Introduction

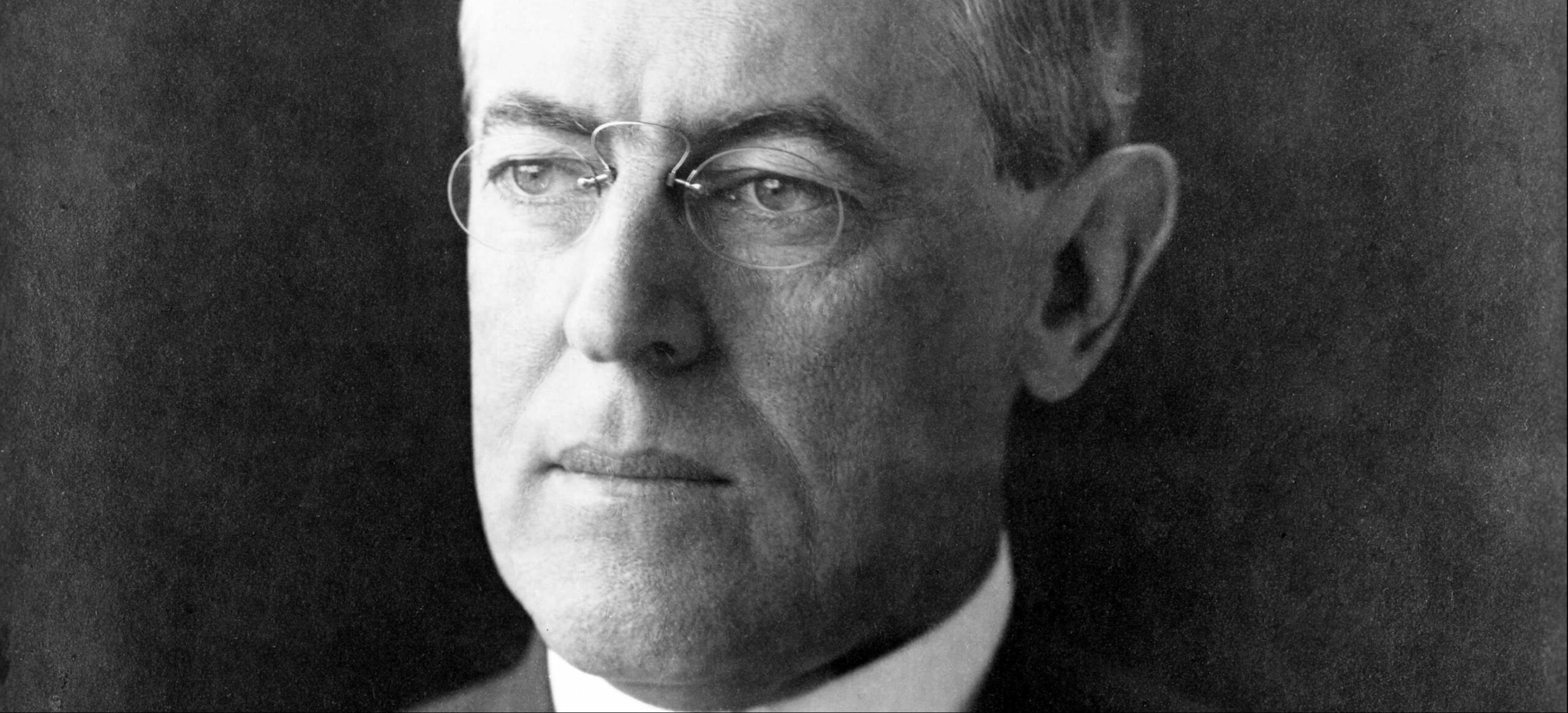

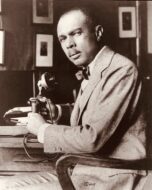

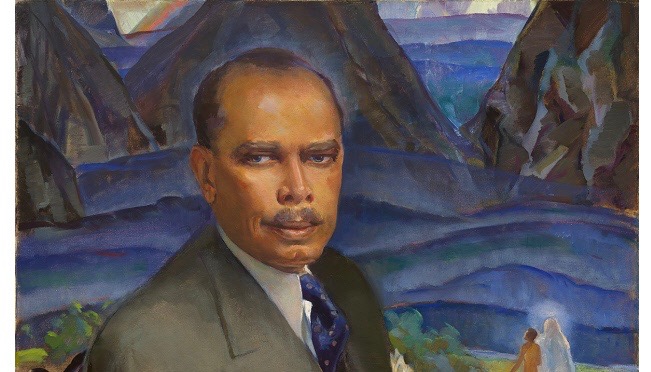

James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) led a remarkably full life as an educator, writer, poet, lyricist, novelist, diplomat and civil rights activist. He is perhaps best remembered for writing the lyrics to “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” (set to music by his brother Rosamond Johnson), often called the Black National Anthem. For ten years (1920–1930) he was the Executive Secretary or chief operating officer of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which he had joined as an organizer in 1916. He was the first African American to hold the position of Executive Secretary.

Johnson published his autobiography, Along This Way, in 1933. In the excerpts below, he commented on the meaning of “social equality” and the differences between the approach of the NAACP and Booker T. Washington. He also described some of his work against lynching. In doing so, he pointed out the harm done by lynching not only to African Americans, but also to white Americans, and thus to America itself. He wrote that after investigating a lynching in Memphis, “the truth flashed over me that in large measure the race question involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul.”

Source: James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson (New York: Da Capo Press, 2000), 311–313, 317–318, 319–321. Copyright 1933 by James Weldon Johnson; copyright renewed 1961 by Grace Nail Johnson. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

. . . When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People announced its platform of equality for the Negro, a great many people were startled.[1] Such a platform, as was to be expected, aroused fierce antagonisms to the organization. It was denounced as radical, revolutionary, subversive; and those at its head were branded as dangerous busybodies or idealistic fanatics. But the most telling attack on the Association was made by those who called it a “social equality” society; for that had the effect of making a