A Pageantry of Power: Planning Washington’s First Inauguration

This blog post, written by faculty member Sarah Morgan Smith, was first posted on January 19, 2021.

An online resource guide at Library of Congress, U.S. Presidential Inaugurations: “I Do Solemnly Swear…,” showcases the development of the inauguration day ceremonies. For each president, library staff have collected primary materials illustrating what made his inauguration unique. There are drafts of inaugural addresses, descriptions of the ceremonies written by attendees (sometimes by the president himself), and a wide variety of memorabilia, including ceremony tickets and programs, prints, photographs and even sheet music. Each entry also includes a list of historical ‘firsts,’ along with factoids like which Bible the president was sworn in on, the number of inaugural balls held, and so on. A particularly interesting set of documents illustrates the very first presidential inauguration ceremonies, those for George Washington.

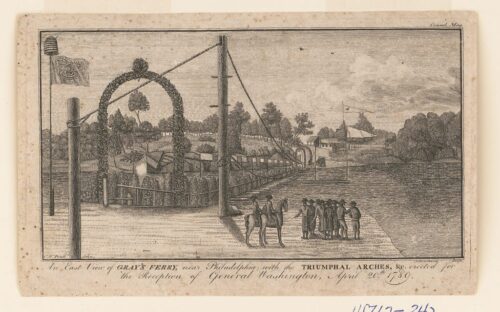

The first Presidential inauguration in American history entailed careful planning, with much behind-the-scenes negotiation. As the first grand public event of the nation under its new Constitution, the inauguration had to strike just the right note. Ceremony was needed, but the event could not be overly solemn, lest it be seen as a royal coronation. Nor could it be merely celebratory, lest it appear too common.

William Maclay, the first United States Senator from Pennsylvania and an inveterate diarist, believed the Senate spent altogether too much time worrying about the niceties of the occasion: “Ceremonies, endless ceremonies, the whole business of the day” (Journal of William McClay, April 25th [1789]). Although a member of the “upper” house, Maclay had very republican tastes and habits. He abhorred those whom he saw applying too aristocratic a veneer over the inauguration ceremonies and, by extension, the new government. Virginians and New Englanders were particularly prone to this vice, Maclay thought, although the “gentlemen of New England” were the worst:

No people in the Union dwell more on trivial distinctions and matters of mere form. They really seem to show a readiness to stand on punctilio and ceremony. A little learning is a dangerous thing (’tis said). May not the same be said of breeding? … Being early used to a ceremonious and reserved behavior, and believing that good manners consists entirely in punctilios, they only add a few more stiffened airs to their deportment, excluding good humor, affability of conversation, and accommodation of temper and sentiment as qualities too vulgar for a gentleman (Journal of William McClay, 28 April 1789).

Vice President John Adams, in particular, irritated Maclay. Adams worried over the formalities, particularly as they related to his (relatively non-existent) role in the forthcoming event. The plan was for Washington to come to the Senate chambers after taking the oath of office. Adams, ever the dramatist, informed the Senate that he was unsure of how to handle himself under such circumstances:

Gentlemen, I feel great difficulty how to act. I am possessed of two separate powers; the one in esse [nature] and the other in posse [power]. I am Vice-President. In this I am nothing, but I may be everything. But I am president also of the Senate. When the President comes into the Senate, what shall I be? I cannot be [president] then. No, gentlemen, I cannot, I cannot. I wish gentlemen to think what I shall be. (Journal of William McClay, April 25)

The Senate, wisely, refrained from attempting to resolve Adams’ identity crisis and moved on to discuss more substantive aspects of the inauguration ceremonies.

Other tense moments marked the planning process. Each highlighted the difficulty of creating in a moment the customs of a new nation. A joint committee, made up of members from the House and Senate, worked out a proposed order of ceremonies. The two houses of Congress then discussed the plan, suggesting amendments. Maclay, a stickler for parliamentary procedure, objected to a motion that the Senators join Washington at a church service following his inauguration. The idea had already been rejected by the joint committee in the course of their sessions. Maclay wrote, “I opposed it as an improper business after it had been in the hands of the Joint Committee and rejected, as I thought this a certain method of creating a dissension between the Houses.” (Journal of William McClay, 27 April) The following day a proposal was made to require state officials to swear allegiance to the new government. Now Maclay worried that the relationship between the federal government and the states would be damaged by the inauguration ceremonies.

Inauguration day dawned at last: “a great, important day,” Maclay wrote, and then implored, “Goddess of etiquette, assist me while I describe it.”

The Vice-President rose in the most solemn manner. … “Gentlemen, I wish for the direction of the Senate. The President will, I suppose, address the Congress. How shall I behave? How shall we receive it? Shall it be standing or sitting?” (Journal of William McClay, 30 April 1789).

