Introduction

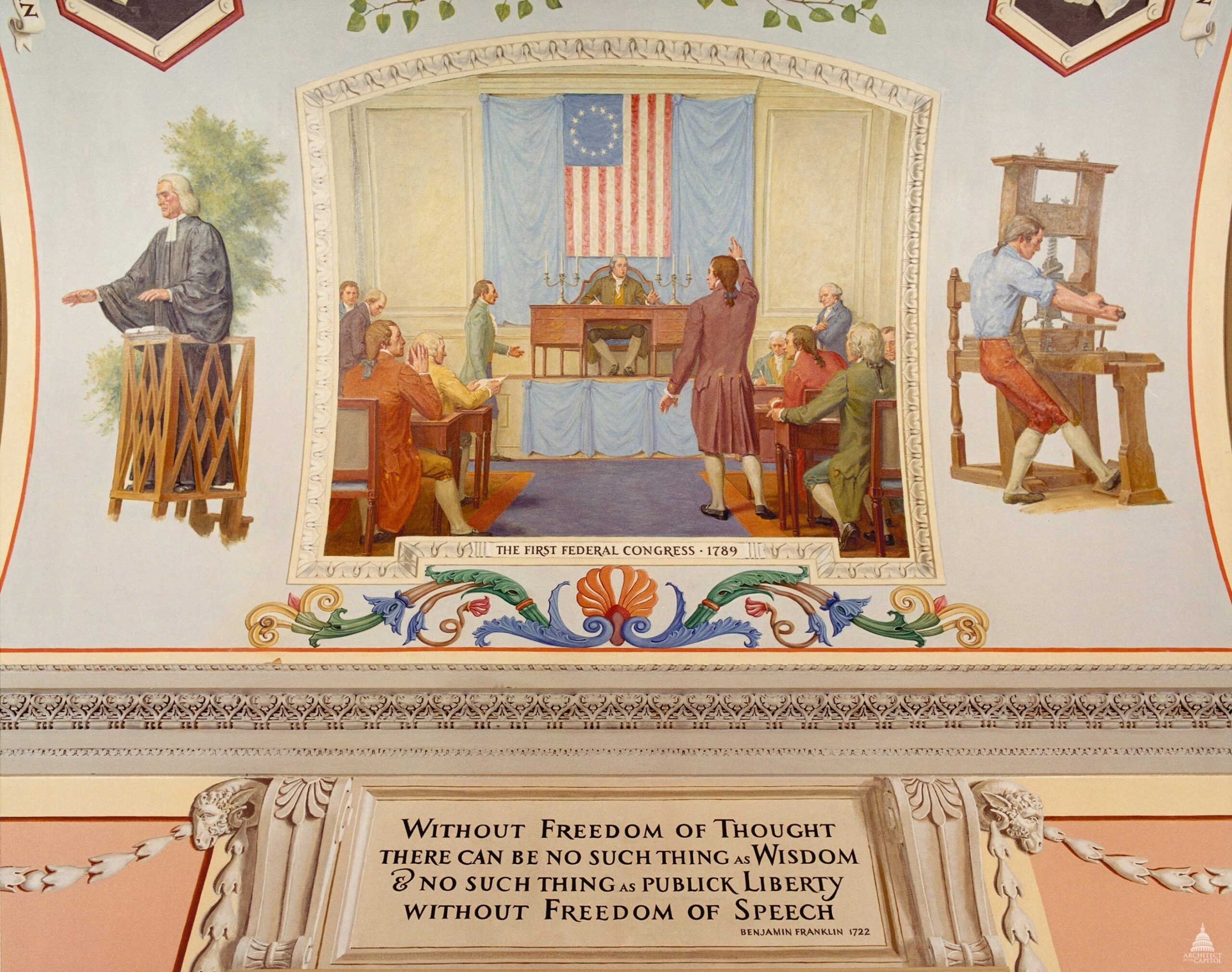

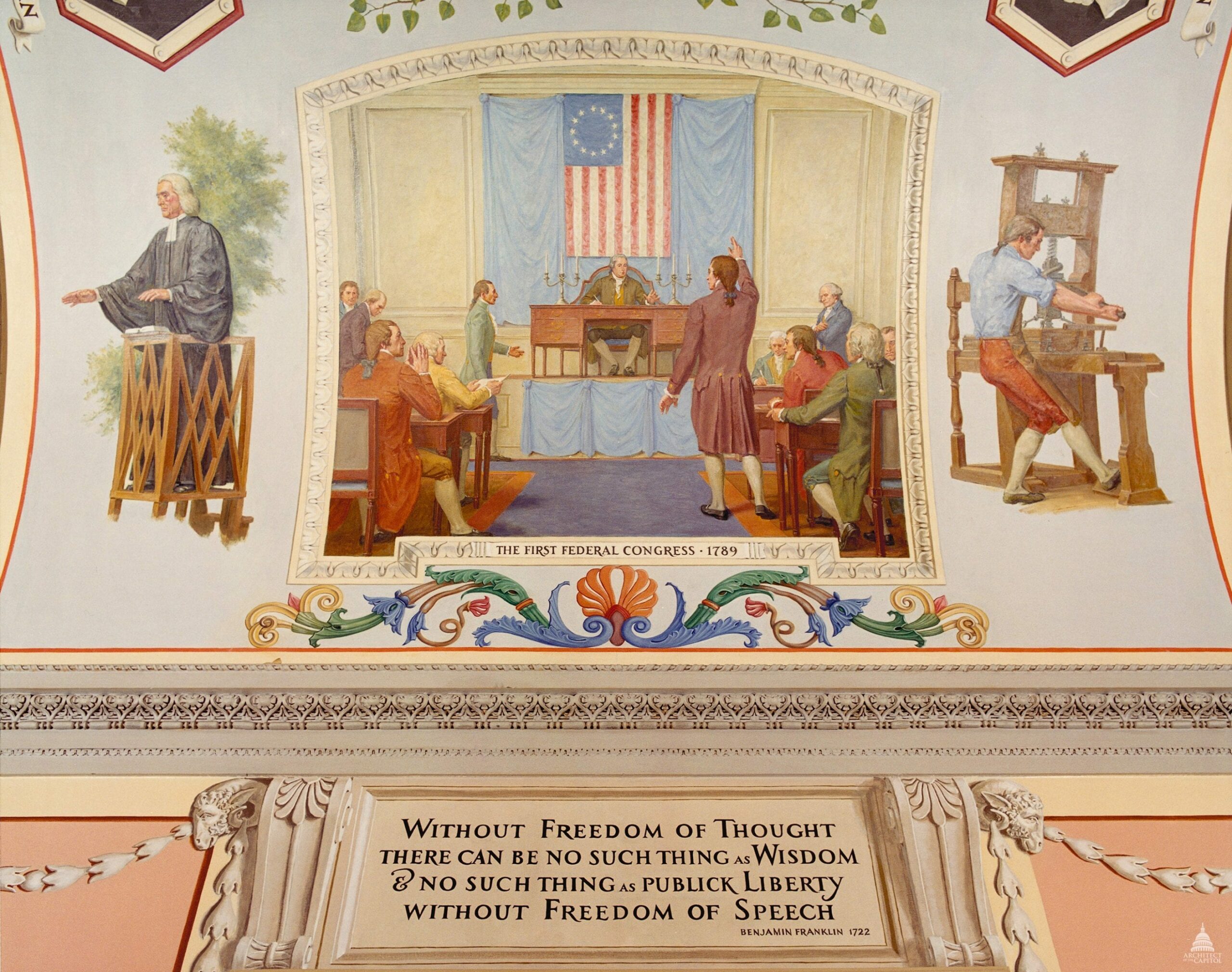

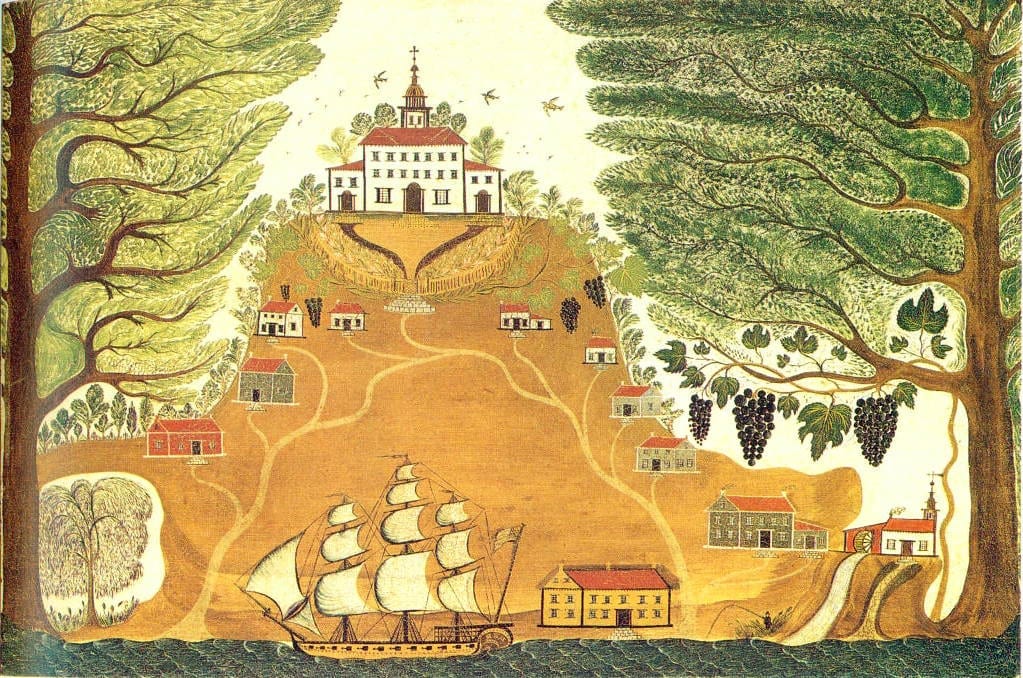

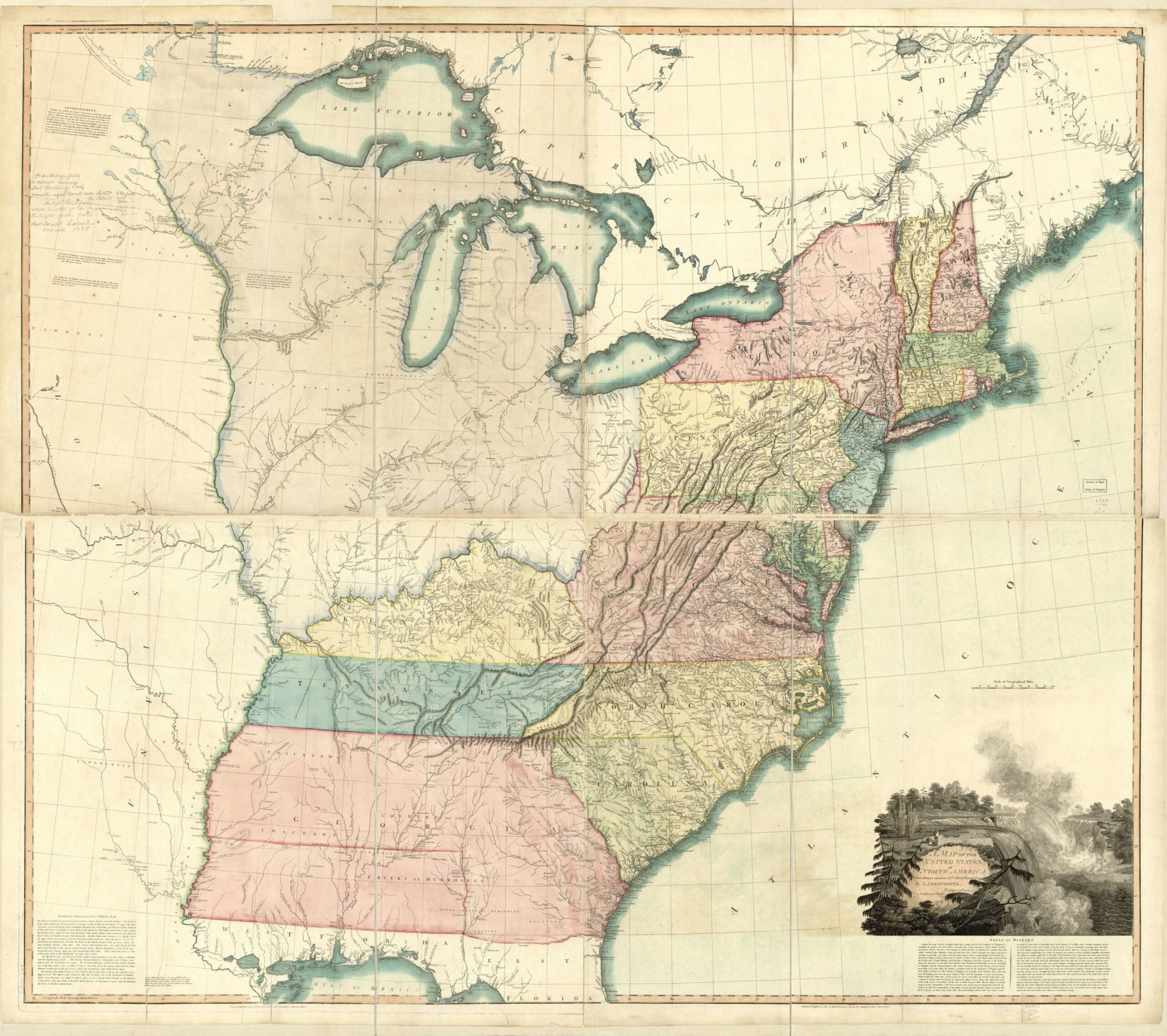

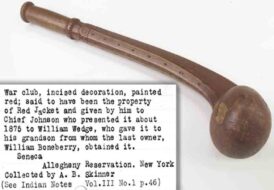

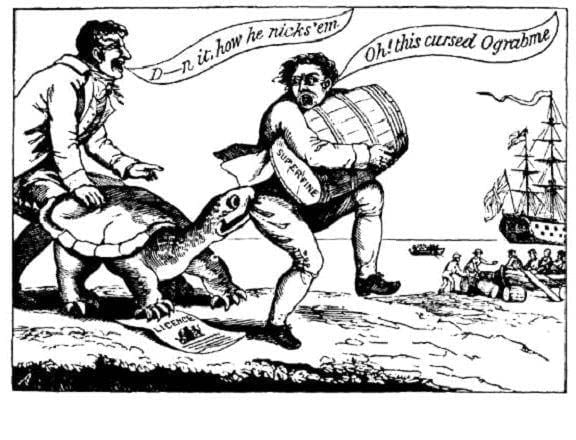

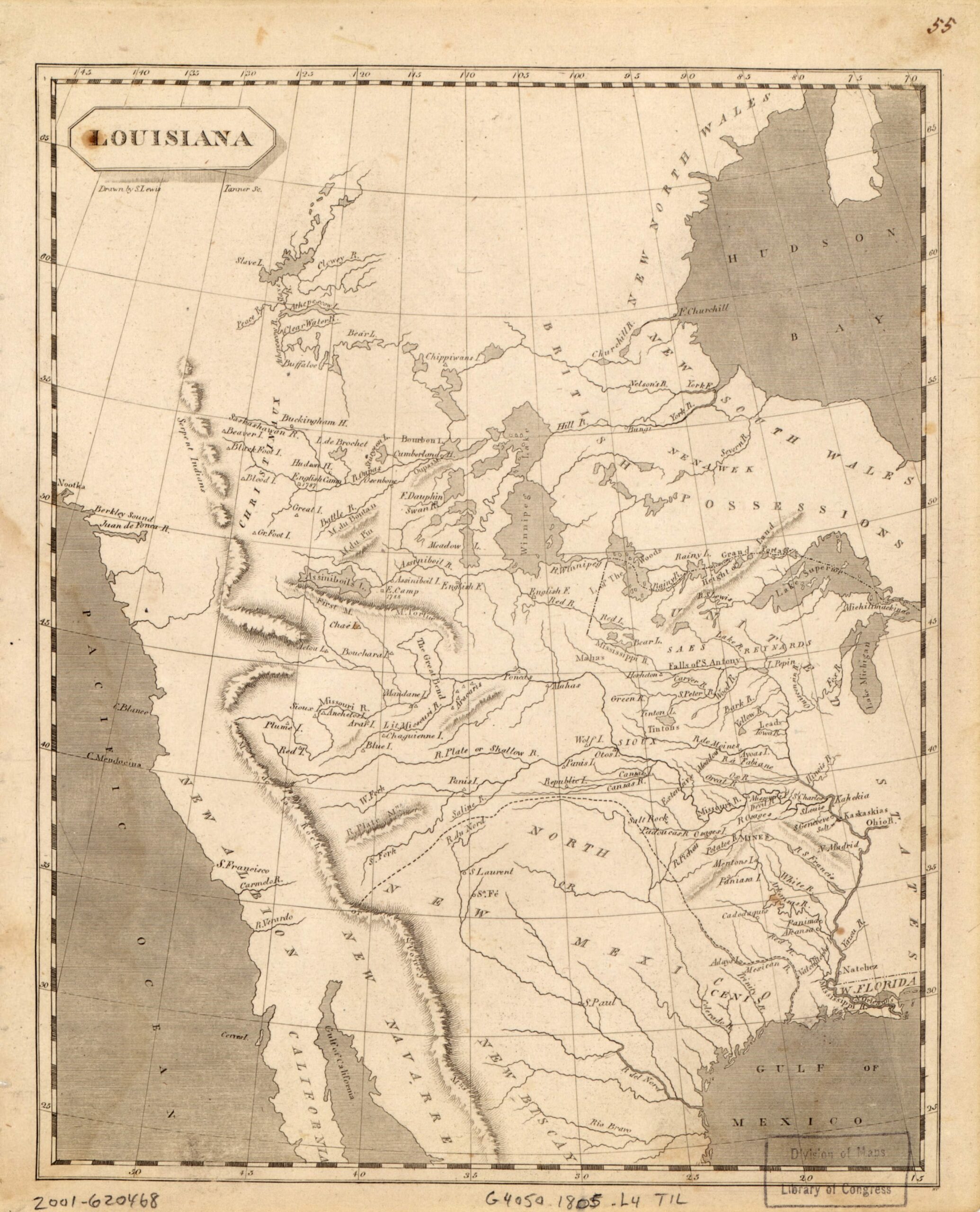

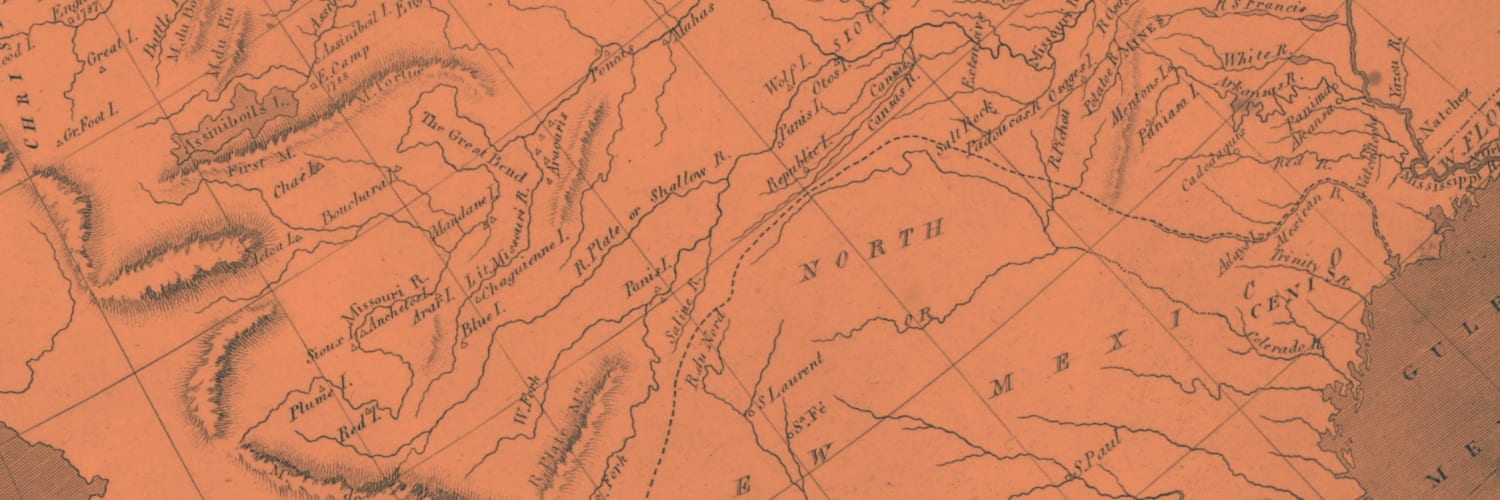

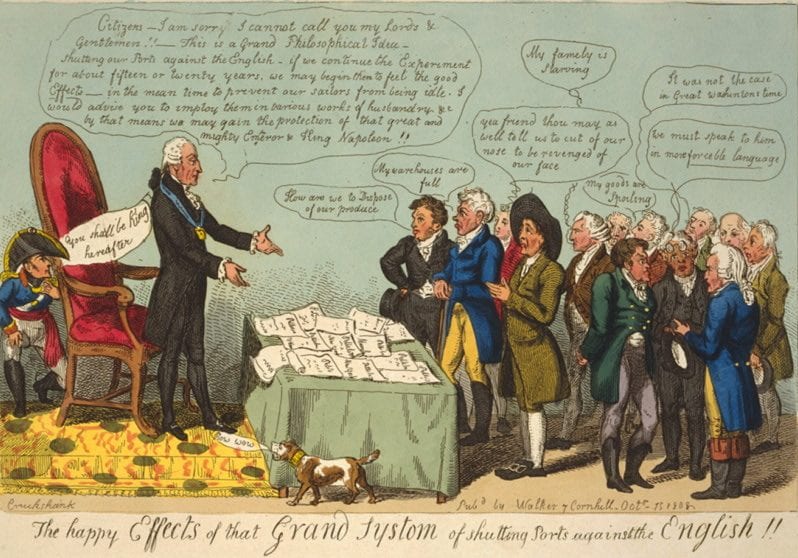

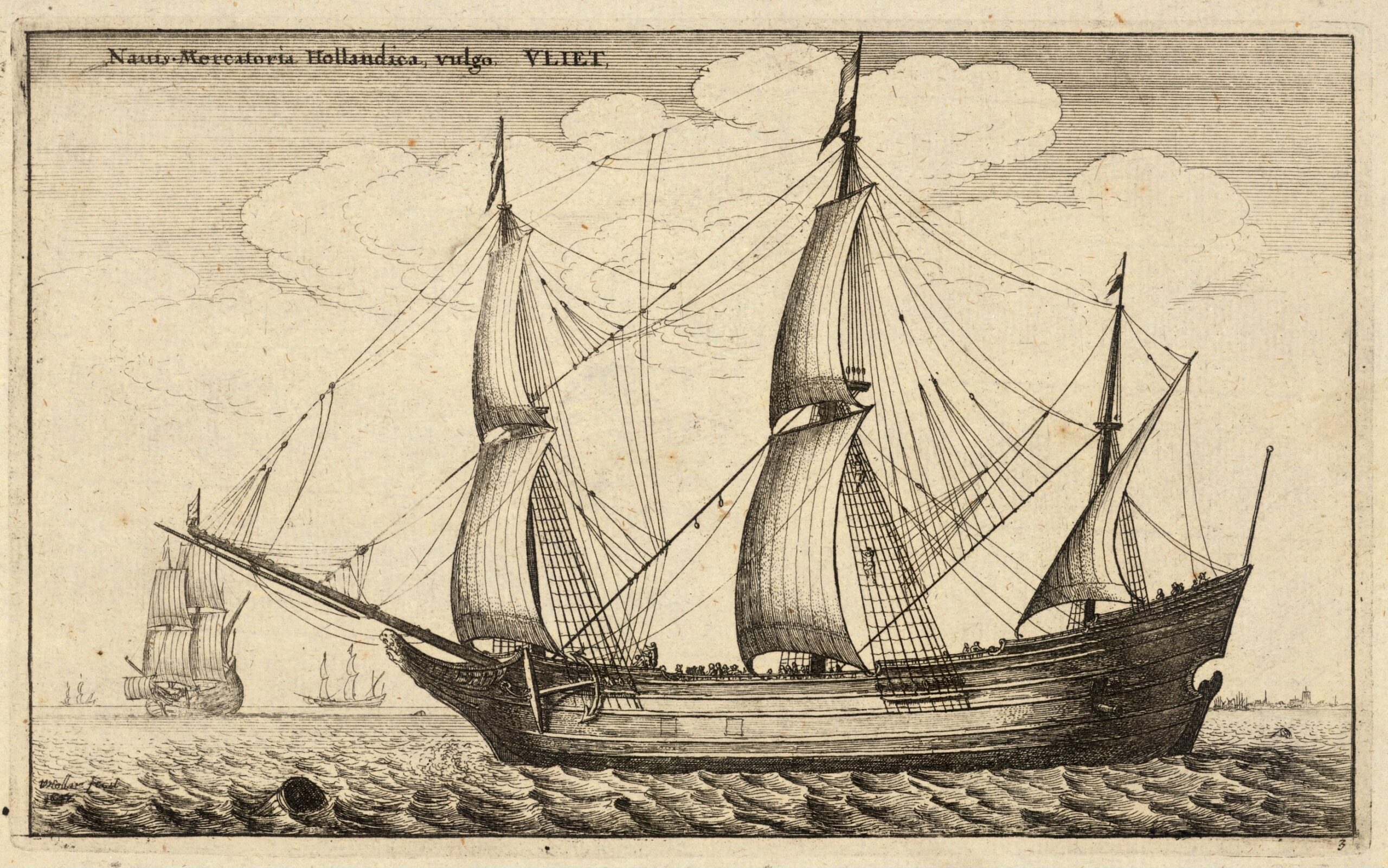

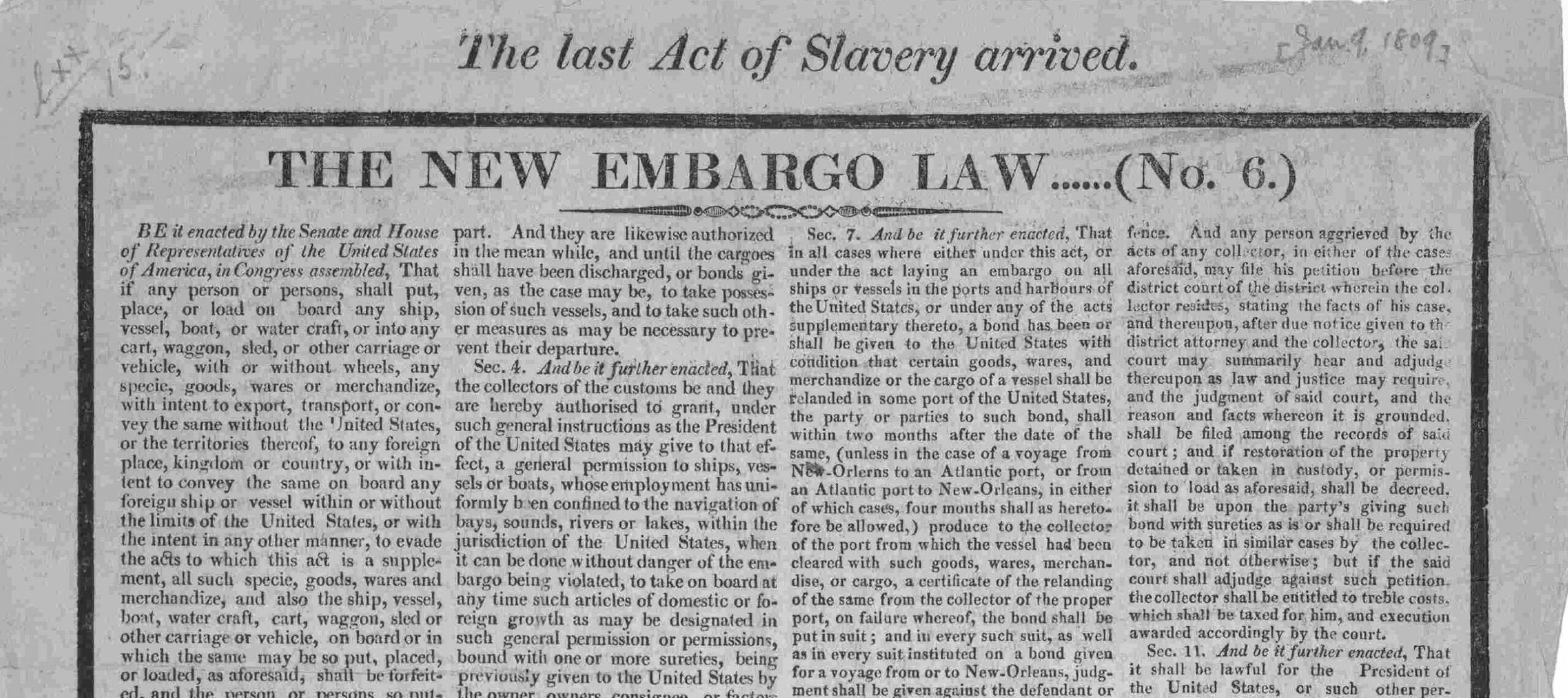

In 1791, the first Congress passed an excise tax on distilled alcohol, the first tax ever levied by the national government on a domestic manufacture. Farmers in the nation’s frontier counties (who commonly turned much of their