good many white friends of the Negro’s cause uneasy, and of placing Negroes themselves on the defensive. This term, “social equality,” is, at the same time, a most concrete and a most elusive obstacle in the Negro’s way. It is never defined; it is shifted to block any path that may be open; it is stretched over whole areas of contacts and activities; it is used to cover and justify every form of restriction, injustice, and brutality practiced against the Negro. The mere term makes cowards of white people and puts Negroes in a dilemma.

Very few, even among the most intelligent Negroes, could find a tenable position on which to base a stand for social among the other equalities demanded. When confronted by the question, they were forced by what they felt to be self-respect, to refrain from taking such a stand. As a matter of truth, self-respect demands that no man admit, even tacitly, that he is unfit to associate with any of his fellow men (and that is aside from whether he wishes to associate with them or not). In the South, policy exacts that any plea made by a Negro—or by a white man, for that matter—for fair treatment to the race, shall be predicated upon a disavowal of “social equality.” Booker T. Washington,[2] in his great Atlanta speech, felt the necessity of declaring, “In all things purely social we can be as separate as the five fingers, and yet one as the hand in all things essential to material progress.” It was this figure of speech, this stroke of consummate diplomacy, that made the whole of his eloquent plea swallowable for Southern throats, and straightway brought him recognition as a statesman. And a fine figure of speech it is, but it does not stand logical analysis. Beyond the ineptitude of its implication that separated fingers (though separated only socially) can constitute an efficient hand, is the fact that it raises an illimitable question: of what do “all things essential to material progress” consist? An elimination of the things deemed “purely social” by Dr. Washington’s white hearers, would have left a very narrow margin, perhaps only a mudsill level[3] of things on which to co-operate like one as the hand.