In response to Adams’ question, a number of senators began to discuss the behavior of the houses of Parliament when being addressed by the king, and whether, indeed, the new Senate ought to model itself on Britain at all.

Before this question could be resolved, the Clerk from the House of Representatives appeared at the door of the Senate chamber with “a communication.” His appearance vexed the Senate greatly, according to Maclay, for they knew not how to receive him:

A silly kind of resolution of the committee on that business had been laid on the table some days ago. The amount of it was that each House should communicate to the other what and how they chose; it concluded, however, something in this way: That everything should be done with all the propriety that was proper. The question [now] was, Shall this be adopted, that we may know how to receive the Clerk? It was objected [that] this will throw no light on the subject; it will leave you where you are.

Mr. Lee brought the House of Commons before us again. He reprobated the rule; declared that the Clerk should not come within … that the proper mode was for the Sergeant-at-Arms, with the mace on his shoulder, to meet the Clerk at the door and receive his communication; we are not, however, provided for this ceremonious way of doing business, having neither mace nor sergeant …. (Journal of William McClay, 30 April 1789).

Things went on in this vein for some time, with the poor Clerk kept out of the Senate chamber until finally “repeated accounts came [that] the Speaker and Representatives were at the door. Confusion ensued….” Eventually, the members of the House were admitted and sat down with the Senators to await the arrival of the President. After a delay of over an hour, Washington appeared.

The President advanced between the Senate and Representatives, bowing to each. He was placed in the chair by the Vice-President; the Senate with their president on the right, the Speaker and the Representatives on his left. The Vice-President rose and addressed a short sentence to him. The import of it was that he should now take the oath of office as President. … The President was conducted out of the middle window into the gallery, and the oath was administered by the Chancellor. Notice that the business done was communicated to the crowd by proclamation, etc., who gave three cheers, and repeated it on the President’s bowing to them. (Journal of William McClay, 30 April 1789).

Interestingly, administration of the oath of office seems to have been the extent of the public’s involvement in the inauguration ceremonies, for Washington then returned to the Senate chamber where (despite the formally unresolved status of Adams’ earlier question of protocol) all parties took their seats. Washington then stood and addressed the room. To Maclay’s eye, “this great man was agitated and embarrassed more than ever he was by the leveled cannon or pointed musket. He trembled, and several times could scarce make out to read, though it must be supposed he had often read it before.” As he read, Washington fidgeted, holding the speech first in one hand and then the other, moving his free hand into and out of the pocket of his breeches.

When he came to the words “all the world,” he made a flourish with his right hand, which left rather an ungainly impression. I sincerely, for my part, wished all set ceremony in the hands of the dancing-masters, and that this first of men had read off his address in the plainest manner, without ever taking his eyes from the paper, for I felt hurt that he was not first in everything. … (Journal of William McClay, 30 April 1789).

Following Washington’s speech (in accordance with the Senate resolution noted above regarding the inclusion of a church service in the day’s festivities), “there was a grand procession to Saint Paul’s Church, where prayers were said by the Bishop.” Maclay notes that members of the militia stood along one of the streets through which the group traveled, but that appears to have been the extent of the pageantry. That evening, however, “grand fireworks” and illuminations were offered to the public.

The wrangle over ceremonial details was not yet finished, however, for the Senate had to take up the President’s address and consider the proper means of entering it in their journals. Introducing it to the record, Adams referred to the inaugural address as the president’s “most gracious speech.” Maclay spoke up, objecting “I cannot approve of this.” Then,

I looked all around the Senate. Every countenance seemed to wear a blank. The Secretary was going on: I must speak or nobody would. “Mr. President, we have lately had a hard struggle for our liberty against kingly authority. The minds of men are still heated: everything related to that species of government is odious to the people. The words prefixed to the President’s speech are the same that are usually placed before the speech of his Britannic Majesty. I know they will give offense. I consider them as improper. I therefore move that they be struck out, and that it stand simply “address” or “speech,” as may be judged most suitable.” (Journal of William McClay, 1 May 1789).

Adams, predictably, defended his use of the phrase, saying “he was for a dignified and respectable government, and as far as he knew the sentiments of the people they thought as he did.” Maclay—ever the republican—countered “that there had been a revolution in the sentiments of people respecting government equally great as that which had happened in the Government itself.” Americans, he argued, were leery of even the “modes” of monarchy, and already suspicious of the new Constitution with its concentration of power at the federal level. “The enemies of the Constitution had objected to it the facility there would be of transition from it to kingly government and all the trappings and splendor of royalty,” he observed. “If such a thing as this appeared on our minutes, they would not fail to represent it as the first step of the ladder in the ascent to royalty.” (Journal of William McClay, 1 May 1789).

Although Adams remained unconvinced, Maclay won the day: Washington’s address was entered into the minutes with republican simplicity. Pageantry to celebrate the successful launch of the new government was one thing; pomp and circumstance in the day-to-day business of politics, quite another.