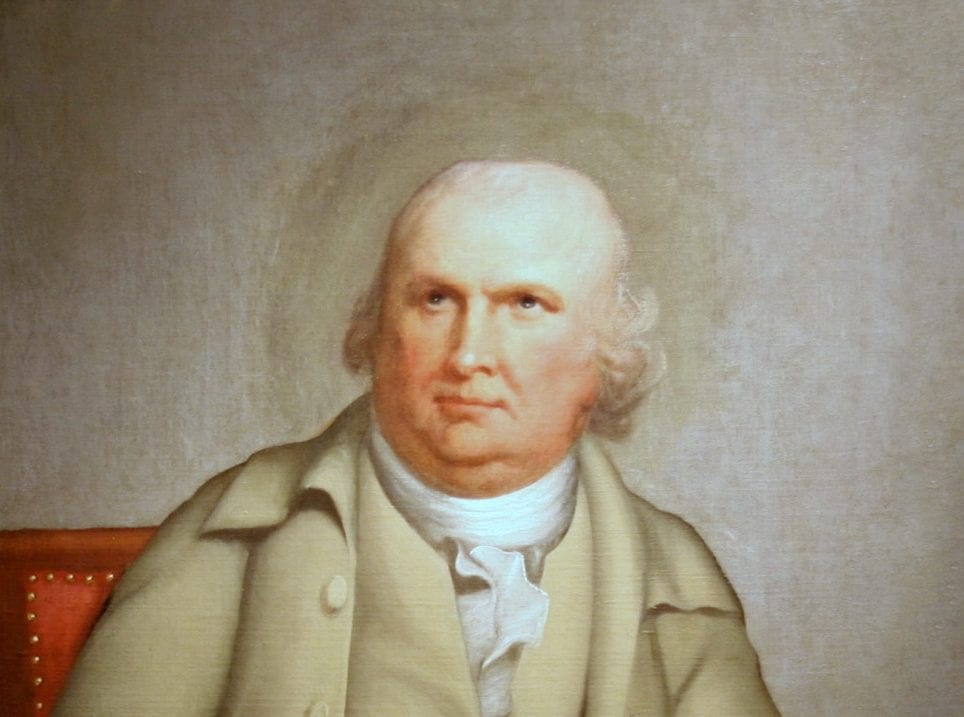

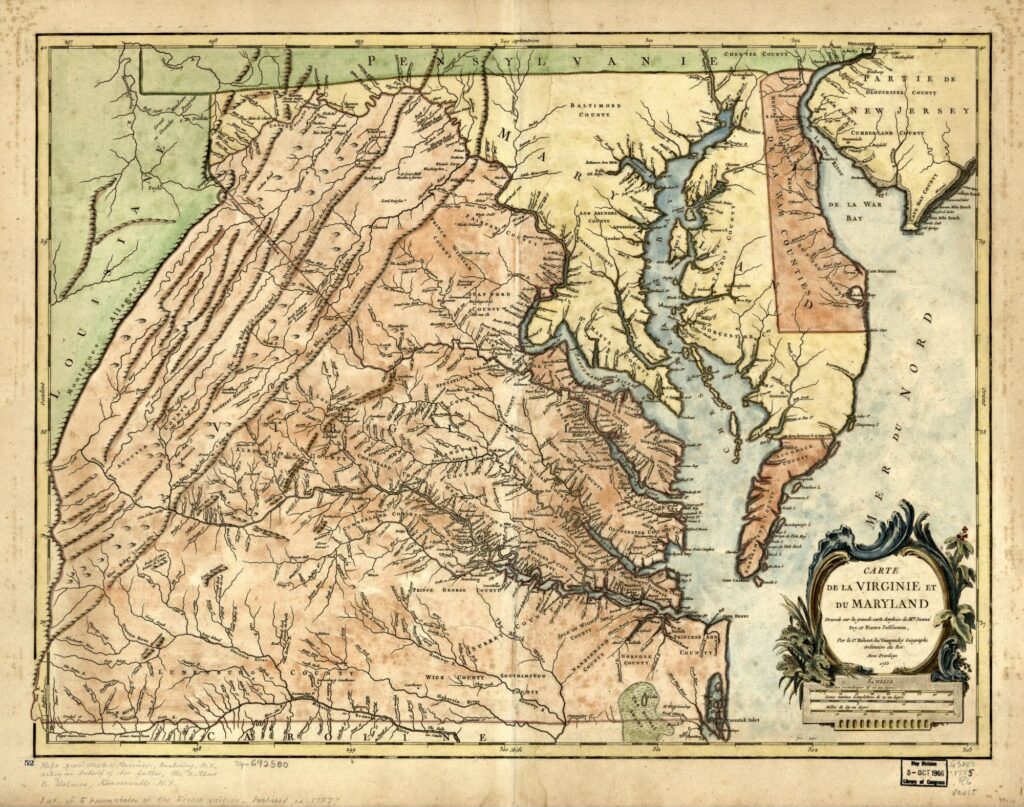

Franklin’s belief that the liberty of the American people hinged not only on their form of government but also on their character was shared by Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), who between 1781 and 1784 wrote and revised a book, privately printed in 1785 and published in 1787, titled Notes on the State of Virginia. Inspired by a series of questions posed by a French diplomat, Jefferson’s Notes considered everything from agriculture to zoology. What he wrote in response to queries regarding Virginia’s culture and economy helps to capture his mixed feelings about the ability of Virginians and other Americans to successfully carry out their experiment in self-government.

