Introduction

When the Virginia colony was founded in 1607, the majority of unfree laborers in the colony were indentured servants, men and women who signed a legal contract called an indenture that bound them to work for a certain individual for a certain number of years, in exchange for which they received room, board, and some type of education or training. During their indenture, the servant was legally subject to the rule of their master; although there were laws to protect servants, Virginia’s spread-out settlements meant that working conditions in actuality varied widely. No matter how oppressive their master, however, at the end of their indenture period, the individual servant was free to leave (usually with a set of supplies and a sum of money adequate for starting out on his or her own way in the world).

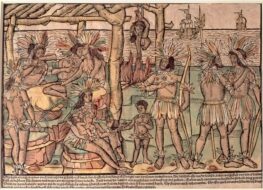

The second class of unfree labor consisted of slaves. At the beginning of the colonial period, records indicate that the most significant difference between slavery and indentured servitude lay in the expectation that, in the latter case, the individual would receive the sort of training and tools necessary to eventually take their place as a free person. In the early seventeenth century, race-based slavery for life did not exist in the Anglo-American world. Instead, where it existed, slavery was linked to the cultural and religious background of the enslaved person: non-Christian captives taken in a war, for example, might be enslaved, but not Christians, regardless of their racial or ethnic background. Nor was slavery always a permanent and inheritable condition: in the early years of the colony, individual slaves were able to win their freedom by demonstrating proof of their conversion to Christianity; in addition, enslaved persons were sometimes able to arrange to purchase their freedom, and policies regarding the status of children born to enslaved persons remained in flux until the mid-seventeenth century.

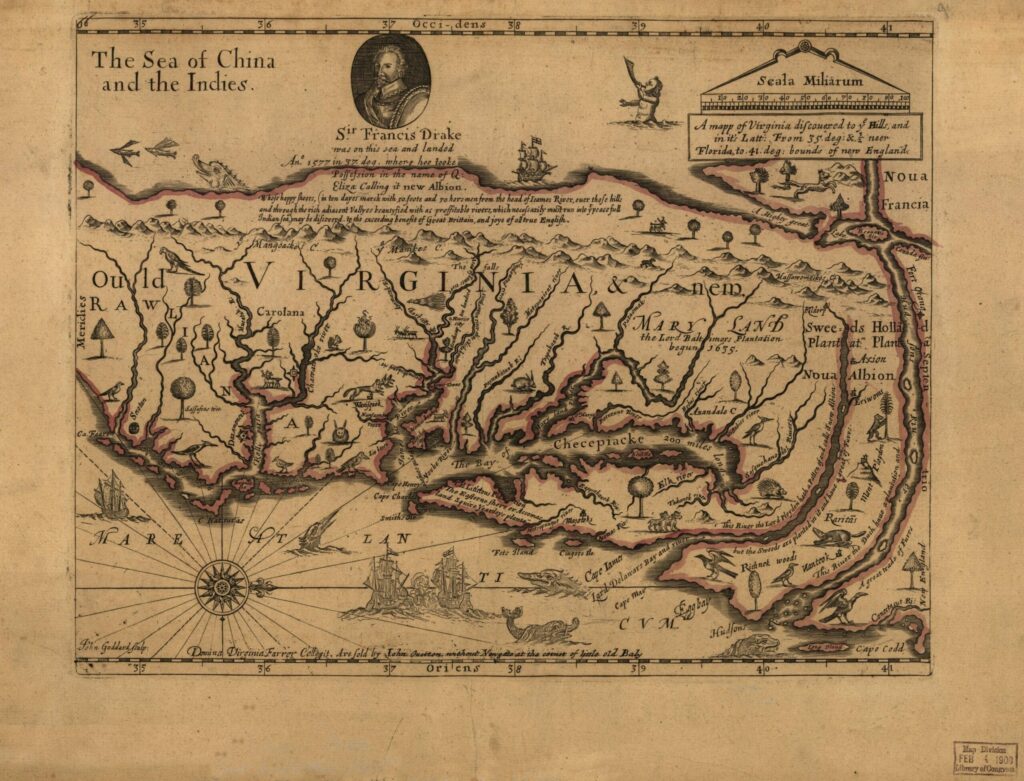

From the beginning, both forms of unfree labor coexisted in Virginia: the funders of the colony relied upon a mix of incentives (free land in exchange for a period of labor) and the bad economy in England to encourage laborers to come to the new colony as indentured servants, while the colonists took captives as slave hostages during their frequent conflicts with the local native population. The first slaves from Africa arrived at Jamestown in 1619.