grain crop into whiskey for easier transportation to eastern markets) bore the brunt of the tax and rapidly made their dissatisfaction with the policy known. Resistance was best organized in the four western counties of Pennsylvania, whose residents held a series of public meetings to draft petitions urging their representatives to repeal the law. At the same time, these meetings adopted resolutions advising individual non-compliance with the law, framing it as an unjust imposition upon the liberties of the people.

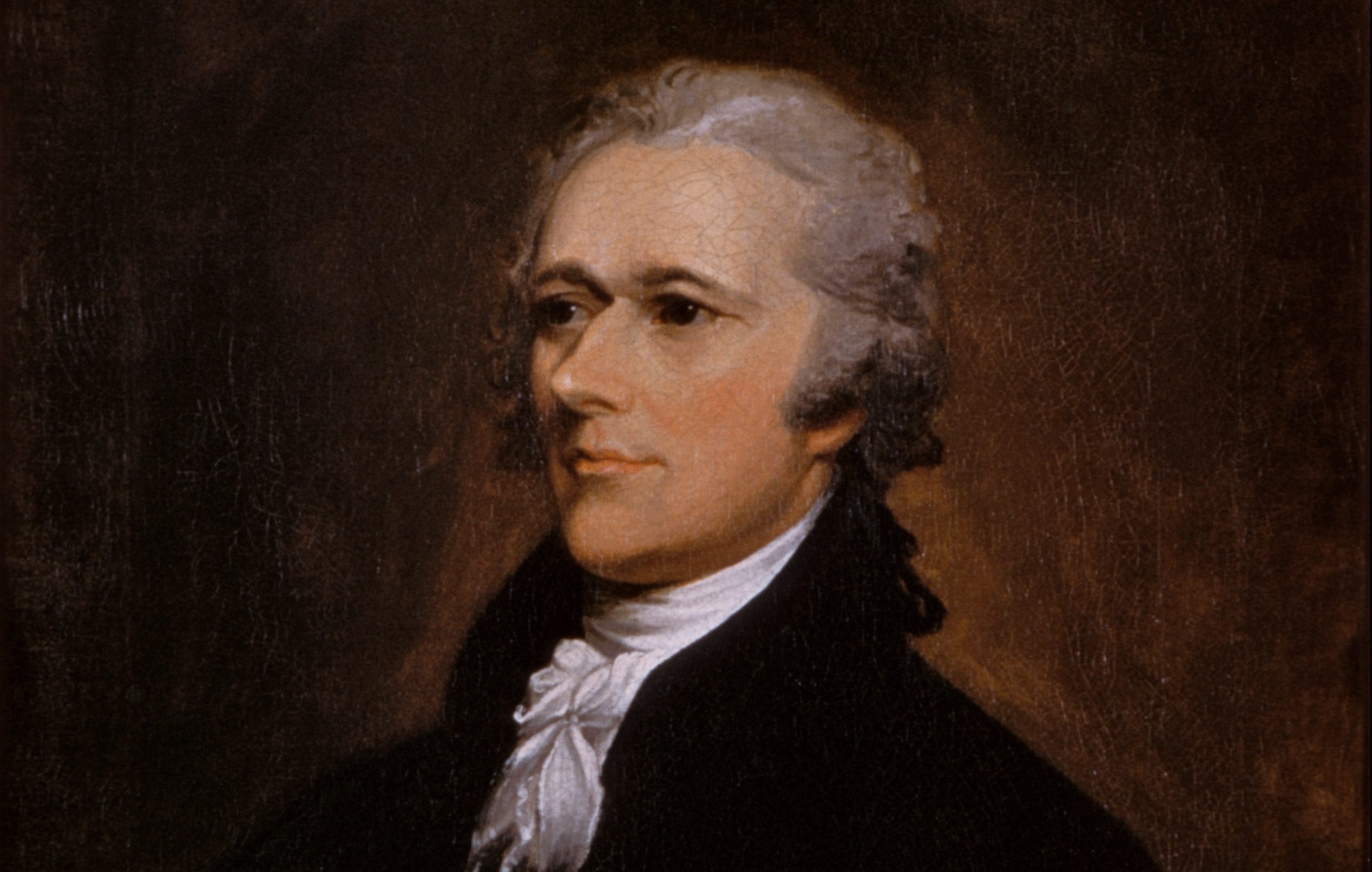

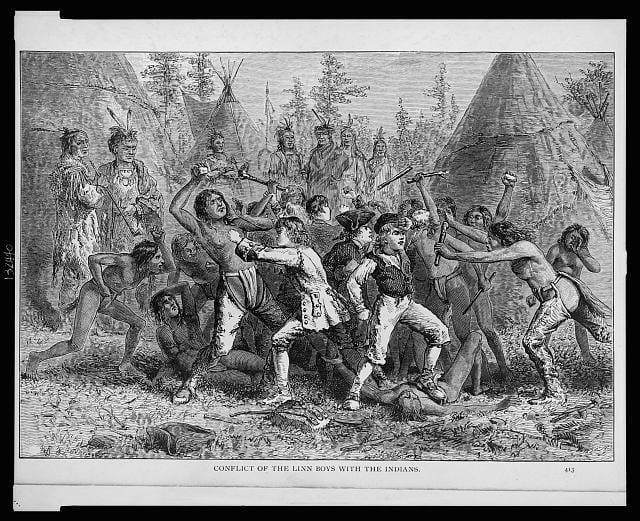

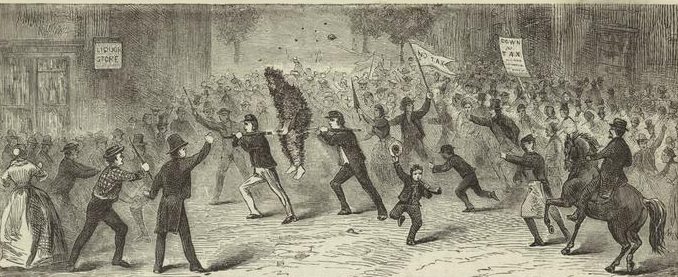

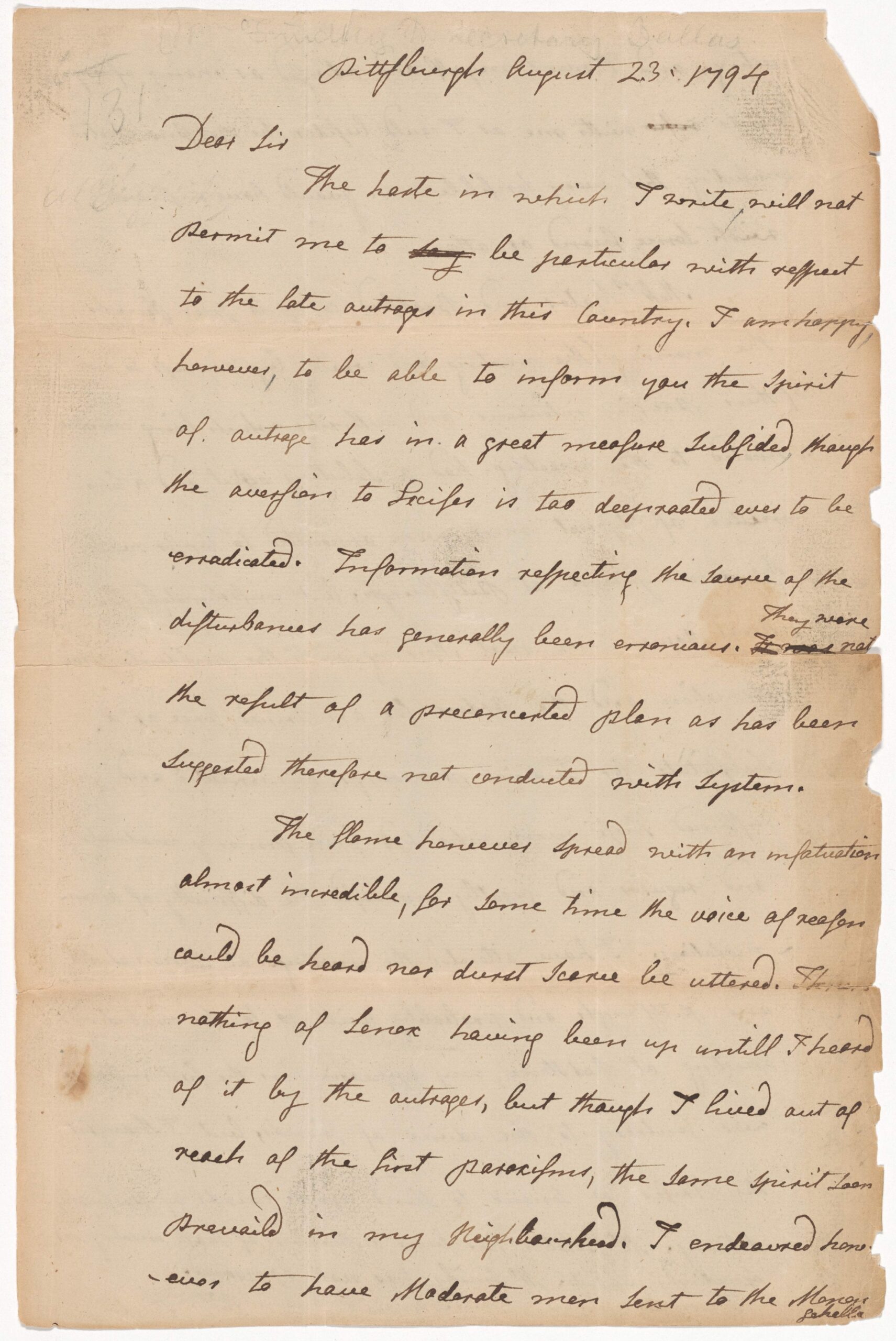

The conflict dragged on for several years, and when their initial efforts at peaceful non-compliance failed to secure the repeal of the excise, some western Pennsylvanians adopted tactics of violent resistance to the enforcement of the law. A number of excisemen were accosted in the line of duty, tarred and feathered and (in at least one instance) tied up outside overnight in an attempt to coerce them into renouncing their commissions. When accounts of the violence reached the national government in Philadelphia, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (whose department was ultimately responsible for the revenues collected by the excise) prepared a report for President George Washington.