In “Manners” (Query XVIII), Jefferson considered the ways in which the institution of slavery harmed the enslaved as well as their masters. He had seen firsthand the obvious injustices that slavery inflicted on African Americans. He also perceived its ill effects on the work ethic and capacity for citizenship of white people. One of his first public acts had been to sponsor a 1769 measure, rejected by the Virginia House of Burgesses, to make it legal for masters to emancipate their slaves. In 1778 he succeeded in banning the importation of enslaved Africans to Virginia. In 1779, however, his proposal for gradual emancipation in his state failed to win support. Complicating his opposition to slavery was his worry, expressed in Query XVIII, that African Americans would have difficulty forgiving those who had once exploited them, as well as his suspicion, recorded elsewhere in his Notes, that former slaves could never rise to the level of their former masters.

If slavery caused Jefferson to fear America’s future, he found reasons for hope in his section on “Manufactures” (Query XIX). Unlike in Europe, where a scarcity of land forced the populace into positions of dependence as urban wage laborers, America remained a nation composed largely of farmers who owned their own land and worked as their own bosses. Therefore they enjoyed an independence of mind and means, making possible their participation in politics as virtuous citizens seeking the common good instead of selfish gain.

Source: Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (London: John Stockdale, 1787), 270–75. https://archive.org/details/notesonstateofvi1787jeff/page/270

Query 18: The particular customs and manners that may happen to be received in that state?

It is difficult to determine on the standard by which the manners of a nation may be tried, whether catholic, or particular. It is more difficult for a native to bring to that standard the manners of his own nation, familiarized to him by habit. There must doubtless be an unhappy influence on the manners of our people produced by the existence of slavery among us. The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do. If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love, for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present. But generally it is not sufficient. The parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments[1] of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to his worst of passions, and thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities. The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances. And with what execration[2] should the statesman be loaded, who permitting one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies, destroys the morals of the one part, and the amor patriae[3] of the other. For if a slave can have a country in this world, it must be any other in preference to that in which he is born to live and labor for another: in which he must lock up the faculties of his nature, contribute as far as depends on his individual endeavors to the evanishment[4] of the human race, or entail[5] his own miserable condition on the endless generations proceeding from him. With the morals of the people, their industry also is destroyed. For in a warm climate, no man will labor for himself who can make another labor for him. This is so true, that of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed are ever seen to labor. And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever: that considering numbers, nature, and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation, is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest. But it is impossible to be temperate and to pursue this subject through the various considerations of policy, of morals, of history natural and civil. We must be contented to hope they will force their way into everyone’s mind. I think a change already perceptible, since the origin of the present revolution. The spirit of the master is abating, that of the slave rising from the dust, his condition mollifying, the way I hope preparing, under the auspices of heaven, for a total emancipation, and that this is disposed, in the order of events, to be with the consent of the masters, rather than by their extirpation.[6]

Query 19: The present state of manufactures, commerce, interior and exterior trade?

We never had an interior trade of any importance. Our exterior commerce has suffered very much from the beginning of the present contest. During this time we have manufactured within our families the most necessary articles of clothing. Those of cotton will bear some comparison with the same kinds of manufacture in Europe; but those of wool, flax, and hemp are very coarse, unsightly, and unpleasant; and such is our attachment to agriculture, and such our preference for foreign manufactures, that be it wise or unwise, our people will certainly return as soon as they can, to the raising of raw materials, and exchanging them for finer manufactures than they are able to execute themselves.

The political economists of Europe have established it as a principle that every state should endeavor to manufacture for itself; and this principle, like many others, we transfer to America, without calculating the difference of circumstance which should often produce a difference of result. In Europe the lands are either cultivated, or locked up against the cultivator. Manufacture must therefore be resorted to of necessity not of choice, to support the surplus of their people. But we have an immensity of land courting the industry of the husbandman. Is it best then that all our citizens should be employed in its improvement, or that one half should be called off from that to exercise manufactures and handicraft arts for the other? Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. It is the focus[7] in which he keeps alive that sacred fire, which otherwise might escape from the face of the earth. Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example. It is the mark set on those, who not looking up to heaven, to their own soil and industry, as does the husbandman, for their subsistence, depend for it on the casualties and caprice of customers. Dependence begets subservience and venality, suffocates the germ of virtue, and prepares fit tools for the designs of ambition. This, the natural progress and consequence of the arts, has sometimes perhaps been retarded by accidental circumstances: but, generally speaking, the proportion which the aggregate of the other classes of citizens bears in any state to that of its husbandmen, is the proportion of its unsound to its healthy parts, and is a good enough barometer whereby to measure its degree of corruption. While we have land to labor then, let us never wish to see our citizens occupied at a workbench, or twirling a distaff. Carpenters, masons, smiths, are wanting in husbandry; but, for the general operations of manufacture, let our workshops remain in Europe. It is better to carry provisions and materials to workmen there, than bring them to the provisions and materials, and with them their manners and principles. The loss by the transportation of commodities across the Atlantic will be made up in happiness and permanence of government. The mobs of great cities add just so much to the support of pure government, as sores do to the strength of the human body. It is the manners and spirit of a people which preserve a republic in vigor. A degeneracy in these is a canker[8] which soon eats to the heart of its laws and constitution.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.

Our Core Document Collection allows students to read history in the words of those who made it. Available in hard copy and for download.