Initially, the majority of the colony’s labor force consisted of indentured servants, but over time, as the English expanded their participation in the Atlantic and Indian slave trades and market conditions in the mother country improved, the balance shifted. By the end of the 1670s, black slaves began to replace both white indentured servants and Indian slaves as Virginians’ primary source of labor.

Susan Myra Kingsbury, ed., The Records of the Virginia Company of London (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1933), 4:58-60. Richard Frethorne, perhaps little more than a boy when he arrived, was an indentured servant in Virginia for two years before his death there in 1624.

Loving and kind father and mother, my most humble duty remembered to you, hoping in God of your good health. . . . This is to let you understand that I, your child, am in a most heavy case by reason of the nature of the country: [it] is such that it causes much sickness, as the scurvy and the bloody flux, and diverse other diseases, which makes the body very poor, and weak. [A]nd when we are sick there is nothing to comfort us; for since I came out of the ship, I never ate anything but peas, and loblollie [that is water gruel]; as for deer or venison, I never saw any since I came into this land. There is indeed some fowl, but we are not allowed to go and get it, but must work hard both early and late for a mess of water gruel, and a mouthful of bread, and beef. A mouthful of bread for a penny loaf must serve for four men which is most pitiful.

. . . We live in fear of the enemy. . . . [W]e have had a combat with them on the Sunday before Shrovetide [the beginning of Lent], and we took two alive, and made slaves of them, but it was by policy, for we are in great danger, for our plantation is very weak, by reason of the dearth, and sickness, of our company.

. . .

I have nothing to comfort me, nor there is nothing to be gotten here but sickness, and death, except that one had money to lay out in some things for profit; but I have nothing at all, no not a shirt to my back, but two rags, nor no clothes, but one poor suite, nor but one pair of shoes, but one pair of stockings, but one cap, but two band[s], my cloak is stolen by one of my own fellows, and to his dying however would not tell me what he did with it but some of my fellows saw him have butter and beef out of a ship, which my cloak I doubt [not?] paid for, so that I have not a penny, nor a penny worth to help me to either spice, or sugar, or strong waters, without the which one cannot live here, for as strong beer in England doth fatten and strengthen them so water here doth wash and weaken. . . .

I am not half a quarter so strong as I was in England, and all is for want of victuals, for I do protest unto you, that I have eaten more in day at home then I have allowed me here for a week. You have given more than my day’s allowance to a beggar at the door; and if Mr [John] Jackson had not relieved me, I should be in a poor case, but he like a father and she like a loving mother doth still help me. . . .

Goodman Jackson . . . much marveled that you would send me a servant to the Company.

He saith, I had been better knocked on the head, and indeed, so I find it now to my great grief and misery, and saith, that if you love me you will redeem me suddenly, for which I do entreat and beg. If you cannot get the merchants to redeem me for some little money, then for God’s sake, get a gathering or entreat some good folks to lay out some little sum of money, in meal and cheese and butter and beef, any eating meat will yield great profit. Oil and vinegar is very good, but father there is great loss in leaking, but for God’s sake send beef and cheese and butter, or the more of one sort and none of the other. . . . Look, whatsoever you send me, be it never so much, look what I make of it, I will deal truly with you. I will send it over, and beg the profit to redeem me, and if I die before it come, I have entreated Goodman Jackson to send you the worth of it, who hath promised he will. . . .

Good father do not forget me, but have mercy and pity my miserable case. I know if you did but see me you would weep to see me. . . .

Richard Frethorne

Martyns Hundred