War for Union or Abolition? Chapter 15 from Documents and Debates

Many years ago, as I browsed the book section of the North Carolina Museum of History’s gift shop, I stumbled upon “Divided Allegiances: Bertie County in the Civil War” by Gerald W. Thomas. Seeing Bertie County (pronounced Ber-tee) in the title drew my attention. My father, his twin sister, and their three older brothers grew up in Bertie, a sparsely populated northeastern North Carolina county located approximately 90 miles south of Norfolk, VA. My father and his siblings cherished their Bertie County childhoods. All five Tyler siblings told hilarious and occasionally tragic stories about their lives and the neighbors’ lives in their tiny Bertie hamlet – Roxobel. My Uncle Leo announced at family gatherings, “If I can’t be buried in Bertie County, I see no damn good reason to die.”

So I was excited to discover an account of my father’s home county during that catastrophic 19th-century conflict. I grew more excited as I read Gerald Thomas’s preface while standing in the gift shop aisle. Thomas graduated from East Carolina University in 1976, as did I. He moved to Washington, DC, as did I, and he enjoyed hearing tales about Bertie County from older family members, as did I. In his preface, he describes asking his Aunt Nora, his family’s unofficial family historian, why his great-grandfather was not listed as a Confederate soldier by the National Archives. “Old Pap?” exclaimed Aunt Nora. “Old Pap fought with the Yankees!”

I have to buy this book, I thought. I’ll read it and share it with my dad.

Reading Divided Allegiances strengthened my belief that American history is complex – especially the history of the American Civil War. I began challenging my students to sub-divide the broad question every American history teacher confronts in their classroom: What caused the Civil War? I asked them to investigate several separate questions. What caused secession? Why did secession lead to war? Finally, what led individual soldiers to fight?

Regarding secession, the historical record is clear. Slavery was the cause of secession. The evidence can be seen in the Declaration of the Immediate Causes, which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union (January 9, 1861) – Document B in Chapter 15 of Documents and Debates, Volume I. Another clarifying text – Document D in this chapter – is Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens’ “Cornerstone Speech.” If your students need more evidence, ask them to consider the secession ordinance of South Carolina. And they can also consider Stephen F. Hale’s letter to Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin in which he attempted to persuade Kentucky to join the Confederate cause. All these sources make clear that the threat to slavery Southerners perceived “was, somehow, the cause of the war,” as Lincoln says in his Second Inaugural Address.

Seven states made the political decision to secede from the United States – following the election of Abraham Lincoln yet before his inauguration – because they perceived that his election was a threat to the South’s “peculiar institution,” slavery. Four more, including North Carolina, joined the confederacy after the attack on Fort Sumter in April of 1861 led Lincoln to ask for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion.

On the other hand, individuals chose to fight for a wide range of reasons. Some wanted the adventure, or wanted to see another part of the country. Some wanted to see the Union preserved. Some fled an abusive home life or yielded to peer pressure. Others hoped to protect or abolish slavery. A case in point is Bertie County, NC.

Initially, a majority of the county supported North Carolina remaining in the Union. In the presidential election of 1861, Bertie county gave 58% of her vote to pro-Union candidate John Bell. In a special election in February of 1861, Bertie county voters rejected the call for a secession convention in North Carolina by a 3-1 margin. Not until Fort Sumter surrendered, and Lincoln called on North Carolina to supply the Union with troops to put down the rebellion, did North Carolina secede.

When North Carolina seceded, large numbers of Bertie County men flocked to the Confederate banner. Later, when the Union navy captured nearby Plymouth, NC, and the Confederate government initiated conscription, the pendulum swung back in favor of the Union. According to Gerald Thomas’s calculations, from January 1863 to March 1864, “375 Bertie County men (black and white) enlisted in the Union military services while 131 men enlisted in the Confederate army.” Before the war ended, over 800 county men served in Confederate forces only, while 557 served in the Union army only. Sixty-three pugnacious souls fought on both sides! Before the war ended, countless Confederate soldiers deserted and returned to Bertie County, hiding in the county’s woods and swamps to avoid the Confederate Home Guard. It appears that Bertie County men possessed strong independent streaks – they did not want to be coerced into staying in the Union, nor did they wish to be forced into fighting for disunion.

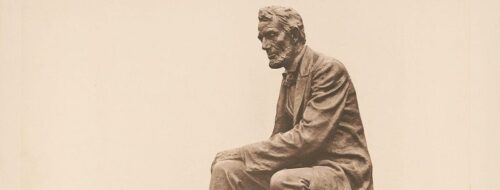

Political leaders made different calculations. In the case of President Lincoln, he entered office declaring that he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists.” As he explained, “I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so” (Document C). As late as 1862, Lincoln insisted in a letter to Horace Greeley that his “paramount object” was to save the Union. He told Greeley that whatever he did or did not do about slavery would be calculated to further his goal of preserving the Union. What changed? Why did he later issue the Emancipation Proclamation freeing enslaved persons in the rebellious states?

I myself would argue that Lincoln’s paramount objective remained preservation of the Union. But he concluded that as long as slavery existed, the threat of secession would remain on the table for slave-holding states. As long as the threat of secession existed the union was vulnerable to dissolution. In Lincoln’s view, secession had to be crushed. Therefore, slavery – the root cause of secession – had to be abolished. Of course, Lincoln also wanted to see slavery abolished; he said so repeatedly throughout his life. Therefore, Lincoln’s actions served dual purposes – the emancipation of enslaved people and the preservation of the Union.

What will your students conclude after reading the documents in this chapter? Will they see slavery as the sole cause of secession? Will they see Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address as threatening the South? Will they see in Stephens’ speech hints of other causes of secession – such as disputes over protective tariffs and federal support for internal improvements?

One reason Teaching American History promotes the use of original sources is because we want to encourage students to think about the complexity of motives that led earlier Americans to make the choices that shaped our history. Few periods in American history capture the complexity of motives like the Civil War. Many Americans continue to debate the motives of those who made crucial personal and political decisions during the war. We can learn from their successes and failures of Civil War decision makers only if we acknowledge that their limitations were not unlike our own. Like us, they stood on the brink of an uncertain future, evaluating their options without knowing the consequences that would follow, for themselves and others. Those who were short-sighted and merely self-interested may remind us to think more carefully, justly and generously. Those who thought carefully and justly may show us our better options.

Documents in this chapter include:

A. Republican National Platform, May 17, 1860

B. Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union, January 9, 1861

C. President Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861

D. Alexander H. Stephens, “Cornerstone Speech,” March 21, 1861

E. Freedom Songs from North and South, 1861–1862

We have provided audio recordings of the chapter’s Introduction, Documents, and Study Questions. These recordings support literacy development for struggling readers and the comprehension of challenging text for all students.

Teaching American History’s We the Teachers blog will feature chapters from our two-volume Documents and Debates with their accompanying audio recordings each month until recordings of all 29 chapters are completed in August of 2021. In today’s post, we feature Volume I, Chapter 15: War for Union or Abolition. On August 24, we will highlight Chapter 29: America and the World, from Volume II of Documents and Debates in American History. We invite you to follow this blog closely, so you can take advantage of this new feature as each recording becomes available.