There ought not to be any intellectual dilemma in this question for a self-respecting Negro. He can, without apology to himself or to anyone else, stand for social equality on any definition of the term not laid down by a madman or an idiot. Certainly, he does not mean that he is watching to sneak or break into somebody’s parlor, or to present himself uninvited for a dinner or a party, or that he has intentions of seizing some Nordic maiden by the hair and dragging her off to be his woman. Certainly, he knows that nothing can compel social intercourse. He sees many Negroes that no force within the race can compel him to invite to his house; and he sees many white people that he would not, under any circumstances, have in his house. But he holds: There should be nothing in law or public opinion to prohibit persons who find that they have congenial tastes and kindred interests in life from associating with each other, if they mutually desire so to do.

But I am fully aware that in writing as I have in the last page or two I have been arguing about “social equality” only from the surfaces of the question. And these surfaces give the whole matter the aspect of a preposterous and absurd farce; especially in the region where “social equality” is talked about most. For, in that region, a white gentleman may not eat with a colored person without the danger of serious loss of social prestige; yet he may sleep with a colored person without incurring the risk of any appreciable damage to his reputation. But behind and under the paradoxes lies a definite significance, a significance so seldom allowed to come into the open that Negroes have not even thought about it; that white women, even those in the South, are, probably, not entirely aware of it; but which every thinking Southern white man understands clearly: “Social equality” signifies a series of far-flung barriers against amalgamation of the two races; except so far as it may come about by white men with colored women.[4] . . .

It was in this period[5] that I rushed to Memphis to make an investigation of the burning alive of Ell Persons, a Negro, charged with being an “ax murderer.” I was in Memphis ten days; I talked with the sheriff, with newspaper men, with a few white citizens, and many colored ones; I read through the Memphis papers covering the period; and nowhere could I find any positive evidence that Ell Persons was the man guilty of the crimes that had been committed. And, yet, without a trial, he was burned alive on the charge. I wrote out my findings, and they were published in a pamphlet that was widely circulated.

On the day I arrived in Memphis, Robert R. Church[6] drove me out to the place where the burning had taken place. A pile of ashes and pieces of charred wood still marked the spot. While the ashes were yet hot, the bones had been scrambled for as souvenirs by the mobs. I reassembled the picture in my mind: a lone Negro in the hands of his accusers, who for the time are no longer human; he is chained to a stake, wood is piled under and around him, and five thousand men and women, women with babies in their arms and women with babies in their wombs, look on with pitiless anticipation, with sadistic satisfaction while he is baptized with gasoline and set afire. The mob disperses, many of them complaining, “They burned him too fast.” I tried to balance the sufferings of the miserable victim against the moral degradation of Memphis, and the truth flashed over me that in large measure the race question involves the saving of black America’s body and white America’s soul. . . .

In the middle of this same summer [1917], on July 2, the colored people of the whole country were appalled by the news of the East St. Louis massacres, a riot in which four hundred thousand dollars’ worth of property was destroyed, nearly six thousand Negroes driven from their homes, hundreds of them killed, some burned in the houses set afire over their heads. This occurrence was the more bitterly ironical because it came when Negro citizens, as others, were being urged to do their bit to “make the world safe for democracy.”[7]

