Introduction

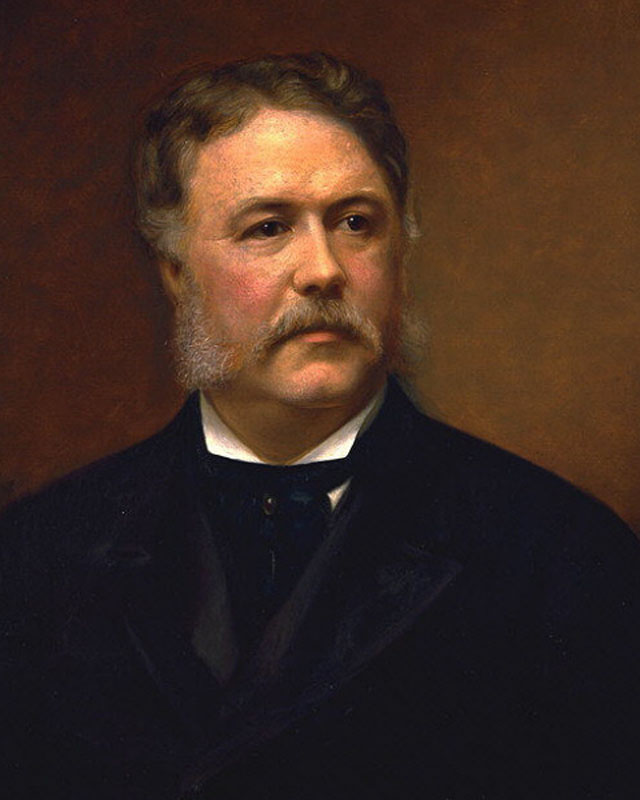

Chester A. Arthur (1829–1886) assumed the office of president upon the death of President James A. Garfield (1831–1881), who was shot by an assassin in July 1881 and died in September of that year. Arthur refers to this event in the opening of his First Annual Message.

The message itself is a useful summary of the late-nineteenth-century positions on western and frontier issues of the Republican Party, since the Civil War the dominant party in American politics. In general, the Republicans sought to Americanize, Christianize, and civilize the West and its inhabitants. The excerpts below focus on law and order, and Native Americans. It is clear from Arthur’s account that with regard to the former, Americans were as much a problem as Native Americans. Both (Americans to the south with Mexico; Native Americans in the north with Canada) posed problems for America’s relations with foreign powers. Physical violence was not the only source of disorder. In a passage not included here, Arthur notes with concern that “the iniquity of polygamy” was spreading in the West as the Mormon population grew and spread to areas outside Utah. The ways Arthur proposed to deal with the West, with both Native Americans and problems of law and order, show the constitutional and legal problems the federal system encountered as the West developed. With regard to the Indians in particular, Arthur’s message manifests the generally held opinion, certainly among Republicans and their allies, that Grant’s peace policy, based on maintaining recognized tribes in territorial reservations, had failed and a new approach was necessary.

Source: Chester A. Arthur, First Annual Message, online, by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/203844.

An appalling calamity has befallen the American people since their chosen representatives last met in the halls where you are now assembled. We might else recall with unalloyed content the rare prosperity with which throughout the year the nation has been blessed. Its harvests have been plenteous; its varied industries have thriven; the health of its people has been preserved; it has maintained with foreign governments the undisturbed relations of amity and peace. For these manifestations of His favor we owe to Him who holds our destiny in His hands the tribute of our grateful devotion. . . .

The surrender of Sitting Bull and his forces upon the Canadian frontier has allayed apprehension,[1] although bodies of British [Canadian] Indians still cross the border in quest of sustenance. Upon this subject a correspondence has been opened which promises an adequate understanding. Our troops have orders to avoid meanwhile all collisions with alien Indians. . . .

The accompanying report of the secretary of war will make known to you the operations of that department for the past year.

He suggests measures for promoting the efficiency of the Army without adding to the number of its officers, and recommends the legislation necessary to increase the number of enlisted men to 30,000, the maximum allowed by law.

This he deems necessary to maintain quietude on our ever-shifting frontier; to preserve peace and suppress disorder and marauding in new settlements; to protect settlers and their property against Indians, and Indians against the encroachments of intruders; and to enable peaceable immigrants to establish homes in the most remote parts of our country.

The Army is now necessarily scattered over such a vast extent of territory that whenever an outbreak occurs reinforcements must be hurried from many quarters, over great distances, and always at heavy cost for transportation of men, horses, wagons, and supplies.

I concur in the recommendations of the secretary for increasing the Army to the strength of 30,000 enlisted men.

It appears by the secretary’s report that in the absence of disturbances on the frontier the troops have been actively employed in collecting the Indians hitherto hostile and locating them on their proper reservations; that Sitting Bull and his adherents are now prisoners at Fort Randall;[2] that the Utes have been moved to their new reservation in Utah; that during the recent outbreak of the Apaches it was necessary to reinforce the garrisons in Arizona by troops withdrawn from New Mexico; and that some of the Apaches are now held prisoners for trial, while some have escaped, and the majority of the tribe are now on their reservation.

