Introduction

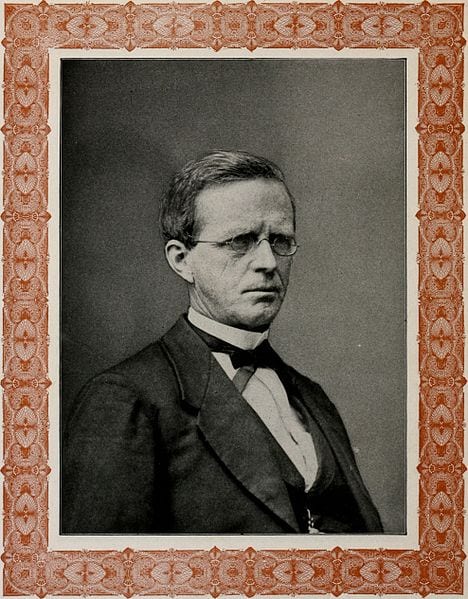

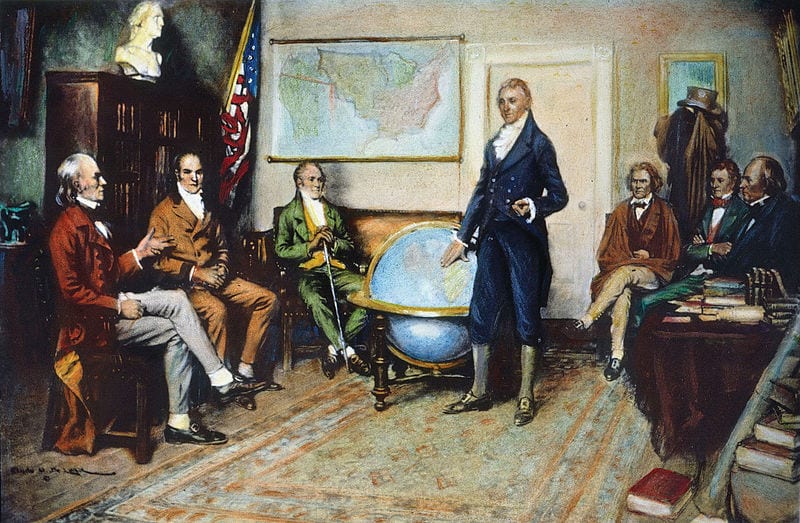

John Holmes was a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts and one of the earliest supporters of the Missouri Compromise in Congress. Before moving to the U.S. Senate as one of the first two senators from the newly formed state of Maine, he mailed a letter to Thomas Jefferson with a copy of a pamphlet he had published to the citizens of Maine on the Missouri question. Jefferson, in retirement at Monticello, responded to Holmes’s inquiry shortly after the passage of the Missouri Compromise. In his response, Jefferson congratulated Holmes on his defense of the measure, but worried about the effects of drawing a literal line of separation across the nation in regard to a moral and political principle. Jefferson, himself a slave-owner, makes clear in the rest of the letter not only his hatred of slavery, but his personal desire to see all men everywhere free.