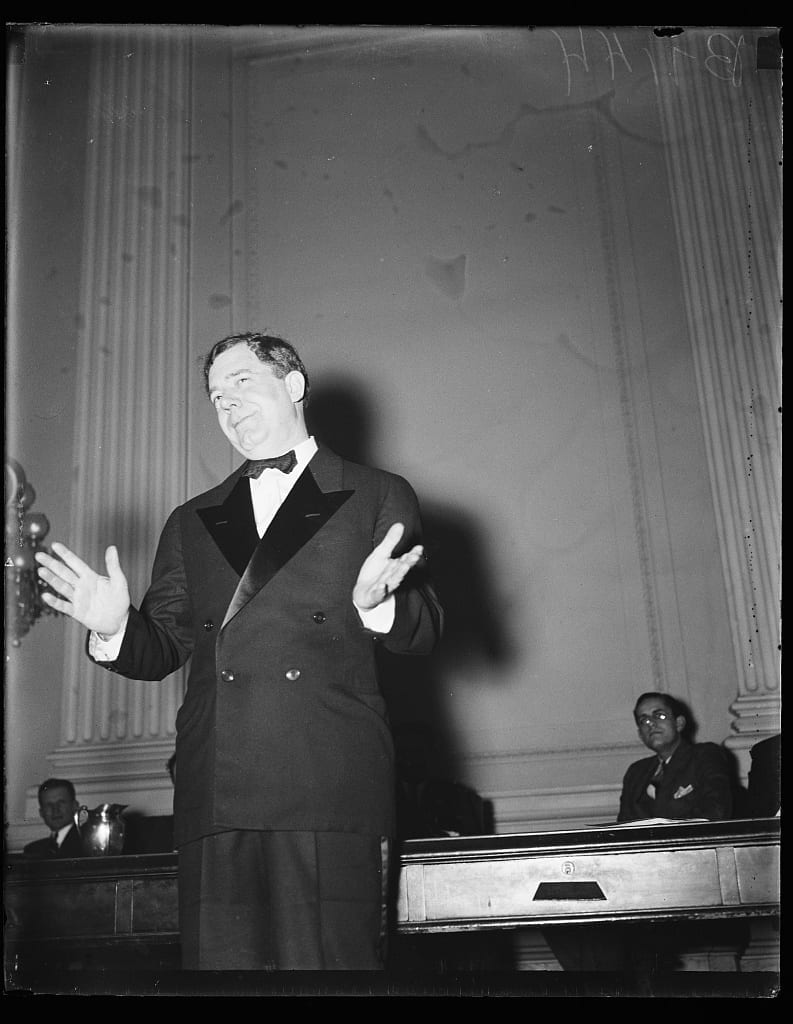

But the reaction to the East St. Louis Massacre was widespread. Congress passed a resolution calling for an investigation. At a hearing before the Committee on Rules of the House of Representatives, Congressman Dyer,[8] of Missouri, among other things, said:

I have visited out there and have interviewed a number of people and talked with a number who saw the murders that were committed. One man. . . now an officer in the United States Army Reserve Corps . . . . said that he saw a part of this killing, and he saw them burning railway cars in yards, which were waiting for transport, filled with interstate commerce. He saw members of the militia of Illinois shoot Negros. He saw policemen of the city of East St. Louis shoot Negroes. He saw this mob go to the homes of these Negroes and nail boards up over the doors and windows and then set fire and burn them up. He saw them take little children out of the arms of their mothers and throw them into the fires and burn them up. He saw the most dastardly and most criminal outrages ever perpetrated in this country, and this is undisputed. And I have talked with others; and my opinion is that over five hundred people were killed on this occasion.

Congressman Rodenberg,[9] of Illinois—East St. Louis is in Illinois—in his remarks before the Committee said:

Now, the plain, unvarnished truth of the matter, as Mr. Joyce told Secretary Baker, is that civil government in East St. Louis completely collapsed at the time of the riot. The conditions there at the time beggar description. It is impossible for any human being to describe the ferocity and brutality of that mob. In one case, for instance, a little ten-year-old boy, whose mother had been shot down, was running around sobbing and looking for his mother, and some member of the mob shot the boy, and before life had passed from his body they picked the little fellow up and threw him in the flames.

Another colored woman with a little two-year-old baby in her arms was trying to protect the child, and they shot her and also shot the child, and threw them in the flames. The horror of that tragedy in East St. Louis can never be described. It weighted me down with a feeling of depression that I did not recover from for weeks. The most sickening things I ever heard of were described in the letters that I received from home giving details of that attack.

As is usual in such occurrences, Negroes were singled out and held legally responsible. The Association secured a staff of lawyers headed by Charles Nagel,[10] Secretary of Commerce under Taft, for their defense, and it also raised a fund for the relief of those who had been made destitute by the riot.

