Homer Plessy and the Case that made Jim Crow’s Career

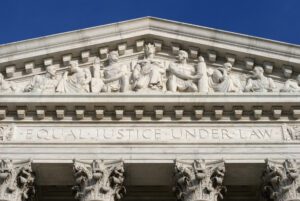

In the 1857 case Dred Scott v. Sandford, the United States Supreme Court argued that under the Constitution and laws of the country, “the Negro … had no rights that the white man was bound to respect.” Almost 100 years later, in Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that racial segregation in public schools was “inherently unequal.” In between these cases, chronologically and figuratively, sits the case of Plessy v. Ferguson.

Plessy v. Ferguson and the 14th Amendment

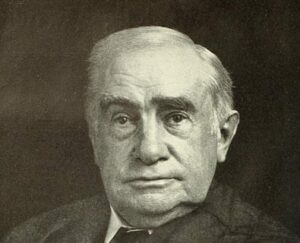

In 1896, the Court ruled in Plessy that segregation in passenger railroad transit was constitutionally permissible if the accommodations for each race were equal. Writing for the majority, Justice Henry Billings Brown “conceded that the 14th Amendment intended to establish absolute equality for the races before the law, but held that separate treatment did not imply the inferiority of African Americans” (www.oyez.org). Justice Brown wrote that state legislatures enjoyed reasonable discretion in applying the racial “customs and traditions” in their states in a manner they believed appropriate for maintaining public order.

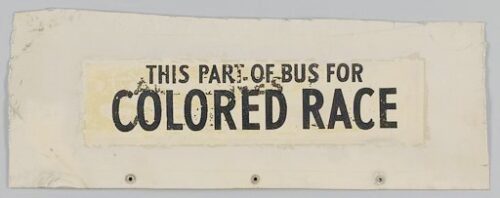

Brown’s attempt to split the baby by acknowledging the 14th Amendment’s call for equality and simultaneously endorsing segregation enabled southern states to enact sweeping legislation mandating segregation in nearly every avenue of life, from separate maternity wards to separate cemeteries. It also linked the names of Homer Adolph Plessy to Dred Scott as symbols of the most infamous Supreme Court cases in United States history. I suspect every U.S. history teacher is familiar with the Plessy decision but as the old radio broadcaster Paul Harvey would say, “stand by for the rest of the story.”

Testing Segregation Laws

Like Rosa Parks in the 1950s, Homer Plessy was a willing participant in the struggle against segregated public accommodations. Plessy helped found a New Orleans, LA, Civil Rights group called, The Citizens Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law. The committee hired a former North Carolina Reconstruction judge, Albion Tourgee, as lead counsel and set about finding the ideal candidate for testing the law. Tourgee wanted a mixed-race plaintiff. He hoped to exploit an oversight in the Louisiana law—the lack of a clear definition of race—which he believed, improperly transferred the state’s police power from state authorities to train conductors. Under the law, the privately employed railroad conductors would ultimately decide who was white and who was black, thus deciding whom to arrest. Homer Plessy, a light-skinned seven-eighths Caucasion and one-eighth African American man, was the perfect candidate for the test case.

After the Louisiana Supreme Court unexpectedly ruled that the separate car law could not apply to interstate travel, Tourgee, Plessy, and the Citizens Committee plotted to test the law on intrastate travel. Plessy purchased a first-class ticket for passage from Covington, LA, to New Orleans on June 7, 1892, boarded the train, and took a seat in a whites only car. When asked to move to a train car designated for “Colored” people, Plessy refused and was arrested.

Unsurprisingly, Plessy lost at the state level. He appealed to the Supreme Court, where the case was heard in April of 1896, and a decision was announced a month later.

The Majority Opinion for Plessy

In the majority opinion, Justice Henry B. Brown dismissed the plaintiff’s argument that the Louisiana law constituted a “badge of slavery,” violating the Thirteenth Amendment. “Laws permitting, and even requiring,” the separation of the races, Justice Brown wrote, do “not necessarily imply the inferiority of either race.” He argued that state legislatures could consider the “customs and traditions” of the local culture and make reasonable accommodations that promoted “the public peace and good order.” The Court ruled that the Louisiana legislature’s discretionary finding that the public peace required segregation was reasonable and that reasonable restrictions did not conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment.

The impact of the Plessy decision is tragic and familiar to U.S. history teachers. Southern historian C. Vann Woodward entitled his book about the era, The Strange Career of Jim Crow. In his book, Woodward argued that the Supreme Court’s Plessy decision stands as a monument to racial segregation and white supremacy in the United States following an era of relatively free interaction between whites and blacks after the Civil War. Tragically, the door did not reopen until later in the 1960s, following passage of the 1964 civil rights act.

Harlan’s Dissent

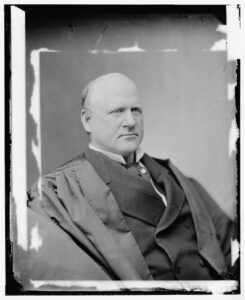

John Marshall Harlan, whose grandson of the same name served on the Supreme Court in the twentieth century, is known as “The Great Dissenter.” His dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson is perhaps best known for the phrase: “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” However, he went much further in attacking the majority opinion. Harlan wrote that the Plessy decision would “prove to be quite as pernicious as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case.” Harlan argued for an expansive view of the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process and equal protection clauses in other cases. He believed that the Fourteenth’s framers intended for that amendment to make the Bill of Rights binding on the states, a view known as incorporation. The Court subsequently adopted Harlan’s opinions in several 20th-century cases and incorporated many, though not all, of the Bill of Rights into the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, making them binding on the states.

What lessons might today’s students learn from studying the background of the Plessy case, in addition to analyzing the reasoning of the Court’s opinion? They may conclude that change moves too slowly and get discouraged, or they may see that change can occur when courageous men—like Homer Plessy and women—like Rosa Parks stand up. When they use the levers of power against unjust laws and work in concert with other like-minded people, as Homer Plessy did in Louisiana, and Rosa Parks did in Montgomery, Alabama.