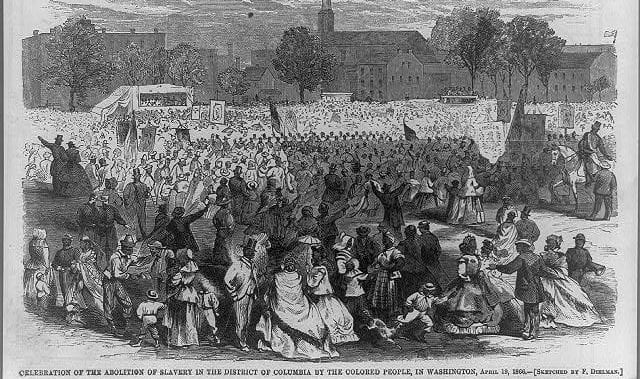

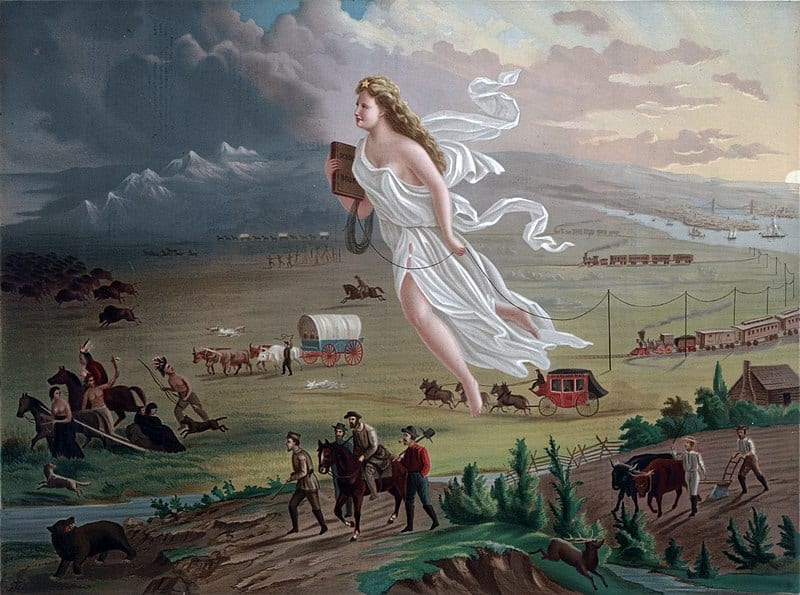

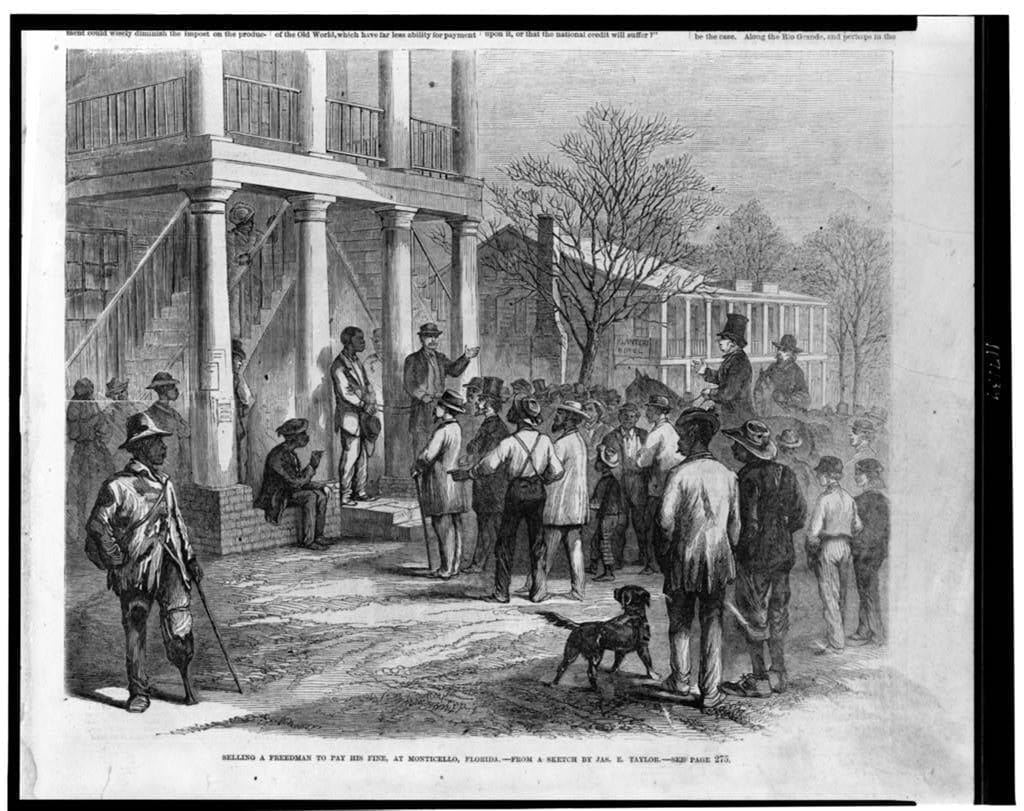

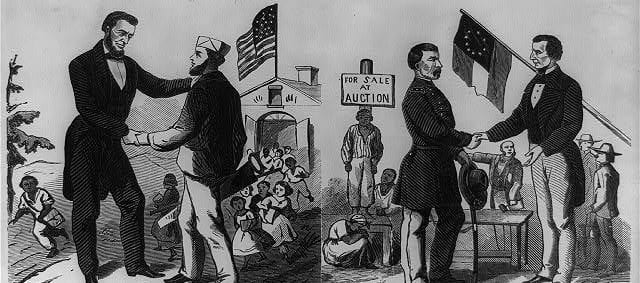

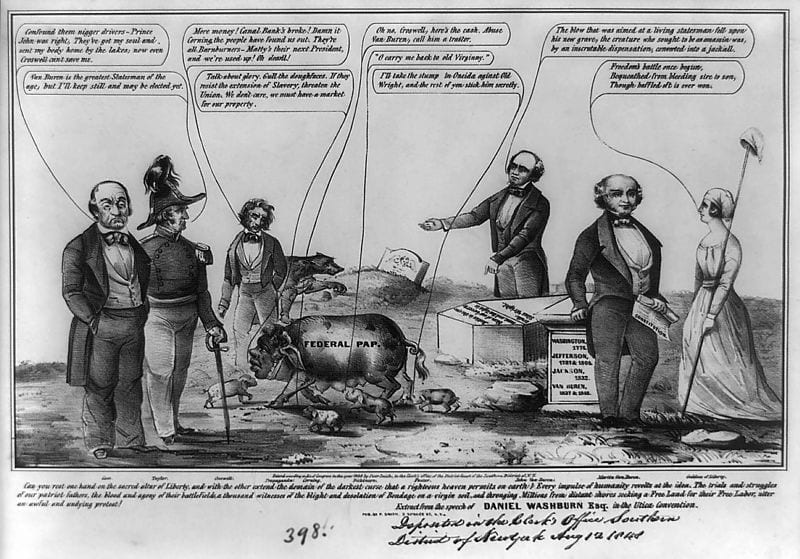

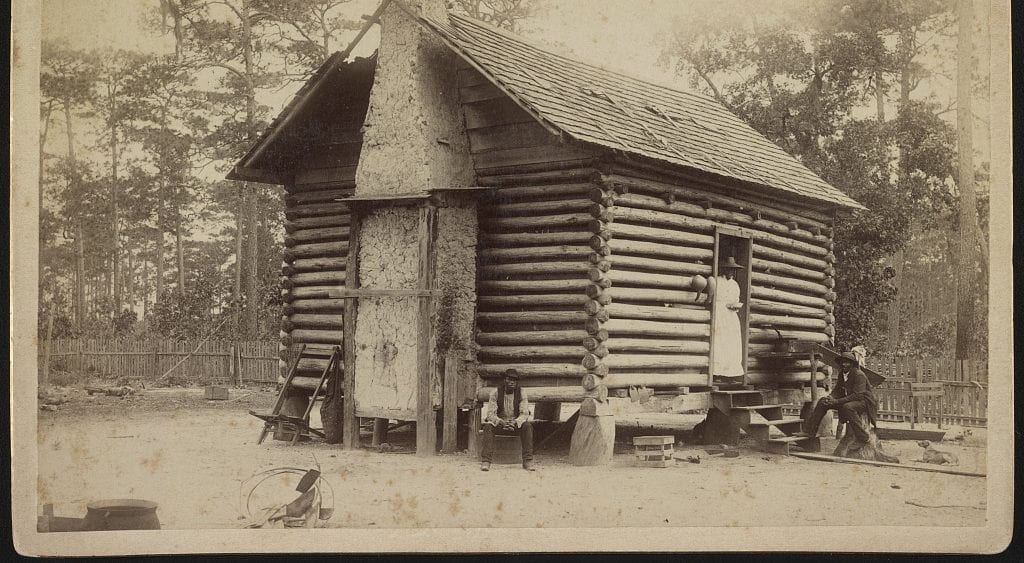

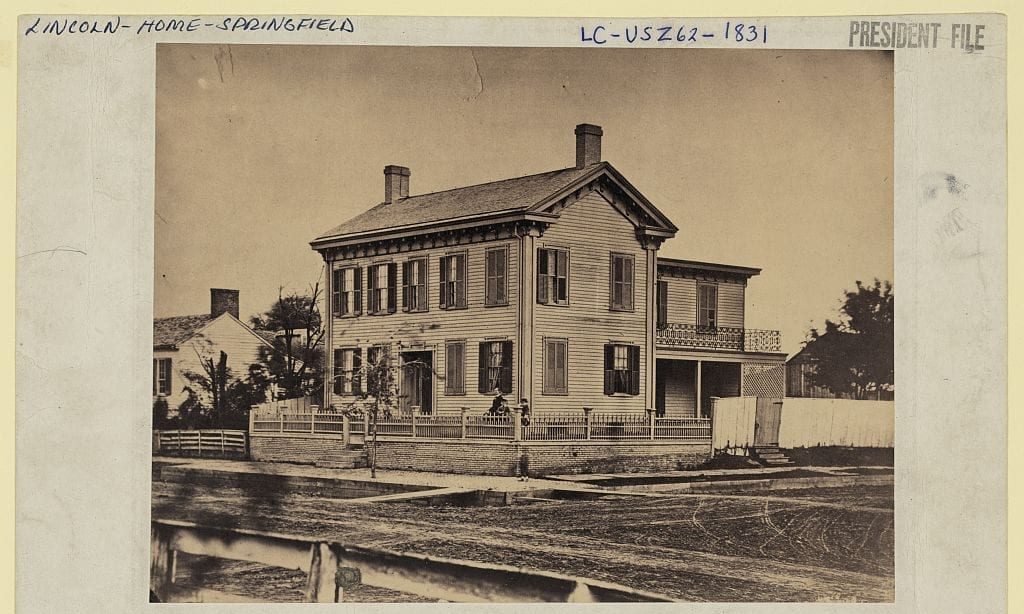

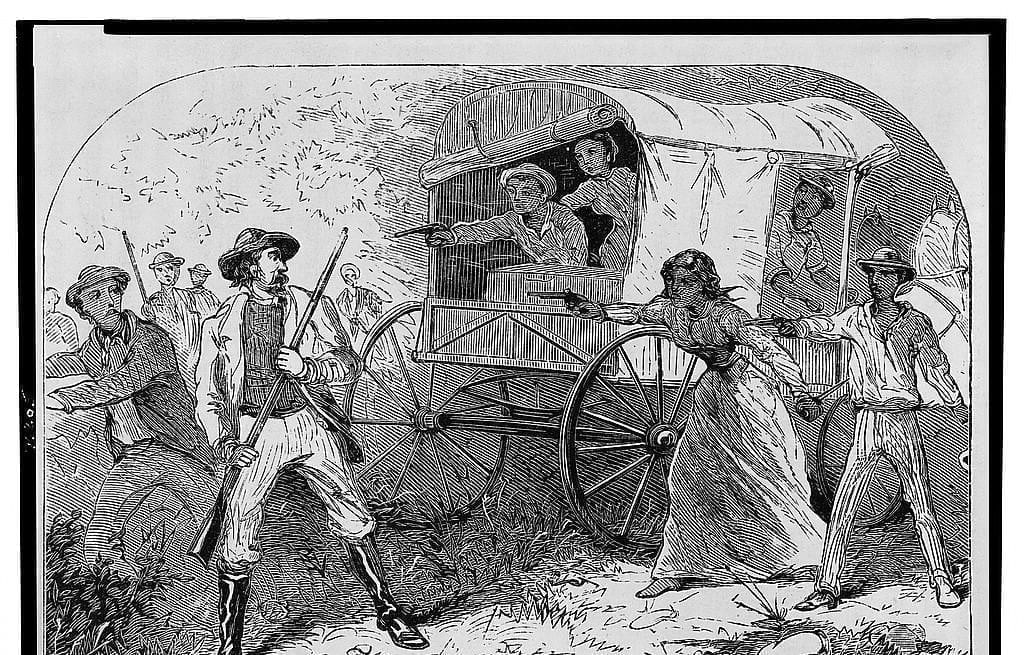

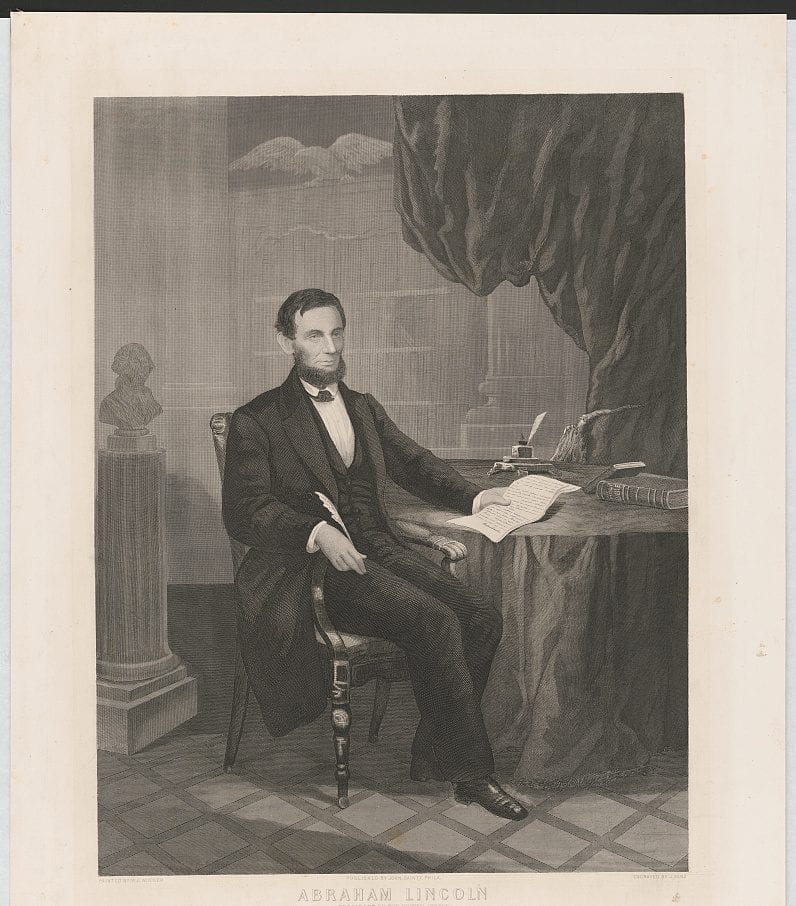

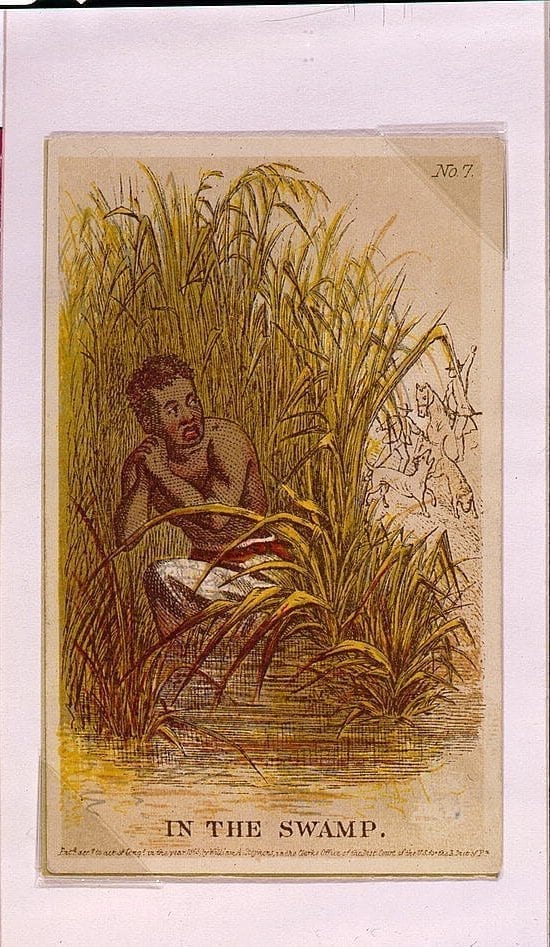

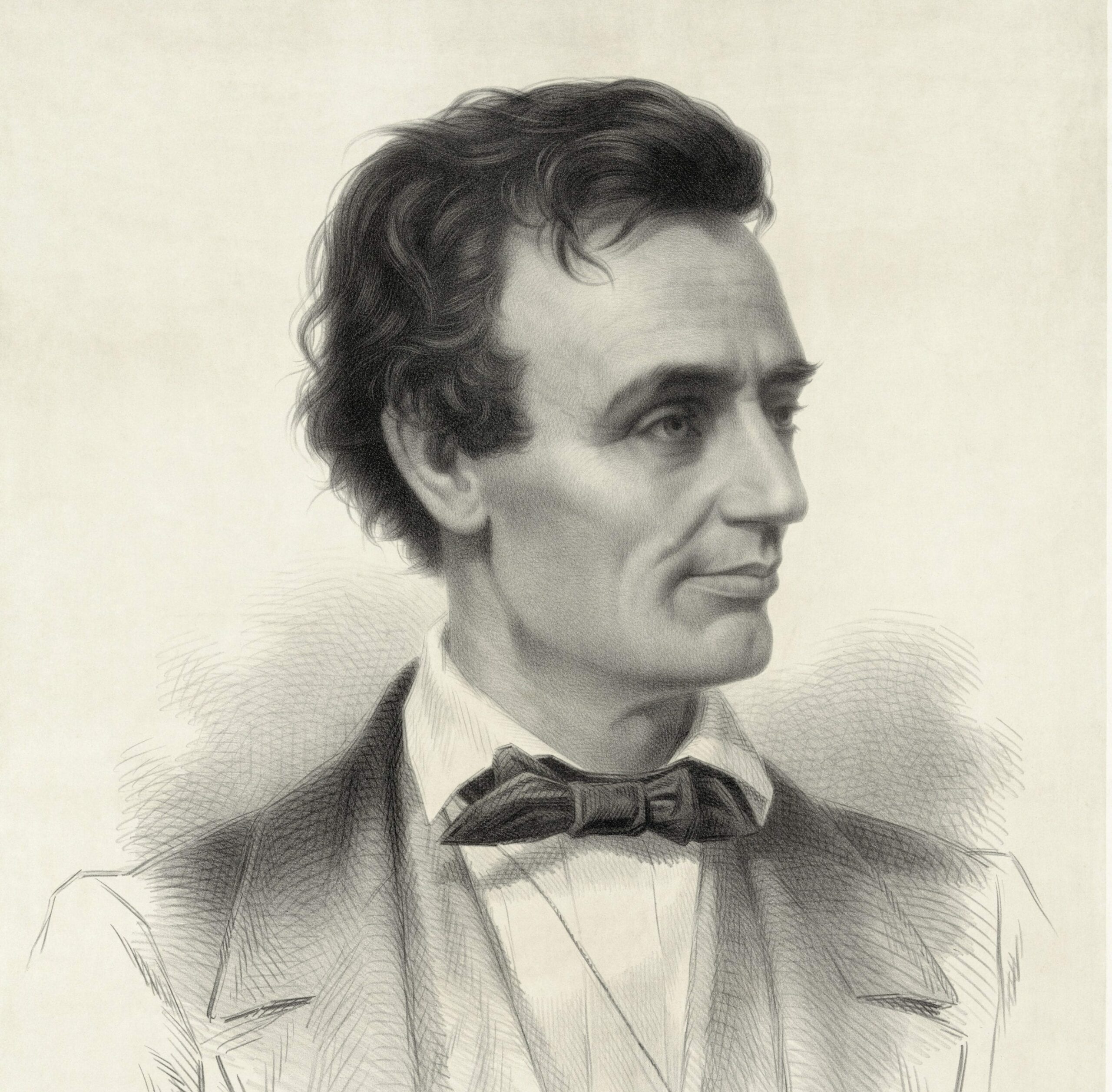

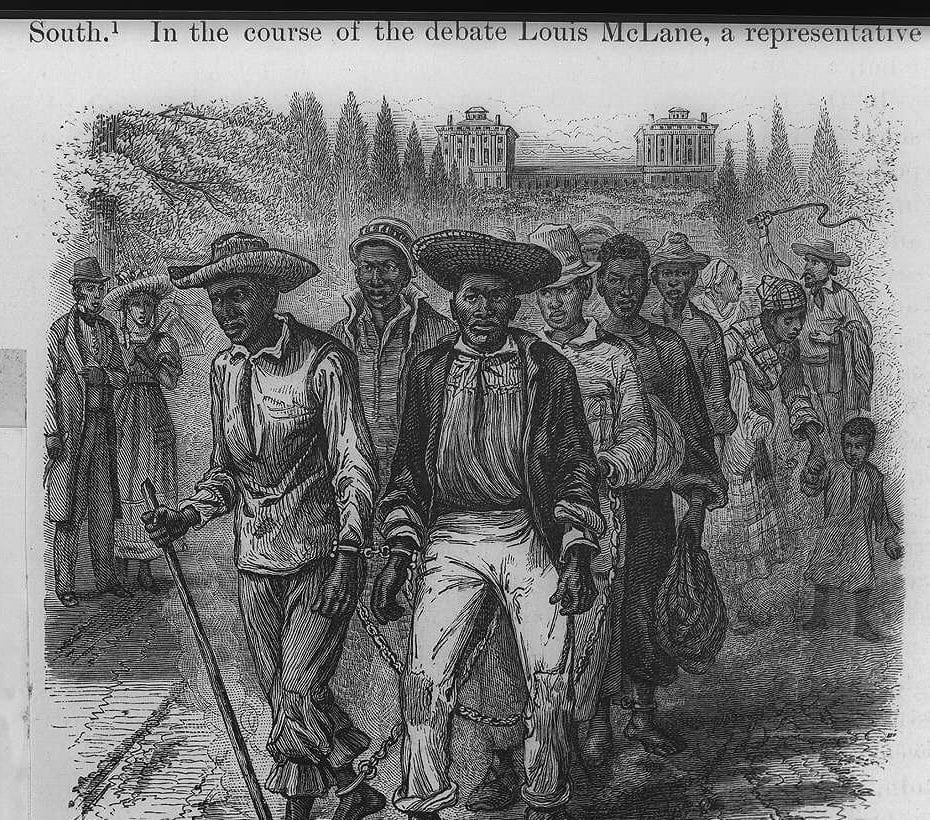

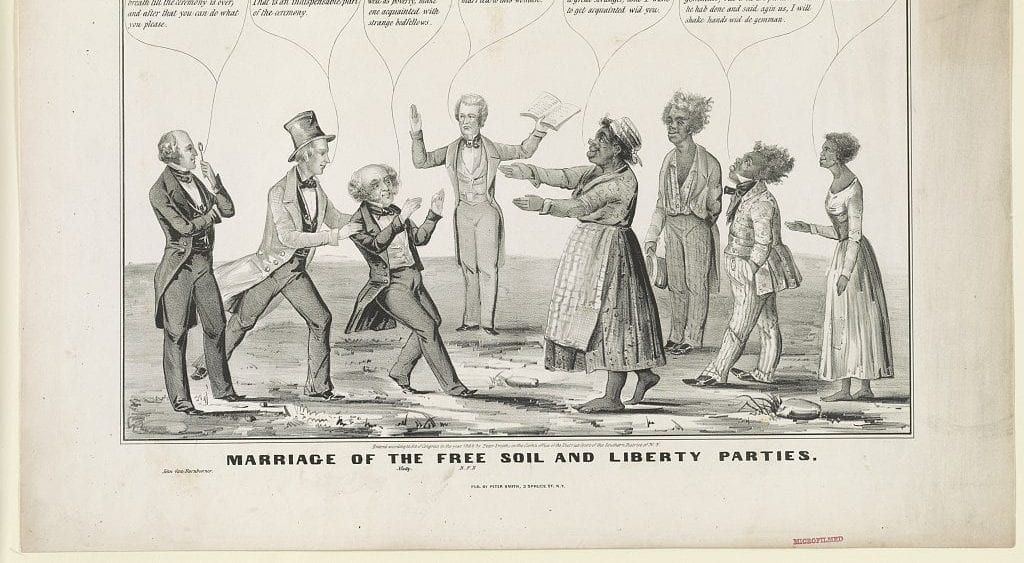

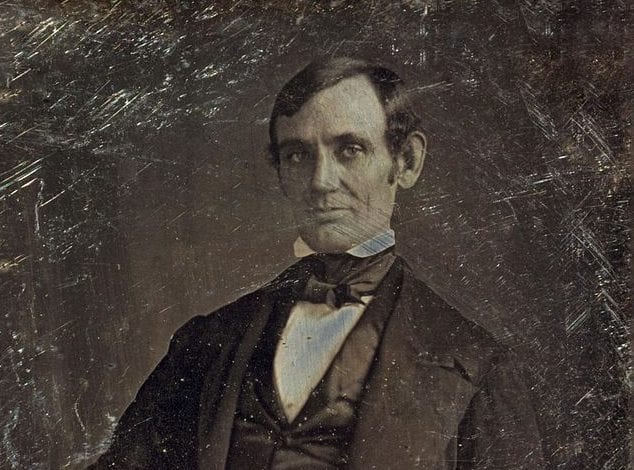

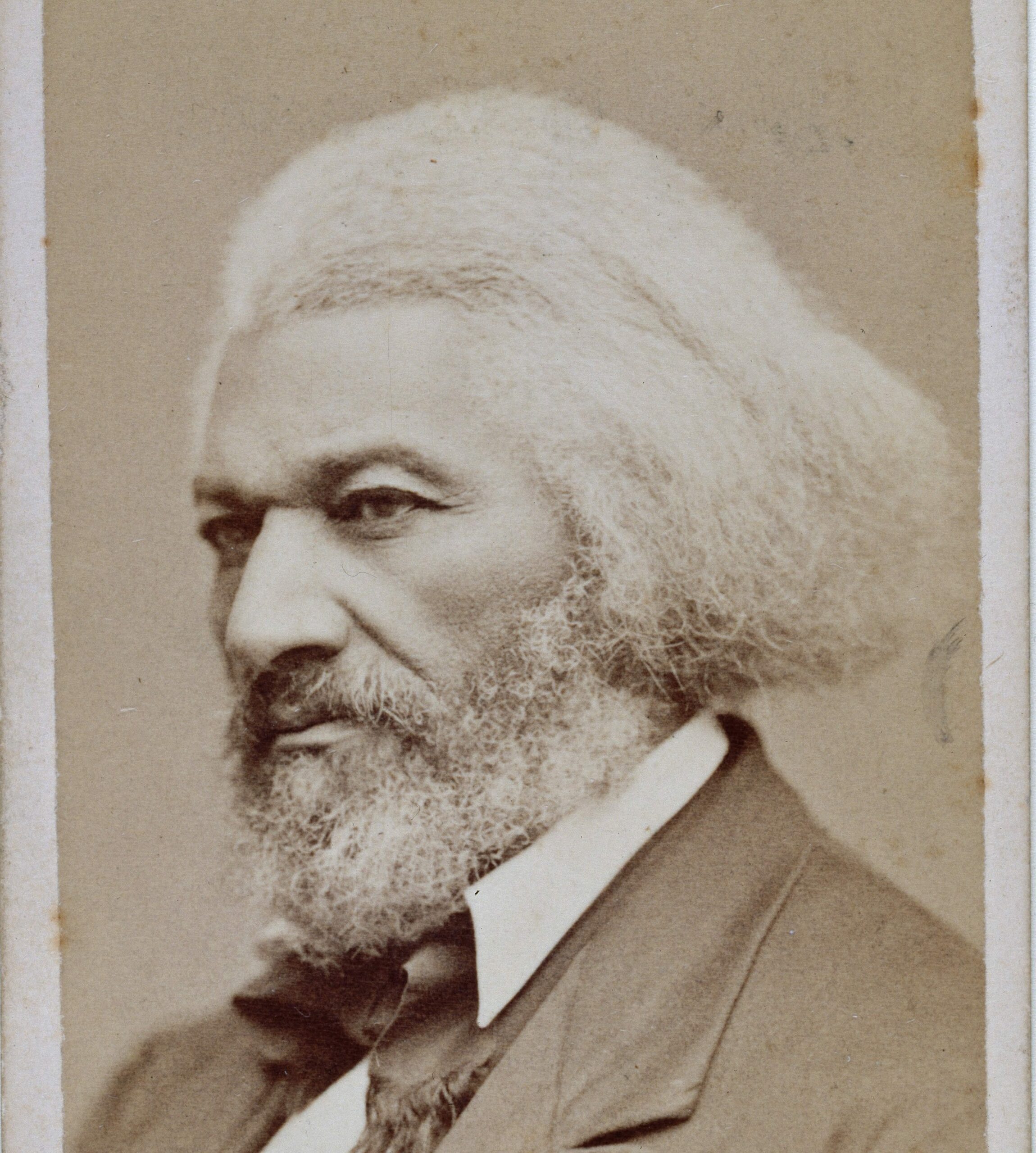

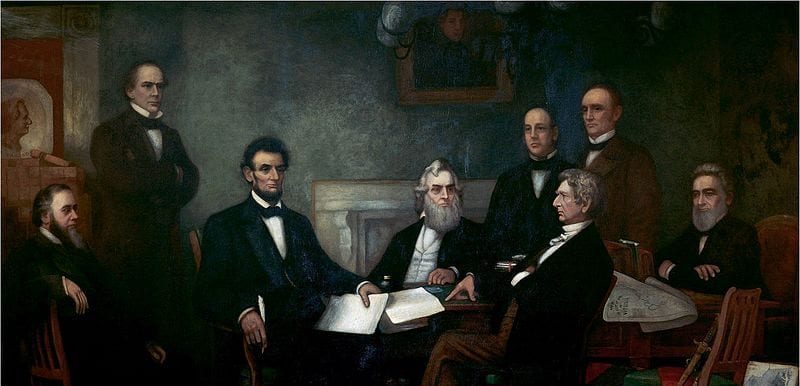