I attended a meeting of the executive committee of our Harlem branch.[11] They were discussing plans to register a protest against the East St. Louis massacre; the plan most favored was a mass meeting at Carnegie Hall. Recalling Mr. Villard’s remarks at the Amenia Conference, I suggested a silent protest parade.[12] The suggestion met with immediate acceptance. It was agreed that the parade should not be made merely an affair of the Association and the Harlem branch, but of the colored citizens of all Greater New York. A large committee, including the pastors of the leading churches and other men and women of influence, was formed, and preparations were gone about with feverish enthusiasm. On Saturday, July 28, nine or ten thousand Negroes marched silently down Fifth Avenue to the sound only of muffled drums. The procession was headed by children, some of them not older than six, dressed in white. These were followed by the women dressed in white, and bringing up the rear came the men in dark clothes. They carried banners; some of which read:

MOTHER, DO LYNCHERS GO TO HEAVEN?

GIVE ME A CHANCE TO LIVE.

TREAT US SO THAT WE MAY LOVE OUR COUNTRY.

PRESIDENT, WHY NOT MAKE AMERICA SAFE FOR DEMOCRACY?

Just ahead of the man who carried the American flag went a streamer that stretched half across the street and bore this inscription:

YOUR HANDS ARE FULL OF BLOOD

The streets of New York have witnessed many strange sights, but, I judge, never one stranger than this; certainly, never one more impressive. The parade moved in silence and was watched in silence. Among the watchers were those with tears in their eyes. Negro Boy Scouts distributed to those lined along the sidewalks printed circulars which stated some of the reasons for the demonstration:

We march because by the Grace of God and the force of truth, the dangerous, hampering walls of prejudice and inhuman injustices must fall.

We march because we want to make impossible a repetition of Waco, Memphis, and East St. Louis,[13] by rousing the conscience of the country and bringing the murderers of our brothers, sisters, and innocent children to justice.

We march because we deem it a crime to be silent in the face of such barbaric acts.

We march because we are thoroughly opposed to Jim Crow Cars, Segregation, Discrimination, Disfranchisement, LYNCHING, and the host of evils that are forced on us. It is time that the Spirit of Christ should be manifested in the making and execution of laws.

We march because we want our children to live in a better land and enjoy fairer conditions than have fallen to our lot.

- 1. Formed in 1909, the corporate charter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (1911) declares its purpose to be “to promote equality of rights and eradicate caste or race prejudice among citizens of the United States; to advance the interest of colored citizens; to secure for them impartial suffrage; and to increase their opportunities for securing justice in the courts, education for their children, employment according to their ability, and complete equality before the law.”

- 2. Atlanta Exposition Address.

- 3. A “mudsill” is the lowest part of a wall resting on the foundation. The term was applied to African Americans by James Henry Hammond, a pro-slavery southerner, in a famous speech in the Senate a few years before the Civil War.

- 4. Emphasis in original.

- 5. Johnson speaks of 1917, when staff at the NAACP were stretched thin. Persons was lynched May 22, 1917.

- 6. Robert R. Church (1885–1952) was a wealthy African American businessman in Memphis. He helped Johnson set up the NAACP chapter in Memphis.