There is need of legislation to prevent intrusion upon the lands set apart for the Indians. A large military force, at great expense, is now required to patrol the boundary line between Kansas and the Indian Territory.[3] The only punishment that can at present be inflicted is the forcible removal of the intruder and the imposition of a pecuniary fine, which in most cases it is impossible to collect. There should be a penalty by imprisonment in such cases. . . .

I ask attention to the statements of the secretary of war regarding the requisitions frequently made by the Indian Bureau upon the Subsistence Department of the Army[4] for the casual support of bands and tribes of Indians whose appropriations are exhausted. The War Department should not be left, by reason of inadequate provision for the Indian Bureau, to contribute for the maintenance of Indians. . . .

The acting attorney general also calls attention to the disturbance of the public tranquility during the past year in the territory of Arizona. A band of armed desperadoes known as “Cowboys,” probably numbering from fifty to one hundred men, have been engaged for months in committing acts of lawlessness and brutality which the local authorities have been unable to repress.[5] The depredations of these “Cowboys” have also extended into Mexico, which the marauders reach from the Arizona frontier. With every disposition to meet the exigencies of the case, I am embarrassed by lack of authority to deal with them effectually. The punishment of crimes committed within Arizona should ordinarily, of course, be left to the territorial authorities; but it is worthy consideration whether acts which necessarily tend to embroil the United States with neighboring governments should not be declared crimes against the United States. Some of the incursions alluded to may perhaps be within the scope of the law (U.S. Revised Statutes, sec. 5286) forbidding “military expeditions or enterprises” against friendly states; but in view of the speedy assembling of your body I have preferred to await such legislation as in your wisdom the occasion may seem to demand.

It may perhaps be thought proper to provide that the setting on foot within our own territory of brigandage and armed marauding expeditions against friendly nations and their citizens shall be punishable as an offense against the United States.

I will add that in the event of a request from the territorial government for protection by the United States against “domestic violence” this government would be powerless to render assistance.[6] . . .

It seems to me, too, that whatever views may prevail as to the policy of recent legislation by which the Army has ceased to be a part of the posse comitatus,[7] an exception might well be made for permitting the military to assist the civil territorial authorities in enforcing the laws of the United States. This use of the Army would not seem to be within the alleged evil against which that legislation was aimed. From sparseness of population and other circumstances it is often quite impracticable to summon a civil posse in places where officers of justice require assistance and where a military force is within easy reach.

The report of the secretary of the interior, with accompanying documents, presents an elaborate account of the business of that department. . . .

Prominent among the matters which challenge the attention of Congress at its present session is the management of our Indian affairs. While this question has been a cause of trouble and embarrassment from the infancy of the government, it is but recently that any effort has been made for its solution at once serious, determined, consistent, and promising success.

It has been easier to resort to convenient makeshifts for tiding over temporary difficulties than to grapple with the great permanent problem, and accordingly the easier course has almost invariably been pursued.

It was natural, at a time when the national territory seemed almost illimitable and contained many millions of acres far outside the bounds of civilized settlements, that a policy should have been initiated which more than aught else has been the fruitful source of our Indian complications.

I refer, of course, to the policy of dealing with the various Indian tribes as separate nationalities, of relegating them by treaty stipulations to the occupancy of immense reservations in the West, and of encouraging them to live a savage life, undisturbed by any earnest and well-directed efforts to bring them under the influences of civilization.

The unsatisfactory results which have sprung from this policy are becoming apparent to all.

As the white settlements have crowded the borders of the reservations, the Indians, sometimes contentedly and sometimes against their will, have been transferred to other hunting grounds, from which they have again been dislodged whenever their newfound homes have been desired by the adventurous settlers.

These removals and the frontier collisions by which they have often been preceded have led to frequent and disastrous conflicts between the races.

It is profitless to discuss here which of them has been chiefly responsible for the disturbances whose recital occupies so large a space upon the pages of our history.

We have to deal with the appalling fact that though thousands of lives have been sacrificed and hundreds of millions of dollars expended in the attempt to solve the Indian problem, it has until within the past few years seemed scarcely nearer a solution than it was half a century ago. But the government has of late been cautiously but steadily feeling its way to the adoption of a policy which has already produced gratifying results, and which, in my judgment, is likely, if Congress and the Executive accord in its support, to relieve us ere long from the difficulties which have hitherto beset us.

For the success of the efforts now making to introduce among the Indians the customs and pursuits of civilized life and gradually to absorb them into the mass of our citizens, sharing their rights and holden to their responsibilities, there is imperative need for legislative action.

My suggestions in that regard will be chiefly such as have been already called to the attention of Congress and have received to some extent its consideration.

First. I recommend the passage of an act making the laws of the various states and territories applicable to the Indian reservations within their borders and extending the laws of the state of Arkansas to the portion of the Indian Territory not occupied by the Five Civilized Tribes.[8]

The Indian should receive the protection of the law. He should be allowed to maintain in court his rights of person and property. He has repeatedly begged for this privilege. Its exercise would be very valuable to him in his progress toward civilization.

