No study questions

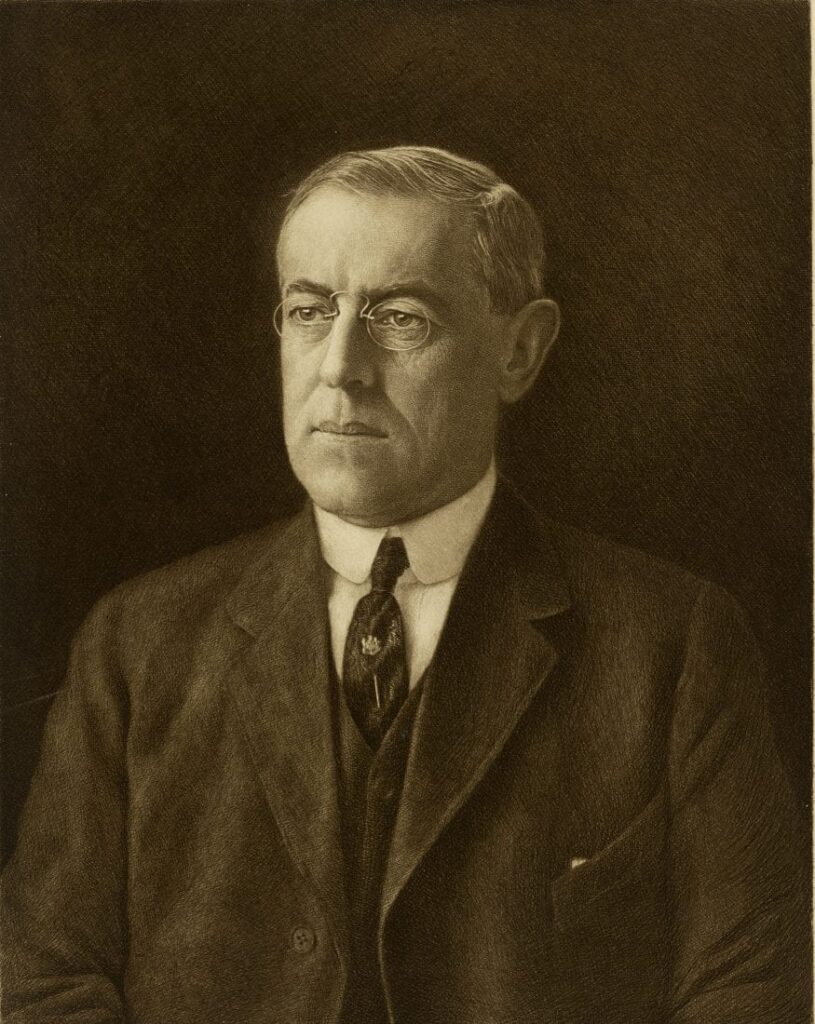

SOURCE: Woodrow Wilson, A Crossroads of Freedom: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Woodrow Wilson. Ed. John Wells Davidson (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1956), 15-37.

. . . The only principle involved in this campaign is: What are we going to do with our economic life? In order to do something new with it you have to have a new attitude with regard to the tariff, and neither of these sections of the Republican party has a new attitude with regard to the tariff. In order to make any change in the life of the United States you have got to have a new attitude towards trusts and monopolies, and neither branch of the Republican party has changed its attitude towards monopoly. If you don't change the fundamental attitude, then you cannot go on the journey of liberty. If you don't face the sun, the sun will not shine in your eyes. You have got to face away from the ideals of monopoly or else you are not bound for the land of freedom.

I have had this image in my mind all morning that the humanistic, the humanitarian part of the third party's program, is a sort of chorus which Mr. Roosevelt is trying to teach the trusts[1] to sing because the fundamental part of that program is that the trusts shall be recognized as a permanent part of our economic order, and that the government shall try to make those trusts the ministers, the instruments, through which the life of this country shall be developed on its industrial side.

Now, everything that touches our lives sooner or later goes back to the industries which sustain our lives. I have often reflected that there was a very human order in the petitions in our Lord's Prayer. For we pray first of all, "Give us this day our daily bread,” knowing that it is useless to pray for spiritual graces on an empty stomach, and that, therefore, the physical part of our life—the industrial part of it, the amount of wages we get, the kind of clothes we wear, the kind of food we can afford to buy—is fundamental to everything else.