The letter also notes in passing that expatriation of the slaves—removing them from the United States—should accompany their emancipation. This was a standard view in the period leading to the Civil War. Whites felt that the history of antagonism between whites and blacks would make it impossible for them to be fellow-citizens. Blacks who could express a view (“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (1852)) recognized the problem of embittered racial relations, but most often took the view that the United States was as much their country as it was the white man’s. The letter also contains a brief statement of the so-called diffusion theory for ending slavery. This theory held that slavery was more likely to end if it was spread over the United States. As improbable as this may sound to us today, to some in the nineteenth century it seemed true because, as Jefferson explained, it would mean that the cost of emancipation and expatriation would not fall only on the Southern states. Jefferson’s view of the limited power of the Federal government, as he made clear in this letter, persuaded him that it should not be the agent for emancipation and expatriation. Abraham Lincoln later argued that the federal government should play this role, supporting states in their efforts to emancipate and relocate slaves, although acknowledging that the U.S. Constitution gave the states the primary responsibility for dealing with slavery within their borders (Reply to the Dred Scott Decision(1857); First Inaugural Address (1861)).

—Jason W. Stevens

Source: Thomas Jefferson to John Holmes. -04-22, 1820. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib023795/.

I thank you, dear sir, for the copy you have been so kind as to send me of the letter to your constituents on the Missouri question. It is a perfect justification to them. I had for a long time ceased to read newspapers, or pay any attention to public affairs, confident they were in good hands, and content to be a passenger in our bark to the shore from which I am not distant. But this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed, indeed, for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper. I