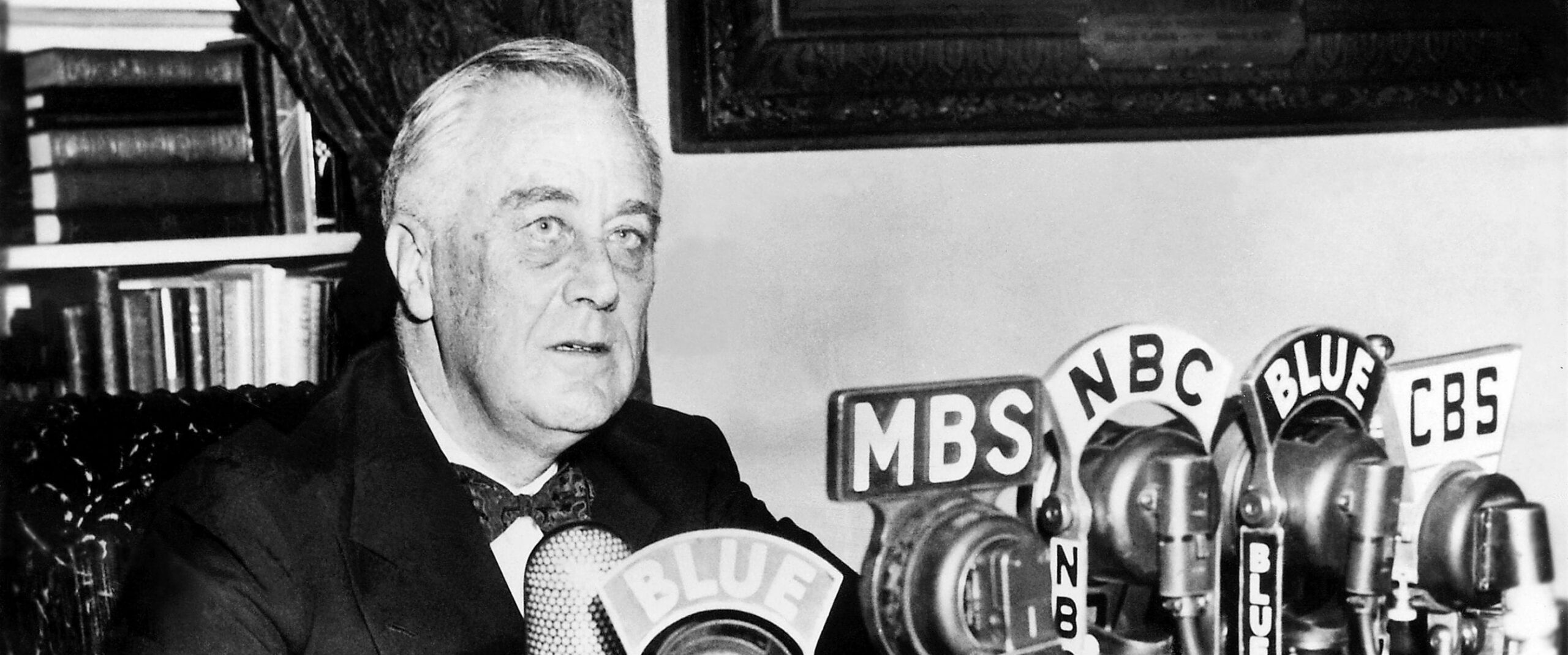

- 7. On April 2, 1917, president Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. In his address to Congress, Wilson explained the purpose of the United States entering into the war by saying, “The world must be made safe for democracy. . . . We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.”

- 8. Leonidas C. Dyer (1871–1957) was a Republican Congressman. In response to the riot in East St. Louis described by Johnson, Dyer sponsored an anti-lynching bill. The House passed the bill in 1922, 1923, and 1924, but it was defeated in the Senate, where it was filibustered.

- 9. William August Rodenberg (1865–1937) was a Republican.

- 10. Charles Nagel (1849–1940) was a Republican lawyer and politician from St. Louis, Missouri.

- 11. Of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

- 12. The Amenia Conference, 1916, held in Amenia, New York, was organized by W. E. B. Du Bois (Documents 30 and 31) and others involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) following the death of Booker T. Washington in 1915. The purpose of the Conference was to unify efforts on behalf of African Americans. Oswald Garrison Villard (1872–1949) was a journalist, newspaper publisher, civil rights activist and founding member of the NAACP.

- 13. Waco, Texas was the scene of the widely publicized lynching of Jesse Washington on May 15, 1916.

Along This Way

December 31, 1933

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.