"Peculiar Recognitions:" Unexplainable Events on the Fourth of July

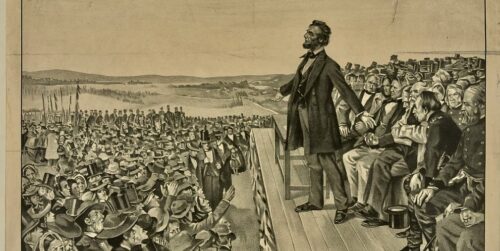

The Civil War had been raging for over two years when Abraham Lincoln began speaking to a large crowd gathered at the Executive Mansion on July 7, 1863. Lincoln thanked them for calling on him and thanked “Almighty God” for two significant victories—Gettysburg and Vicksburg—recently won by the Union army that the crowd had gathered to celebrate. “How long ago is it? —” Lincoln began, “Eighty odd years? — since on the Fourth of July for the first time in the history of the world a nation … declared as a self-evident truth that ‘all men are created equal.'” Citing July 4 as the nation’s birthday, Lincoln thus appeared to begin drafting the brief remarks that he delivered in Gettysburg at the dedication of the national cemetery on that sacred ground in November of 1863. As he refined his theme, the “eighty-odd years” since Americans declared independence became “Four score and seven years ago,” and the Fourth of July became the moment the Founders birthed “a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

The crowd gathering outside the Executive Mansion in 1863 had reason to celebrate. After suffering numerous defeats by the Confederates, the Union army had conquered the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi and forced Lee to retreat from his second and final invasion of the North. Yet only six months before, Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation (January 1, 1863), making the war a war of abolition as well as reunion. Lincoln might have drawn attention to the cause of freedom by referring to the Proclamation in his short speech. Instead, he took the more prudent step of referring to the Declaration’s insistence that “all men are created equal,” allowing his audience to draw their own conclusions about the connection between this affirmation and emancipation. In taking this approach, Lincoln’s short impromptu speech stands in stark contrast to the masterful July 5, 1852 speech by Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” In the words of historian David W. Blight, Douglass composed a “symphony in three movements,” in which he called the Fourth an “American Passover” from which African Americans could draw faith in a future of freedom.

For Lincoln, the Civil War was a test of whether “a nation so conceived and so dedicated could long endure.” He entered office having declared that he “never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.” Unsurprisingly, he returned to the “sentiments of the Declaration” on that emotional evening in July 1863. The nation’s capital had just received confirmation that the Confederate Army defending Vicksburg had surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant on July 4, 1863. News of Vicksburg’s fall—which Lincoln once called the “key to victory” in the war—followed closely on the heels of reports about Gettysburg. That three-day clash ended on July 3, but it was on the Fourth that General Robert E. Lee began his long retreat toward the relative safety of Virginia. The country was electrified by the fact these battlefield triumphs occurred on Independence Day.

In his remarks to the crowd on July 7, Lincoln noted the apparently providential nature of these momentous victories. He also reflected on other coincidental or providential events—depending on one’s views of such occurrences—that happened on the Fourth of July. He specifically cited the deaths of Presidents John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Monroe on the nation’s birthday. Given time, Lincoln might have mentioned other “peculiar recognitions” witnessed on Independence Day. The U.S. Military Academy in West Point first opened its doors on July 4, 1802. On July 4, 1803, President Thomas Jefferson announced that the U.S. had purchased the Louisiana territory from France, thus doubling the nation’s size with the stroke of a pen. Likewise, Lincoln’s call, just days after the shelling of Fort Sumter began the Civil War, for a special session of Congress to begin on July 4, 1861, demonstrated his willingness to use the Fourth’s symbolic significance to pursue his political aim.

Lincoln’s call for a special session of Congress, Jefferson’s Louisiana purchase announcement, and the opening of West Point were events controlled by human hands. Some other notable Independence Day coincidences seem designed by a higher intelligence. Before the Union victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, the most astonishing Fourth of July anniversary event occurred in 1826, with the death of Adams and Jefferson. The two former presidents died not only on the fourth but on the fiftieth anniversary of the Fourth, “the great day of National Jubilee,” in the words of Daniel Webster, astounding the nation. Many Americans viewed the deaths of Adams and Jefferson as what historian Sean Wilentz called “providential omens.” Given their age, the deaths of these Founding Fathers were not unexpected. Jefferson died first, at age 83, early on the afternoon of July 4, 1826. Adams passed several hours later at age 90. His last words, heart-rending although erroneous, were “Thomas Jefferson survives.” In his book, Divided Friends, historian Gordon S. Wood quotes Samuel L. Knapp, editor of the Boston Commercial Gazette, who claimed “the superstitious viewed it as miraculous, and the judicious saw in the event the hand of that Providence, without whose notice not a sparrow falls to the ground.” Indeed, in the minds of many, this was NOT a coincidence. Surely, God called these men home on the 50th anniversary of Independence, “the great day of National Jubilee,” as a token of his approval of their lives and of America’s purpose.

In 1863, Lincoln also suggested that God had a hand in the timing of Jefferson and Adams’ deaths. “The two most distinguished men in the framing and support of the Declaration of Independence were Thomas Jefferson and John Adams,” Lincoln said. “The one penned it, and the other sustained it the most forcibly in debate—the only two of the fifty-five who sustained it being elected President of the United States. Precisely fifty years after they put their hands to the paper, it pleased Almighty God to take both from the stage of action. This was indeed an extraordinary and remarkable event in our history.”

At least one of my former students would agree with Lincoln’s assessment. After I recently posted a blog on one of my favorite American history stories (the disappearance at sea of Aaron Burr’s daughter Theodosia during the War of 1812), Emma, now a teacher herself, commented that her favorite story—of all the stories I told in class—was the deaths of Adams and Jefferson on the 50th anniversary of Independence Day. She recalled that Adams and Jefferson had been friends during the Revolutionary Era, political enemies when contesting the presidency, and friends again when they renewed their correspondence in retirement. Even today, it seems the “peculiar recognition” the Fourth of July brought the deaths of Adams and Jefferson still astonishes Americans. It probably sends many of us checking with Google—Can this really be true?

Other interesting events occurring on July 4:

- 1826 – Stephen Foster – the “Father of American Music” was born

- 1817 – Construction began on the Erie Canal

- 1845 – Texas agreed to be annexed into the United States

- 1872 – Calvin Coolidge was born in Vermont

- 1884 – The Statue of Liberty was presented to the United States by France

- 1934 – Leo Salizard patented the nuclear chain reaction

- 1946 – The Philippines established its independence from the United States

- 1956 – First US U-2 reconnaissance flight over the USSR occurred

- 1997 – The Pathfinder landed on Mars

Related Reading from Teaching American History’s Document database:

Abraham Lincoln, Speech at Independence Hall, February 22, 1861

Abraham Lincoln, Message to Congress in Special Session, July 4, 1861

Abraham Lincoln’s Response to a Serenade on July 7, 1863

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” July 5, 1852