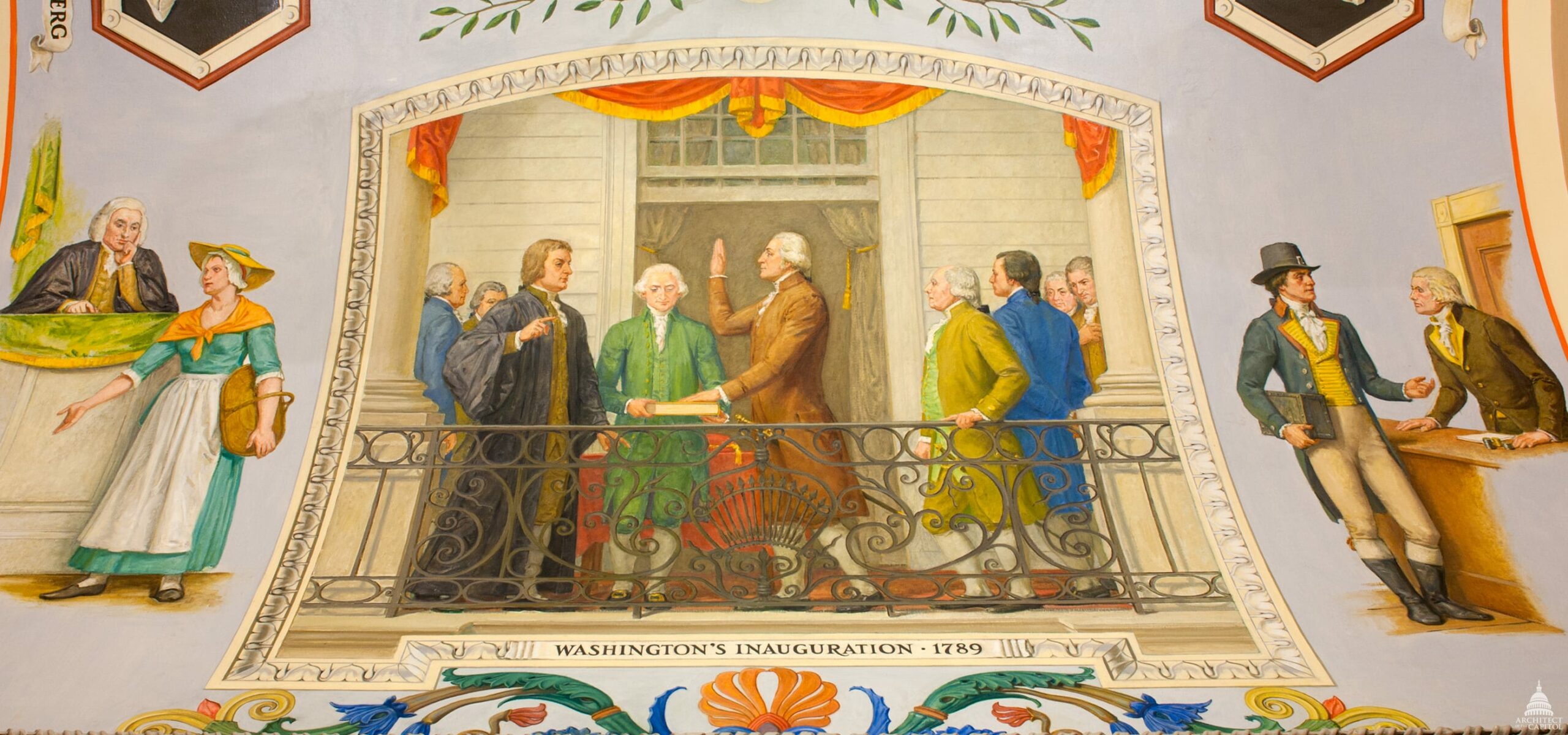

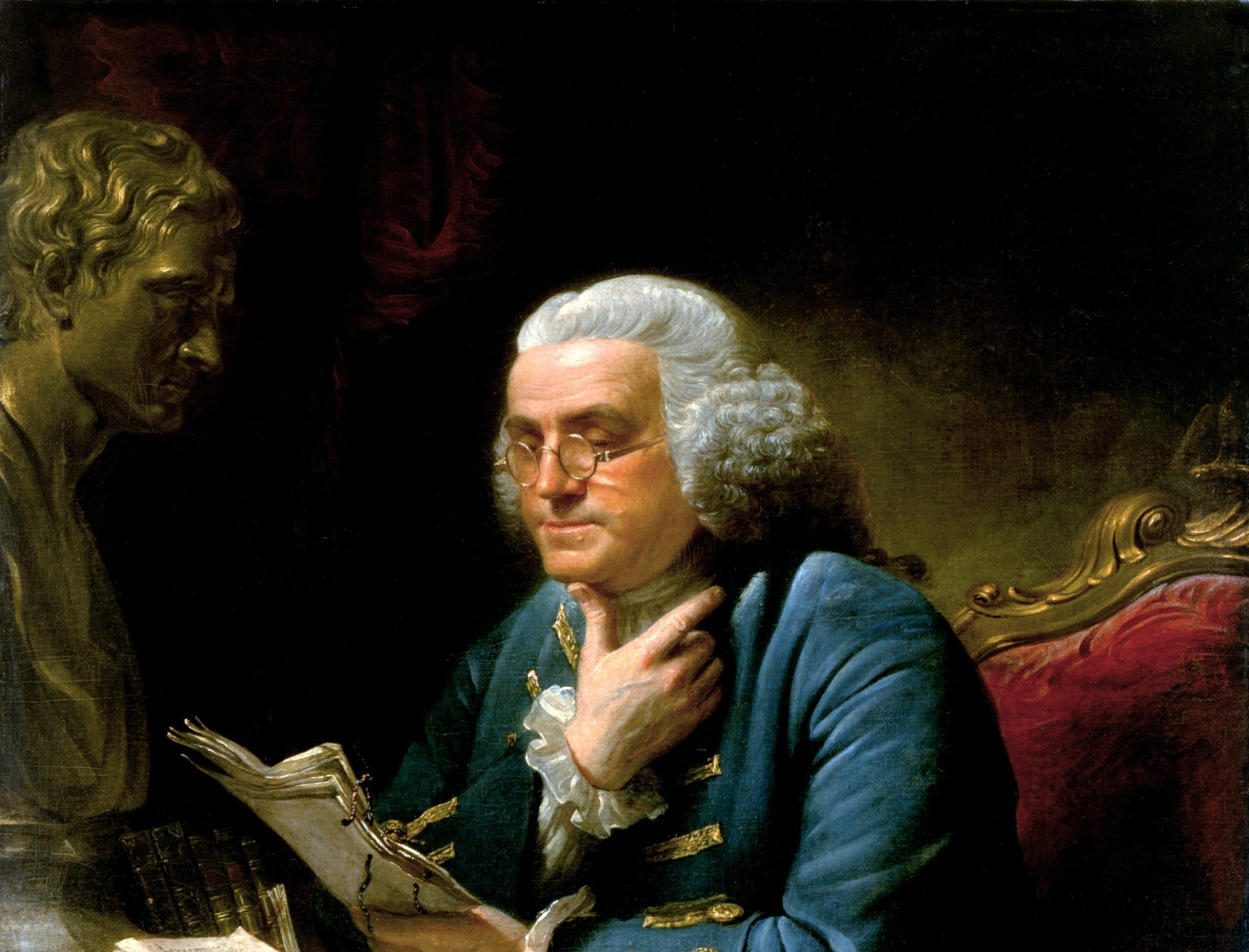

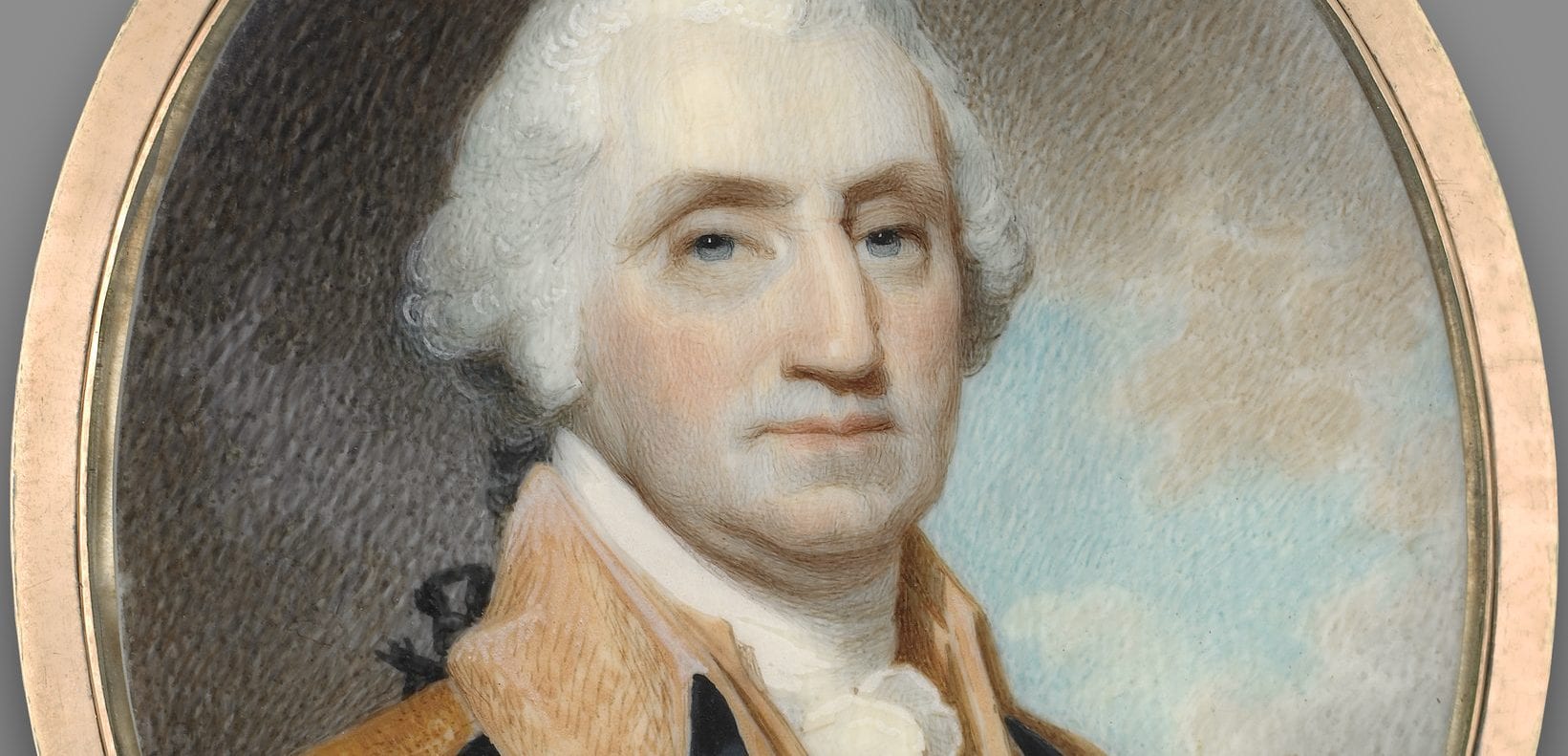

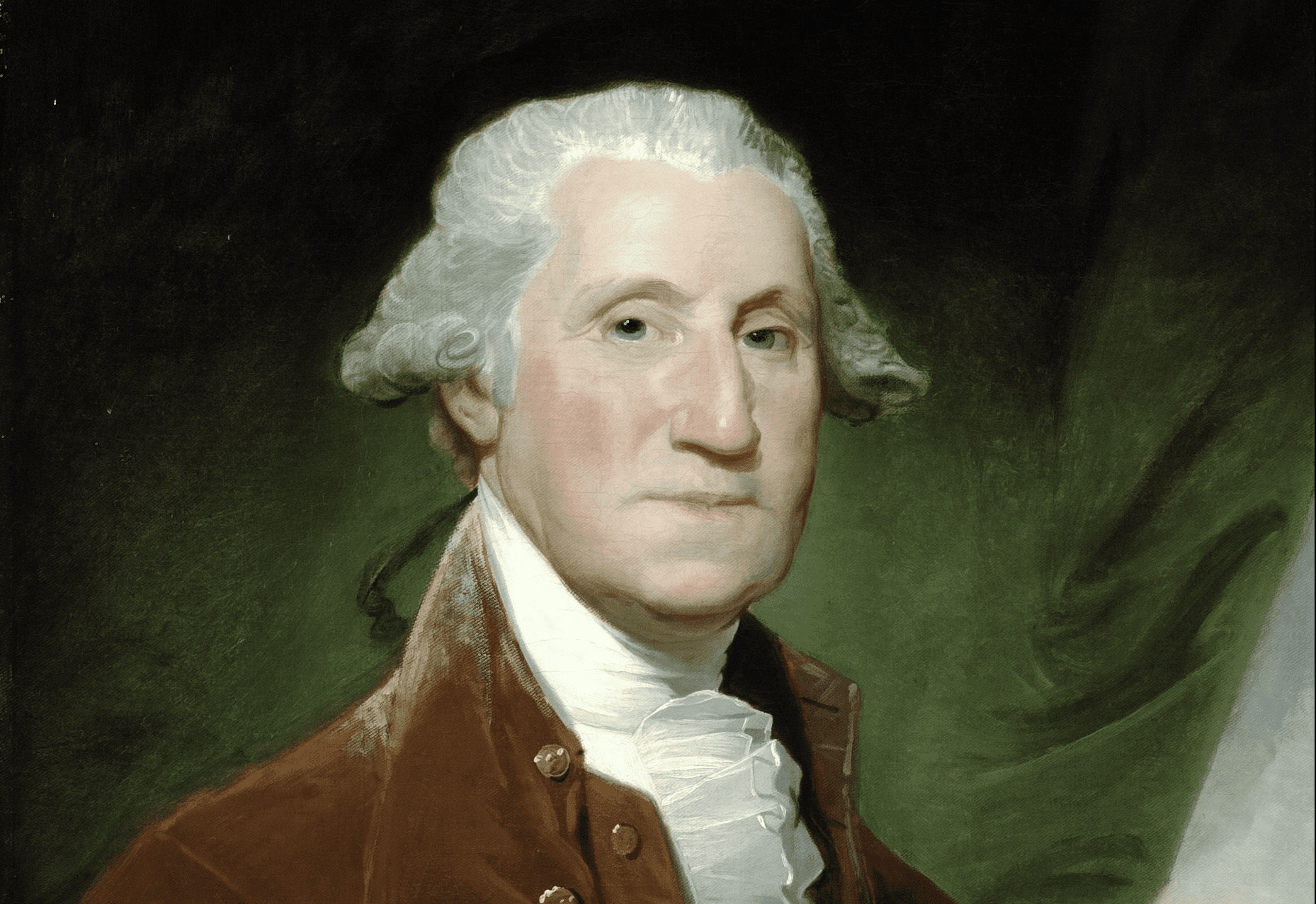

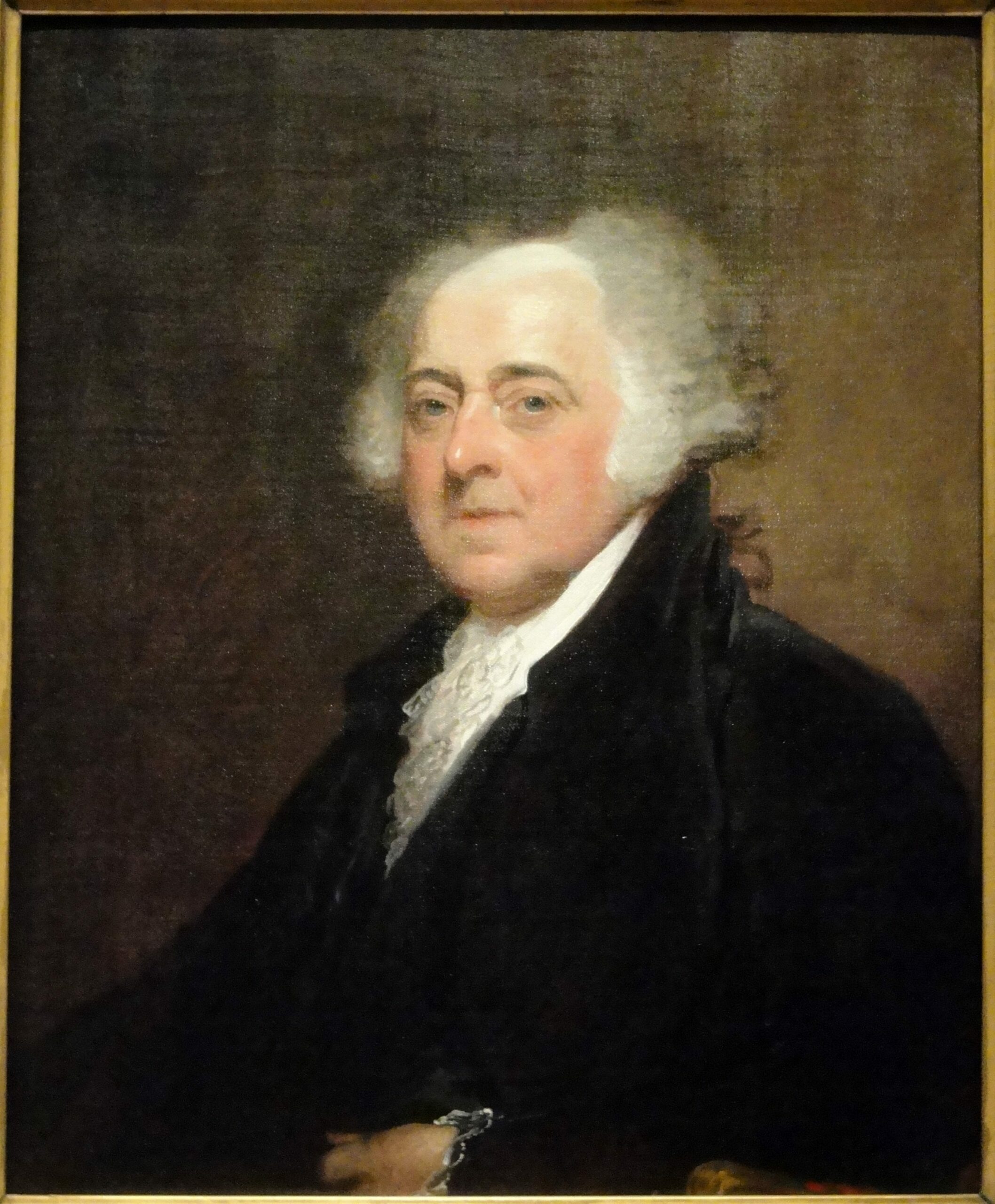

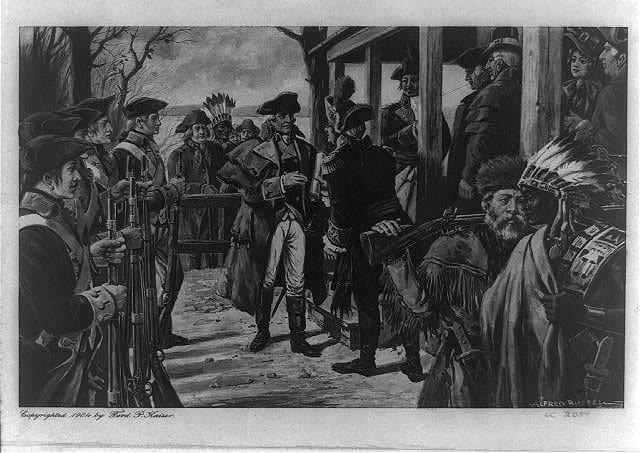

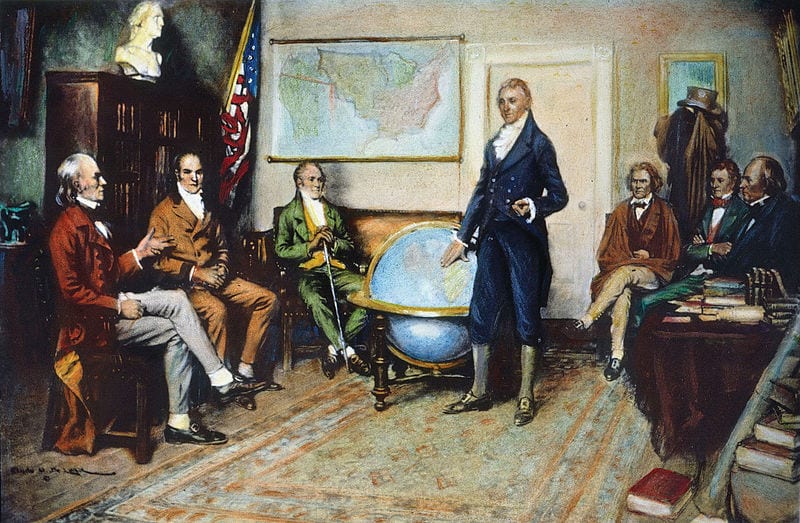

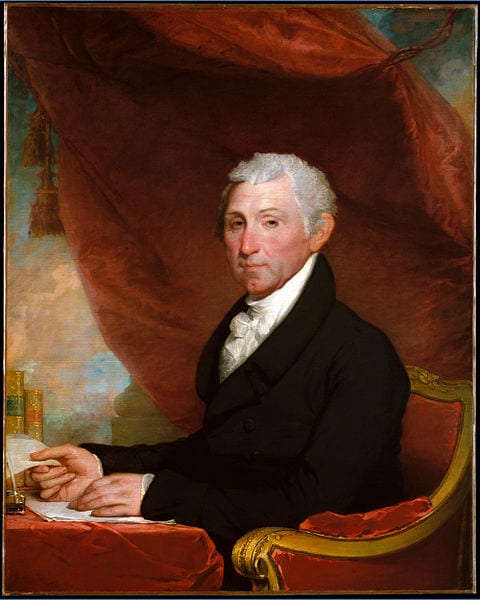

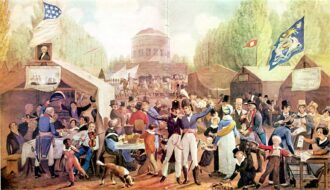

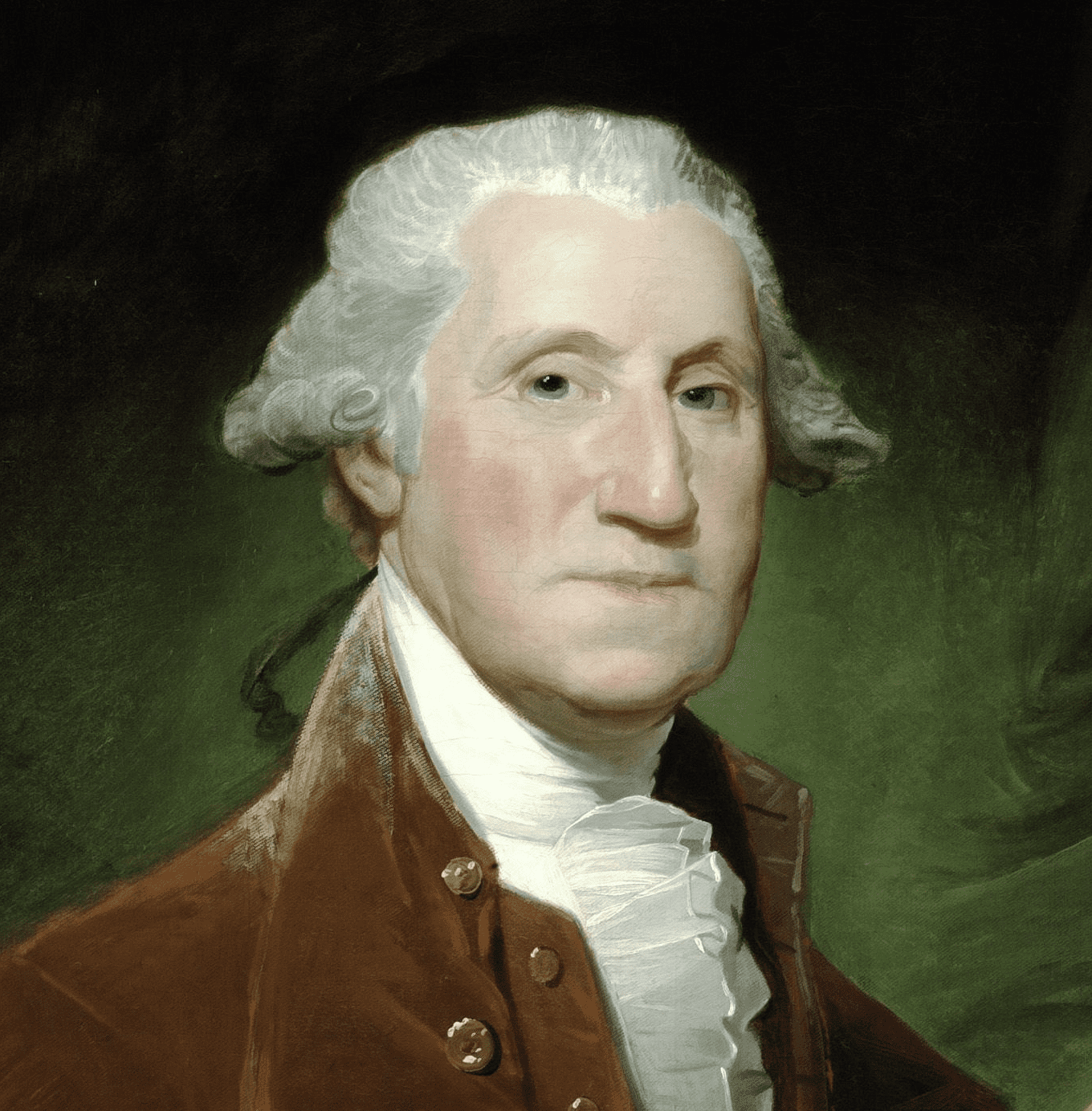

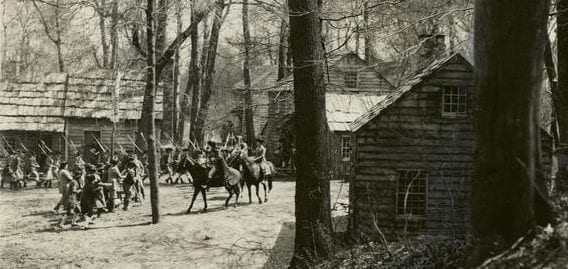

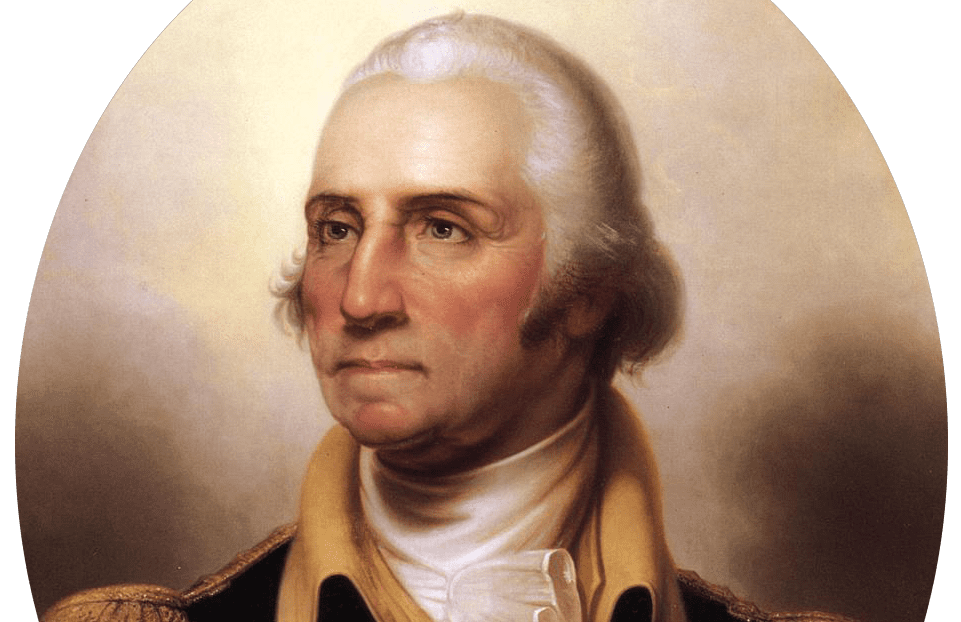

