The Long Controversy Over Alger Hiss

When Alger Hiss was convicted of perjury on January 17, 1950, it was, in one sense, the end of a legal drama that began when Whittaker Chambers had named him as a Soviet spy on August 3, 1948. In another sense, though, Hiss’s conviction ended nothing, as the battle over his guilt or innocence had become a major flashpoint in postwar American politics and culture. Even after the Cold War, when declassified U.S. signals intelligence offered extremely compelling evidence that Hiss had in fact been a Soviet asset, bolstering other significant circumstantial evidence, the historical controversy persisted.

The drama began in 1939 when Chambers, a former Communist who had become disillusioned with the party, revealed his activities and those of his associates to a federal government that was preoccupied with the threats of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. One of those Chambers implicated was Hiss, a handsome and well-connected graduate of Johns Hopkins and Harvard Law School working in the State Department. Initially, the charge was overlooked, and Hiss retained supporters among the upper echelons of government. Even when, in 1946, Hiss was forced out of the State Department, Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson arranged for Hiss to take over the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. However, as the wartime alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union increasingly broke down, and the FBI became aware of an extensive Soviet espionage network in the United States, the authorities took Chambers’ allegations more seriously. After Chambers publicly named Hiss, Hiss sued for slander. Chambers then produced documents (including the so-called “Pumpkin Papers” which had famously been hidden in a hollowed out pumpkin) containing confidential State Department information that he claimed—and government analysts would conclude—Hiss had given him. Since the statutory limit for espionage had passed, Hiss was charged with perjury, resulting first in a mistrial before his final conviction seventy years ago today.

Why Controversy Over Hiss Continued

The longevity of the Hiss case is attributable to the fact that it occurred against the backdrop of the Red Scare that was rapidly engulfing the United States. One of the main advocates against Hiss was freshman California Representative Richard Nixon, whose pursuit of Hiss helped propel him to the Senate and then the Vice-Presidency. (Nixon wrote an account of the case against Hiss in his 1962 memoir Six Crises.) Less than a year after Hiss’s conviction, Senator Joseph McCarthy began his own reckless and indiscriminate campaign to root out Communists, a project that became a general hunt for leftists.

For Hiss’s defenders, asserting Hiss’s innocence became a proxy fight against Nixon and McCarthy. Denying the reality of Hiss’s espionage amounted to denying any legitimacy in the postwar pursuit of Soviet spies. To deny Hiss’s innocence, meanwhile, often meant more than just recognizing the reality and the danger of Soviet espionage; it meant using the Hiss case as a bludgeon against the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, which had not acted quickly against Hiss. Hiss’s presence at the Yalta Conference became a significant touchstone in anti-communist discourse. That Hiss’s presence almost certainly had no real impact at Yalta (considering especially that the Soviets had thoroughly bugged the rooms of the American and British delegations and were in a strong position to begin with) was immaterial.

What Finally Convinced Most Skeptics

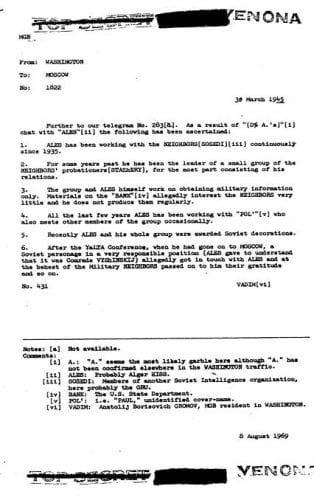

While the fights over Hiss were under way in the late 1940s and 1950s, the strongest evidence of his guilt remained classified, out of fear that revealing the evidence would expose U.S. signals intelligence capabilities to the Soviets. Beginning in 1943, the U.S. Army’s Signal Intelligence Service, the forerunner of today’s National Security Agency, began a project that would later be codenamed Venona. The project began by studying Soviet diplomatic traffic that had been intercepted but unencrypted dating back to 1939, and grew to include ongoing Soviet messages. In one March 1945 message (a facsimile appears below), a Soviet spy discussed a meeting with an agent codenamed ALES:

While not revealing Hiss’s real name, the cable provided details about the agent codenamed ALES, including references to his travels and interactions, that matched the known movements of Hiss. The Venona cables were not released to the public until 1996.

Although occasional challenges still emerge, few today question that Hiss was indeed a spy. The meaning of the Hiss case, however, is more ambiguous. That Hiss was a spy who operated so freely for so many years suggests that the Roosevelt and Truman administrations took far too long to take the threat of espionage from the Soviet Union seriously. However, that the government under-reacted to Chambers’ revelations does not mean that the postwar spy hunt did not produce profound over-reactions and injustices, especially on the part of McCarthy. Perhaps, given the gray areas in which espionage necessarily operates, ambiguity is not only inevitable but appropriate for so famous an espionage case.