Those who administer our physical life, therefore, administer our spiritual life, and if we are going to carry out the fine purposes of that great chorus which the third party is learning to sing almost with religious fervor, then we have got to find out through whom these purposes of humanity are going to be realized. It is a mere enterprise so far as that part is concerned of making the monopolies philanthropic, and I don't want to live under a philanthropy. I don't want to be taken care of by the government, directly or by any instruments through which the government is acting. I want to have right and justice prevail. So far as I am concerned give me the right and justice and I'll undertake to take care of myself.

If you enthrone the trusts as the means of the development of this country under the supervision of the government of the United States, then I shall pray the old Spanish proverb, "God save me from my friends and I will take care of my enemies." Because I want to be saved from these friends. Observe that I said "these friends," for I am ready to admit that a great many men who believe that the development of industry in this country through monopolies is inevitable intend so far as possible to be the friends of the people. But I say to them, "Though you profess to be my friends, you are undertaking the way of friendship which renders it impossible that you should do me the fundamental service that I demand—namely, that I should be free and have the same opportunities that everybody else has."

For I understand it to be the fundamental proposition of American liberty that we do not desire special privilege, because we know special privilege will never comprehend the general welfare, and will therefore never serve it. It is a fundamental spiritual difference between the Democrats and both branches of the Republican party. They are so indoctrinated with the idea that only the big-business interests of this country understand the United States and can make it prosperous that they cannot divorce their thoughts from that obsession. And so they have put the government into the hands of trustees, and Mr. Taft and Mr. Roosevelt are the rival candidates to be president of the board of trustees. They are candidates to serve the people, but they are not candidates to serve them directly. They are candidates to serve them indirectly through the enormous forces already set up, which are so great that there is almost an open question whether the government of the United States with the people back of it is strong enough to overcome and rule them.

We are going to decide on the fifth of November[2] not whether we will overcome and govern them but whether we will attempt to overcome and govern them; for neither branch of the Republican party proposes to set private monopoly aside, and unless we can set private monopoly aside, the enterprise of carrying the government back to the people is impossible. The Democratic platform says that private monopoly is in every case indefensible and intolerable, and I subscribe literally to that statement. I shall stand in any position that I may occupy, shall stand with all the strength that is within me, against every form of monopoly and private control. And I call upon the people of this country to beware of making a choice which will perpetuate private control, and I call upon them particularly in the interest of those fine sentences of the chorus that Mr. Roosevelt is trying to teach the trusts to sing. I believe in that chorus—it stirs my blood. But I do not believe it can be sung under such auspices.

I believe that the time has come when the governments of this country, both state and national, have to set the stage—and set it very minutely and carefully—for the doing of justice to men in every relationship of life. It has been free and easy with us so far; it has been go as you please; it has been every man look out for himself; and we have assumed that in this year when every man is dealing, not with another man, in most cases, but with a body of men whom he has not seen, that the relationships between capital and labor are the same that they always were, and that the relationships of property are the same that they always were.

Let me call your attention to one process of monopoly in this country. Certain monopolies in this country have gained control of the raw material, chiefly in the mines, out of which a great body of manufactures is carried on, and they now discriminate in the sale of that raw material between those who are rivals of the monopoly and those who submit to the monopoly. And we have got to come to a time, ladies and gentlemen, when we shall say to every man who owns the essentials of life that he has got to part with those essentials by sale to every citizen of the United States upon the same terms, or else we shall tie up the resources of this country under private control in such fashion as will make our independent development absolutely impossible.

Then there is another way that monopoly acts. The monopoly that deals in the cruder products which are to be manufactured into the more elaborate manufactures will not sell those crude products except upon the terms of monopoly—that is to say, the people that deal with them will buy exclusively from them. And so again you have the lines of development tied up and the connections of development knotted and fastened so that you can't wrench them apart.

Not only so, but most of the big trusts in this country have been the professed, the avowed, the active opponents and enemies of organized labor. And they only have been the successful opponents of organized labor.

And why has labor organized? Simply because capital organized. And the law of this country does not yet recognize that labor has the same right to organize that capital has. Individuals cannot deal with an organization. Organizations must deal with organizations if there is to be any equality in the terms of dealing. And when I say that monopoly should be broken up in this country, I esteem myself a champion of the laborers of this country because I know that monopoly is stiffening and closing and commanding the market of labor, just as much as it is stiffening and closing the markets for the products which the monopolies produce. Everything is falling into the lines which these gentlemen plan, for if you reduce the number of competitors, you of course eliminate the competition; and there is no competition for labor after you have eliminated this its rival. And, therefore, the prices, wages, can be fixed by the same sort of monopolistic agreements by which the prices of production are fixed, and I don't find the prices of production bearing any particular relationship to the wages paid.