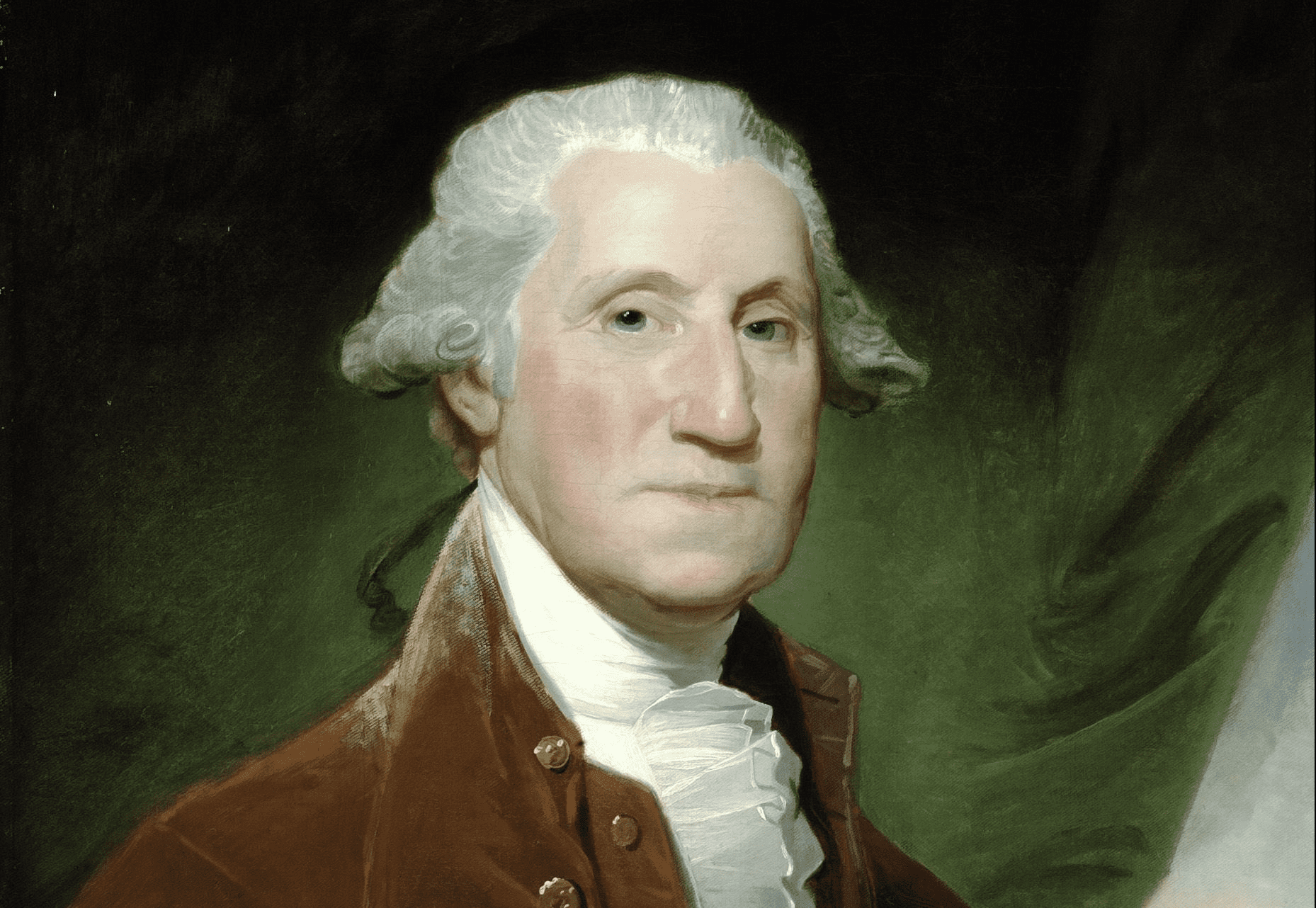

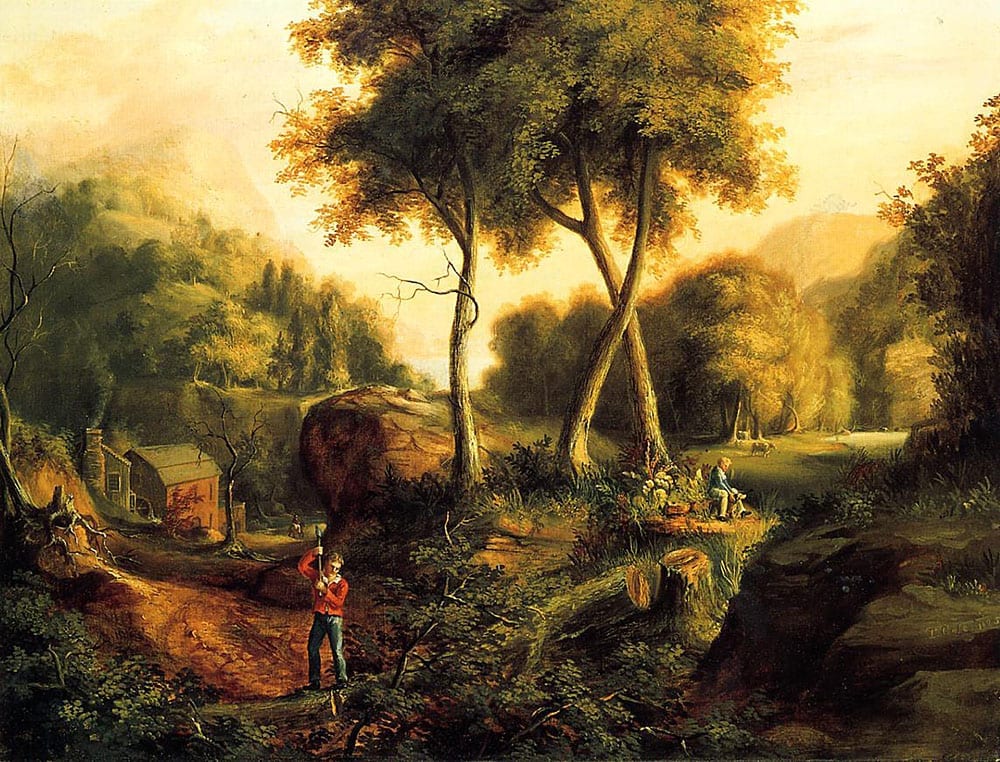

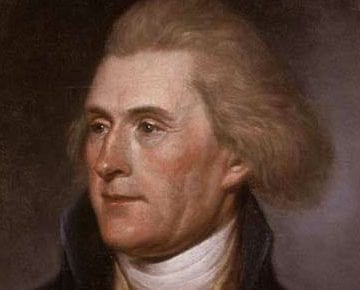

Hamilton’s report begins by describing the situation as a “disagreeable crisis” but ends by labeling the parties involved as insurgents, and their resistance as a domestic insurrection. He is frequently credited with convincing the president that matters would not be resolved apart from the use of military force, with the result that Washington issued a presidential proclamation to that effect. Meanwhile, Hamilton’s pseudonymous Tully essays were meant to turn public opinion against the rebellion and bolster public support for the president’s decision to send in the militia. (In actuality, Washington himself took command of the nearly 13,000 troops that were marched to the West in October 1794, the only time an American president has actually served as a combat commander while in office; see Frederick Kemmelmeyer’s painting of the event, Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland).