Second. Of even greater importance is a measure which has been frequently recommended by my predecessors in office,[9] and in furtherance of which several bills have been from time to time introduced in both houses of Congress. The enactment of a general law permitting the allotment in severalty,[10] to such Indians, at least, as desire it, of a reasonable quantity of land secured to them by patent, and for their own protection made inalienable for twenty or twenty-five years, is demanded for their present welfare and their permanent advancement.

In return for such considerate action on the part of the government, there is reason to believe that the Indians in large numbers would be persuaded to sever their tribal relations and to engage at once in agricultural pursuits. Many of them realize the fact that their hunting days are over and that it is now for their best interests to conform their manner of life to the new order of things. By no greater inducement than the assurance of permanent title to the soil can they be led to engage in the occupation of tilling it.

The well-attested reports of their increasing interest in husbandry justify the hope and belief that the enactment of such a statute as I recommend would be at once attended with gratifying results. A resort to the allotment system would have a direct and powerful influence in dissolving the tribal bond, which is so prominent a feature of savage life, and which tends so strongly to perpetuate it.

Third. I advise a liberal appropriation for the support of Indian schools, because of my confident belief that such a course is consistent with the wisest economy.

Even among the most uncultivated Indian tribes there is reported to be a general and urgent desire on the part of the chiefs and older members for the education of their children. It is unfortunate, in view of this fact, that during the past year the means which have been at the command of the Interior Department for the purpose of Indian instruction have proved to be utterly inadequate.

The success of the schools which are in operation at Hampton, Carlisle, and Forest Grove[11] should not only encourage a more generous provision for the support of those institutions, but should prompt the establishment of others of a similar character.

They are doubtless much more potent for good than the day schools upon the reservation, as the pupils are altogether separated from the surroundings of savage life and brought into constant contact with civilization.

There are many other phases of this subject which are of great interest, but which cannot be included within the becoming limits of this communication. They are discussed ably in the reports of the secretary of the interior and the commissioner of Indian Affairs. . . .

Although our system of government does not contemplate that the nation should provide or support a system for the education of our people, no measures calculated to promote that general intelligence and virtue upon which the perpetuity of our institutions so greatly depends have ever been regarded with indifference by Congress or the Executive.

A large portion of the public domain has been from time to time devoted to the promotion of education.[12]

There is now a special reason why, by setting apart the proceeds of its sales of public lands or by some other course, the government should aid the work of education. Many who now exercise the right of suffrage are unable to read the ballot which they cast. Upon many who had just emerged from a condition of slavery were suddenly devolved the responsibilities of citizenship in that portion of the country most impoverished by war. I have been pleased to learn from the report of the commissioner of education that there has lately been a commendable increase of interest and effort for their instruction; but all that can be done by local legislation and private generosity should be supplemented by such aid as can be constitutionally afforded by the national government. . . .

Deeply impressed with the gravity of the responsibilities which have so unexpectedly devolved upon me, it will be my constant purpose to cooperate with you in such measures as will promote the glory of the country and the prosperity of its people.

- 1. Sitting Bull was a Lakota chief who, unlike Red Cloud, did not accept life on a reservation. He was a principal leader of the Indian bands that destroyed the 7th Cavalry, commanded by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer (1839– 1876), at the Battle of the Little Bighorn (1876). Subsequently, he and his followers fled to Canada, returning to the United States to surrender in 1881.

- 2. Located in South Dakota in the eastern part of the state near the border with Nebraska.

- 3. In the current state of Oklahoma

- 4. The department that supplies the Army with food and other necessary materials.

- 5. The “Cowboys” were a gang of thieves and cattle rustlers who often stole cattle in Mexico and then sold them in the United States. Ike Clanton, one of those who fought Wyatt Earp at the OK Corral, was a member of the “Cowboys.”

- 6. Arthur believed that a federal law had to give him the authority to aid territories, because the Constitution authorizes the federal government only to aid states (Article IV, section 4) when threatened by domestic violence.

- 7. Dissatisfaction with the Army’s role in policing the South during Reconstruction led Congress to pass the Posse Comitatus Act in 1878. The law limits the authority of the federal government to enforce domestic law by using the Army. The other U.S. armed services abide by its provisions.

- 8. The Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole tribes. They were removed from the southeastern United States to Indian Territory in what is now the state of Oklahoma. These tribes were agricultural, had centralized government, owned land as individuals, engaged in commerce, and intermarried with other Americans. Many were Christian. Like other southerners, some ran plantations and owned African American slaves before their removal.

- 9. See, for example, Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs

- 10. "Severalty” means that individual Native Americans, rather than the tribe, would own land.

- 11. All three were boarding schools. The school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, opened in 1878. Hampton Institute, originally a school for freed slaves and African Americans, began accepting Native Americans in 1878. The Chemewa School, founded in 1880 in Forest Grove, Oregon, moved to Salem, Oregon, in 1884. It continues to operate.

- 12. See, The Northwest Ordinance

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.