Not long ago, Mr. Taft was, perhaps I may permit myself to say, unfair enough to say that if the Democratic party came into power there would be a long series of rainy years for the working people of this country. Why, gentlemen, has it not begun to rain already for some of them? . . . [T]he laborers in unprotected industry after industry in this country are receiving higher wages than the men in the protected industries, which is not an argument for destroying the tariff, for the Democratic party doesn't stand for that; but it is an argument for displaying humbug and for absolutely refusing to be imposed upon by those who, because they enjoy favors from the government and could hand them on to the workingmen, claim that they do—and they do not. So that something stands between the workingman and the advantage he might get from the protective tariff. Now, that something, neither branch of the Republican party proposes to remove. That something is monopolistic control of the industries of this country—monopolies which have been built up under the government—a shadow, a protection of the special privileges, rather than the general system of the protective tariff of the United States. These gentlemen who profess to be the friends of labor certainly ride their friends to death. They are friends of labor in the same sense that I am a friend of the old mule that I used to own. He was a good servant and would always go under the whip; but the whip was mine, and he had no vote. Now, suppose some privileged power greater than myself should have argued with me about how I should use the whip—that would have been regulated monopoly.

And so it seems to me that every workingman, every thoughtful citizen in the United States, should realize that on the fifth of November next he is going to make a fundamental choice: life under monopoly or not; trust your monopolies to be good to you and benevolent, or see to it that you are good to yourselves; take charge of your own government or hand it over to a permanent board of trustees. Some of these trustees are fine fellows, some of them are very honest men, but I never heard of a body of men who could act successfully and wisely as trustees for a free people. It isn't a question of character; it is a question of the fundamental character of government. You are going to choose the character of your government on the fifth of November; and there is no escape from the alternative. It is easy to make the choice now. Four years from now, I tremble at the difficulties that may lie in the path of the people and, therefore, I am here to commend the Democratic party to you because it alone stands for the fundamental truths of American free life.

It is a very interesting circumstance. Evidence of what I am about to say comes to me by way of corroboration every day in forms that I cannot question. It is a very interesting circumstance that the United States Steel Corporation is behind the third-party program with regard to the regulation of the trusts. Now, I don't say that in order to prejudice you, because I am not here to indict anybody. I am perfectly ready to admit that the officers of the United States Steel Corporation may think that is the best thing for the United States. That is not my point. My point is that these gentlemen have grown up in the atmosphere of the things they themselves have created, and that the law of the United States so far has attempted to destroy the things that they have created, and that they now want a government which will perpetuate the things they have created. You, therefore, have to choose now a government such as the United States Steel Corporation, that is to say, such as the men who promote trusts and monopolies think the United States ought to have, or a government such as we used to have before these gentlemen succeeded in setting up private monopoly. You can tell the character of a thing by the thought of the men who are behind it, not necessarily by the character of the men who are behind it.

As I was coming out West, ladies and gentlemen, a friend of mine who was a westerner said: "Governor, you have been too polite. We western people like punch in our speeches. Now, give it to the other fellows. Don't spare them." But I tell you frankly I am not interested in hitting other people. Why, every man concerned in this great contest is a pigmy as compared with the issues. What difference does Mr. Taft's record make to me? What difference does Mr. Roosevelt's career so far make to me? What difference does my own character, what do my own attainments—whatever they may be—make in the presence of these tremendous issues of life?

I tell you truly I can't afford to think about Mr. Taft or Mr. Roosevelt when I am thinking about the fortunes of the people of the United States. What is punch in a speech compared with that immortal vision that the American people once had of liberty and equality? What are men as compared with the standards of righteousness? What is this generation when measured by the standards that will or will not perpetuate the great polity set up in America?

The only question about these gentlemen and myself is this: After this contest is over, when quiet historians sit down to write the chronicles of the United States, then they will say: "Who were these men who presided over this choice? Who was it that did not see which way America was facing? Who was it that did not utter the warning? Who was it that took the fatal responsibility to say: ‘America has been mistaken. We must follow the old beaten tracks of power. We must give up our hopes of liberty and break our pledges to mankind?’"

[1] “Trust” referred to control by one or more people over a number of firms operating in the same area of the economy, for example steel production or the railroads. A “Trust,” sometimes referred to as a “combination,” came about when shareholders in different corporations transferred their shares to one corporate entity that held them (hence, a “holding company”). The holding company or Trust could be used to establish a monopoly over an area of the economy. For this reason, “trust busting” became part of the U.S. government’s effort to insure free markets in the United States.

[2] The date of the presidential election.

Progressive Party Platform of 1912

November 05, 1912

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.