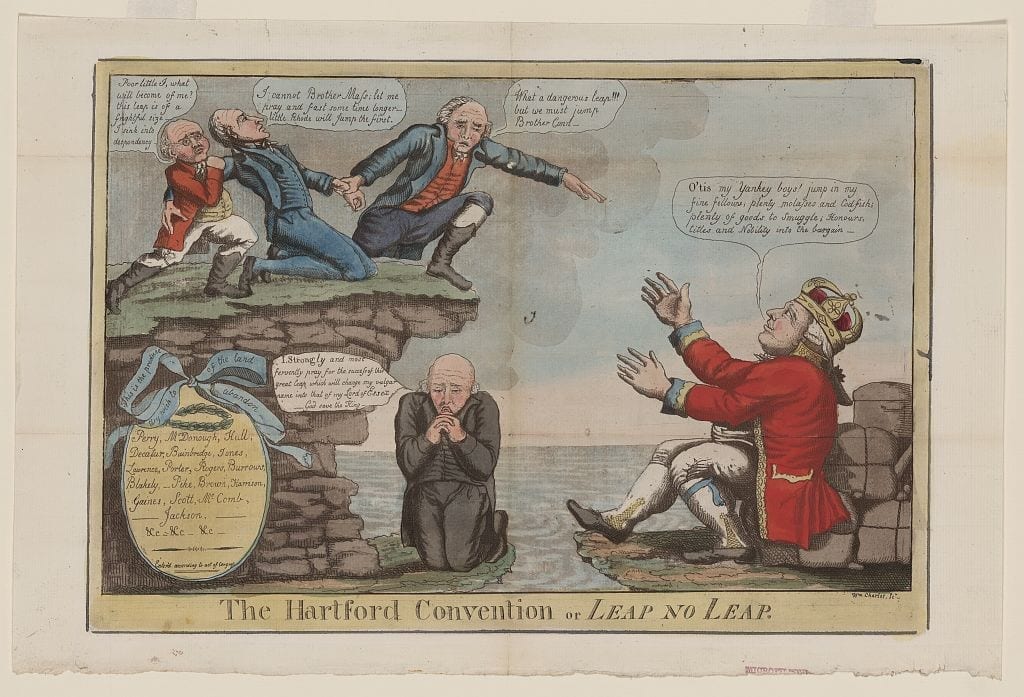

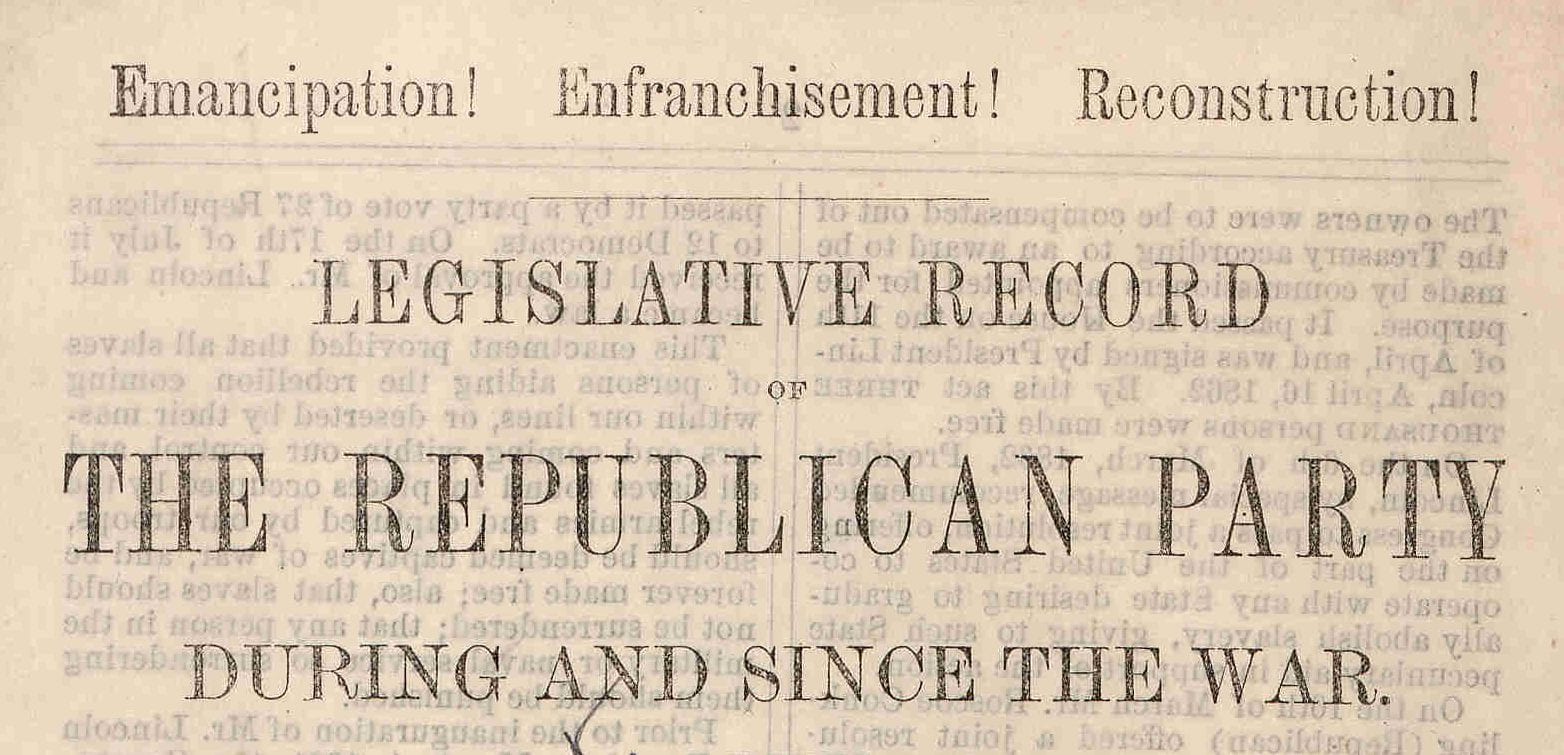

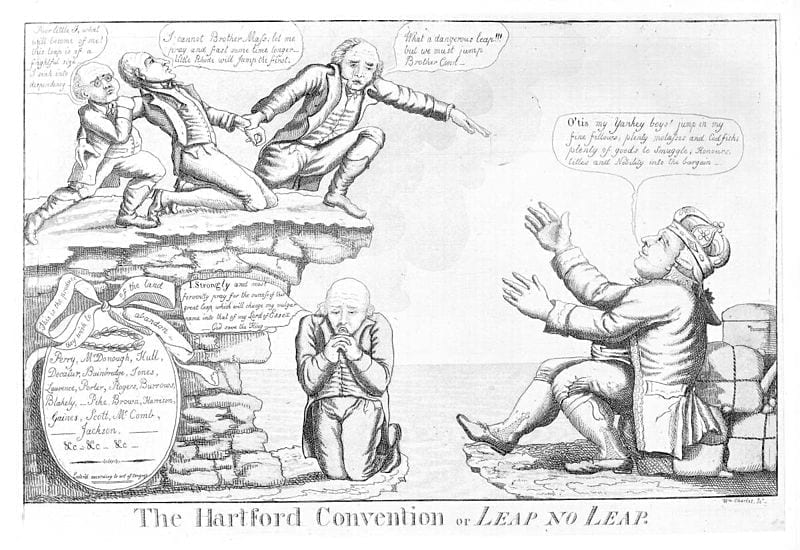

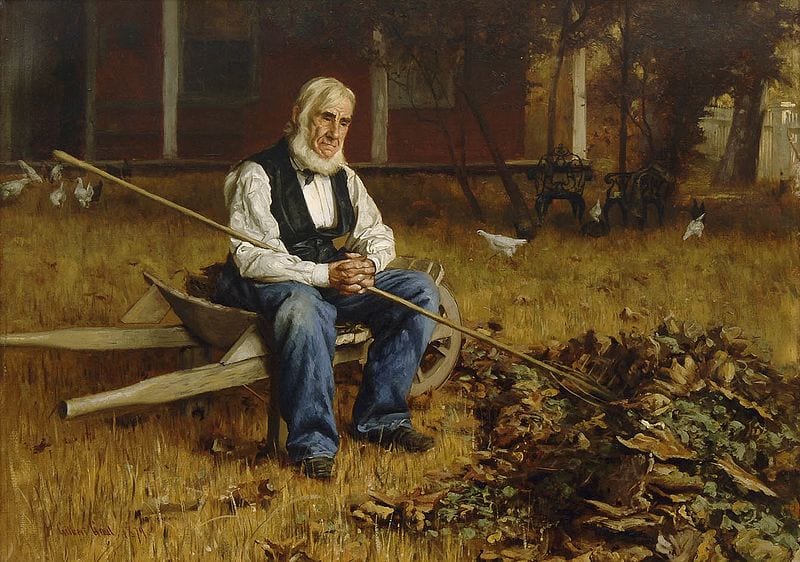

Hamilton’s essays and the marshaling of troops succeeded in quelling the rebellion without further violence. Yet the central question raised by the insurgency remained: to what extent and in what ways can citizens in a republic organize to resist laws they find unjust or immoral before becoming rebels or traitors? In the years following the incident, moderate opponents of the excise tax and other strongly national policies like it would offer opposing narratives of the insurrection in which they attempted to present the national government as oppressive.