can say, with conscious truth, that there is not a man on earth who would sacrifice more than I would to relieve us from this heavy reproach, in any practicable way. The cession of that kind of property, for so it is misnamed, is a bagatelle[1] which would not cost me a second thought, if, in that way, a general emancipation and expatriation could be effected; and, gradually, and with due sacrifices, I think it might be. But as it is, we have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other. Of one thing I am certain, that as the passage of slaves from one state to another, would not make a slave of a single human being who would not be so without it, so their diffusion over a greater surface would make them individually happier, and proportionally facilitate the accomplishment of their emancipation, by dividing the burthen on a greater number of coadjutors.[2] An abstinence too, from this act of power, would remove the jealousy excited by the undertaking of Congress to regulate the condition of the different descriptions of men composing a state. This certainly is the exclusive right of every state, which nothing in the Constitution has taken from them and given to the general government. Could Congress, for example, say, that the non-freemen of Connecticut shall be freemen, or that they shall not emigrate into any other state?

I regret that I am now to die in the belief, that the useless sacrifice of themselves by the generation of 1776, to acquire self-government and happiness to their country, is to be thrown away by the unwise and unworthy passions of their sons, and that my only consolation is to be, that I live not to weep over it. If they would but dispassionately weigh the blessings they will throw away, against an abstract principle more likely to be effected by union than by scission, they would pause before they would perpetrate this act of suicide on themselves, and of treason against the hopes of the world. To yourself, as the faithful advocate of the Union, I tender the offering of my high esteem and respect.