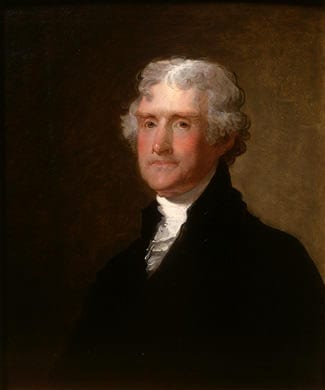

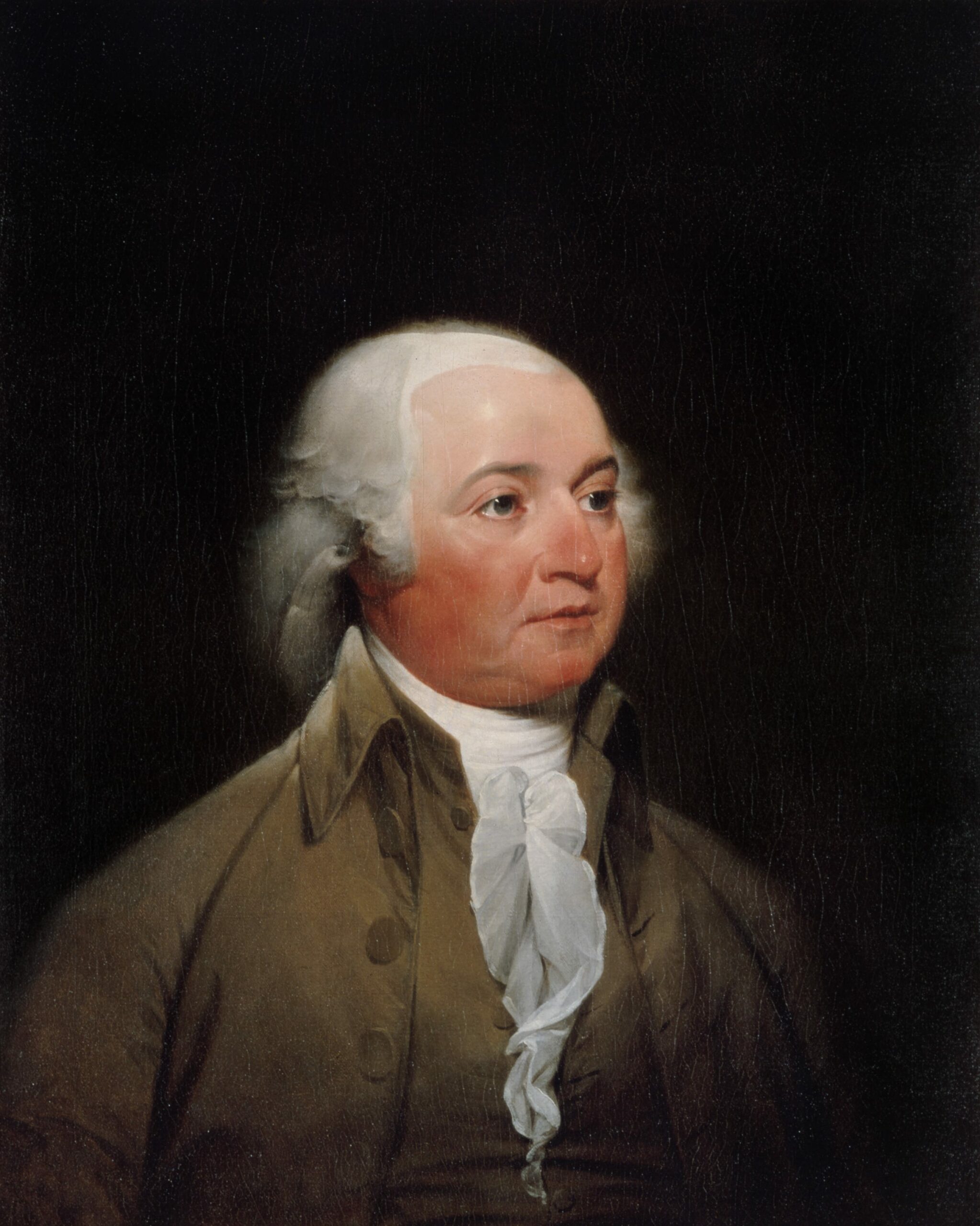

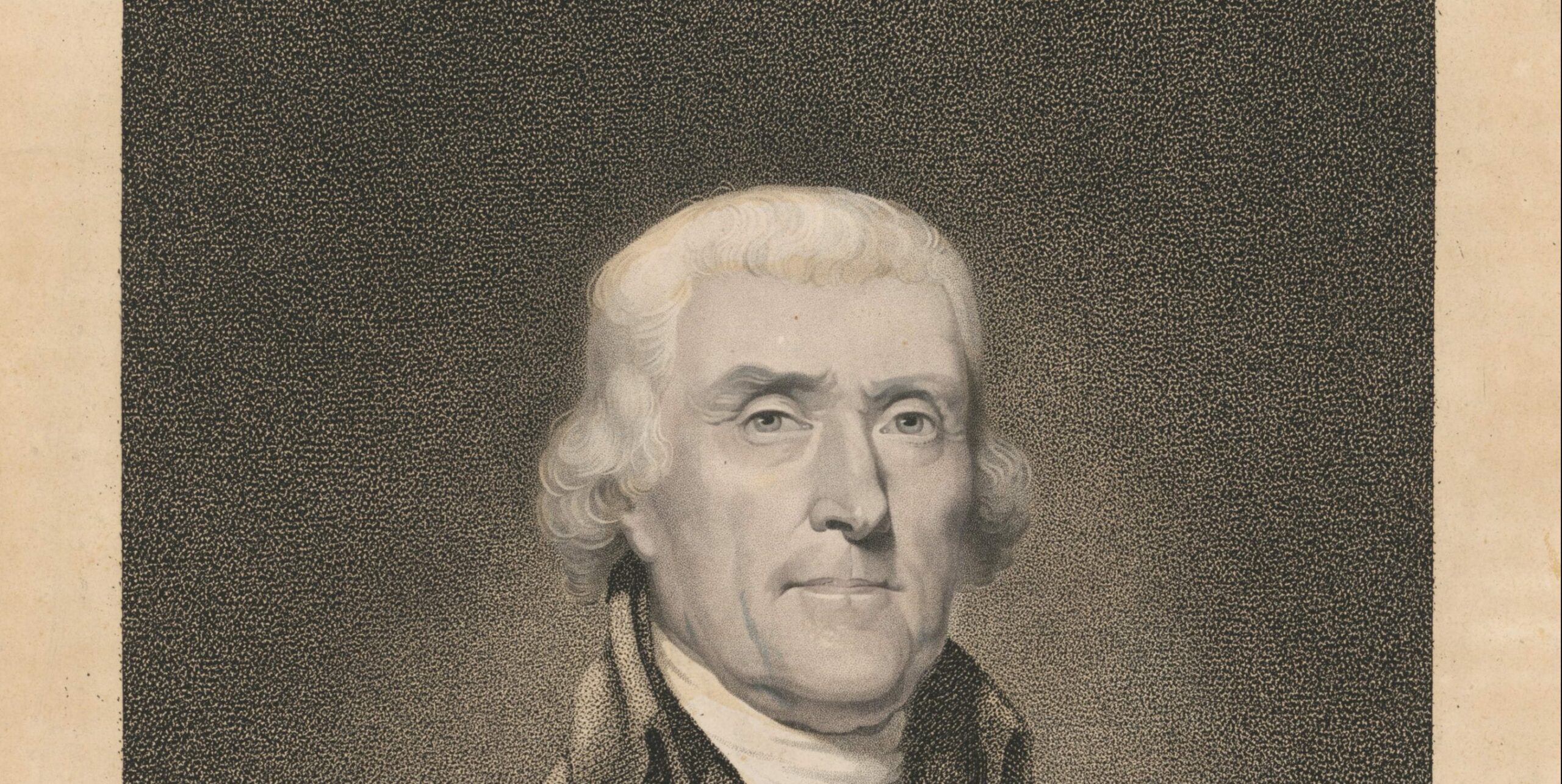

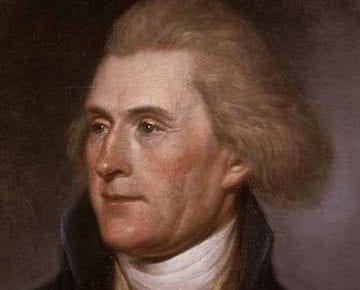

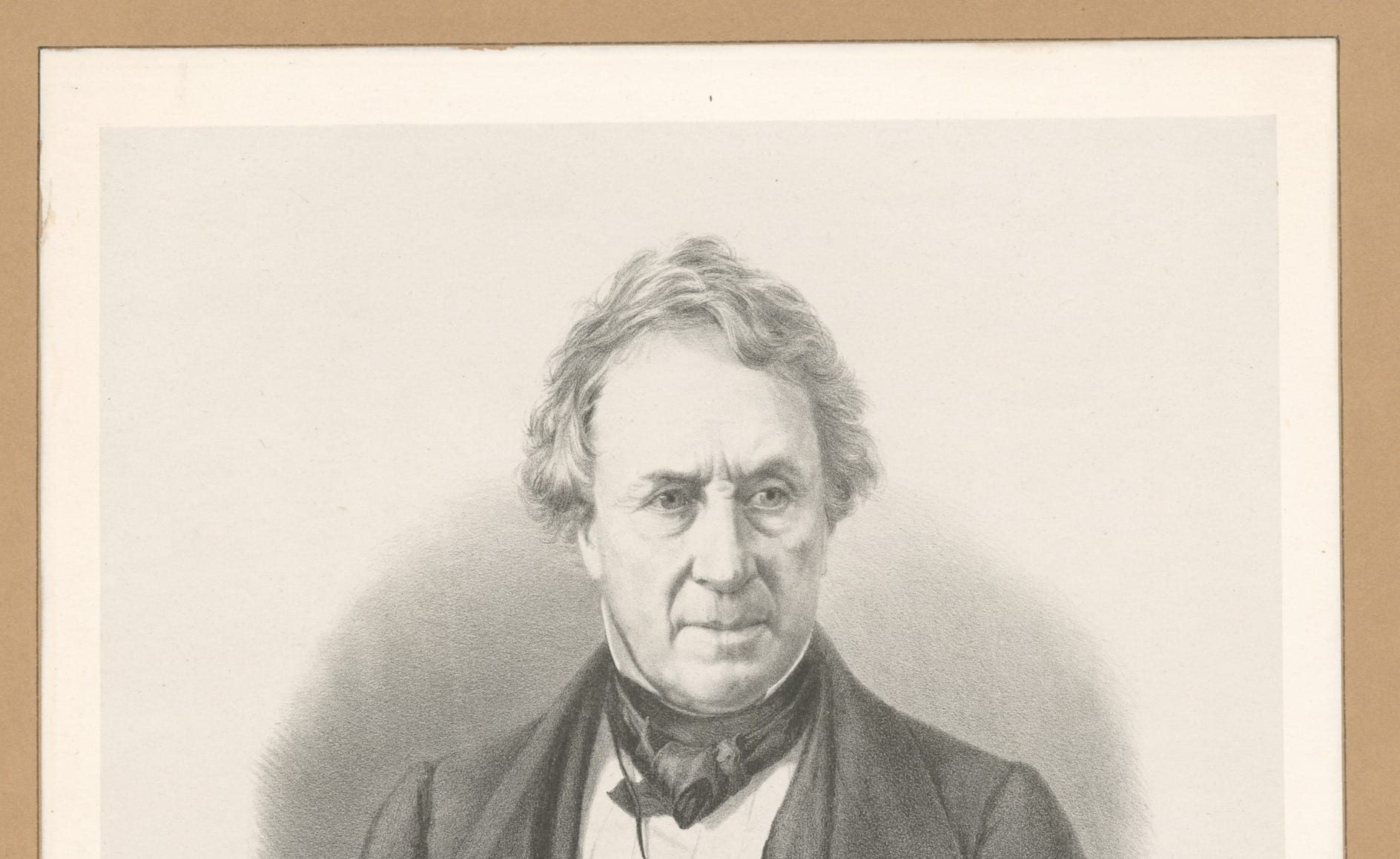

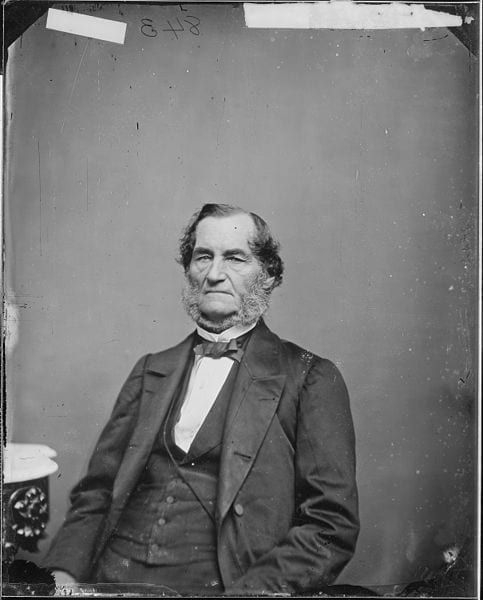

William Findley (a Republican from Western Pennsylvania who served as a long-time member of the House of Representatives), for example, downplays the violence of the rebels and instead focuses on the government’s attempt to restrict the freedoms of speech and association of individual citizens in his Defense of the Insurgents. Such interpretations were repeated by many others over the course of John Adams’s presidency and doubtlessly helped to bolster the rise of the Jeffersonian Republicans as a substantial opposition party within national politics.

Claypoole’s Daily Advertiser, August 11, 1794.

Whereas, combinations to defeat the execution of the laws laying duties upon spirits distilled within the United States and upon stills have from the time of the commencement of those laws existed in some of the western parts of Pennsylvania.

And whereas, the said combinations, proceeding in a manner subversive equally of the just authority of government and of the rights of individuals, have hitherto effected their dangerous and criminal purpose by the influence of certain irregular meetings whose proceedings have tended to encourage and uphold the spirit of opposition by misrepresentations of the laws calculated to render them odious; by endeavors to deter those who might be so disposed from accepting offices under them through fear of public resentment and of injury to person and property, and to compel those who had accepted such offices by actual violence to surrender or forbear the execution of them; by circulation of vindictive menaces against all those who should otherwise, directly or indirectly, aid in the execution of the said laws, or who, yielding to the dictates of conscience and to a sense of obligation, should themselves comply therewith; by actually injuring and destroying the property of persons who were understood to have so complied; by inflicting cruel and humiliating punishments upon private citizens for no other cause than that of appearing to be the friends of the laws; by intercepting the public officers on the highways, abusing, assaulting, and otherwise ill-treating them; by going into their houses in the night, gaining admittance by force, taking away their papers, and committing other outrages, employing for these unwarrantable purposes the agency of armed banditti disguised in such manner as for the most part to escape discovery;

And whereas . . . the endeavors of the executive officers to conciliate a compliance with the laws by explanations, by forbearance, and even by particular accommodations founded on the suggestion of local considerations, have been disappointed of their effect by the machinations of persons whose industry to excite resistance has increased with every appearance of a disposition among the people to relax in their opposition and to acquiesce in the laws, insomuch that many persons in the said western parts of Pennsylvania have at length been hardy enough to perpetrate acts, which I am advised amount to treason, being overt acts of levying war against the United States. . . .

And whereas, it is in my judgment necessary under the circumstances of the case to take measures for calling forth the militia in order to suppress the combinations aforesaid, and to cause the laws to be duly executed; and I have accordingly determined so to do, feeling the deepest regret for the occasion, but withal the most solemn conviction that the essential interests of the Union demand it, that the very existence of government and the fundamental principles of social order are materially involved in the issue, and that the patriotism and firmness of all good citizens are seriously called upon, as occasions may require, to aid in the effectual suppression of so fatal a spirit;

Therefore, and in pursuance of the proviso above recited, I, George Washington, President of the United States, do hereby command all persons, being insurgents, as aforesaid, and all others whom it may concern, on or before the 1st day of September next to disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes. And I do moreover warn all persons whomsoever against aiding, abetting, or comforting the perpetrators of the aforesaid treasonable acts; and do require all officers and other citizens, according to their respective duties and the laws of the land, to exert their utmost endeavors to prevent and suppress such dangerous proceedings. . . .

G. WASHINGTON