No related resources

Introduction

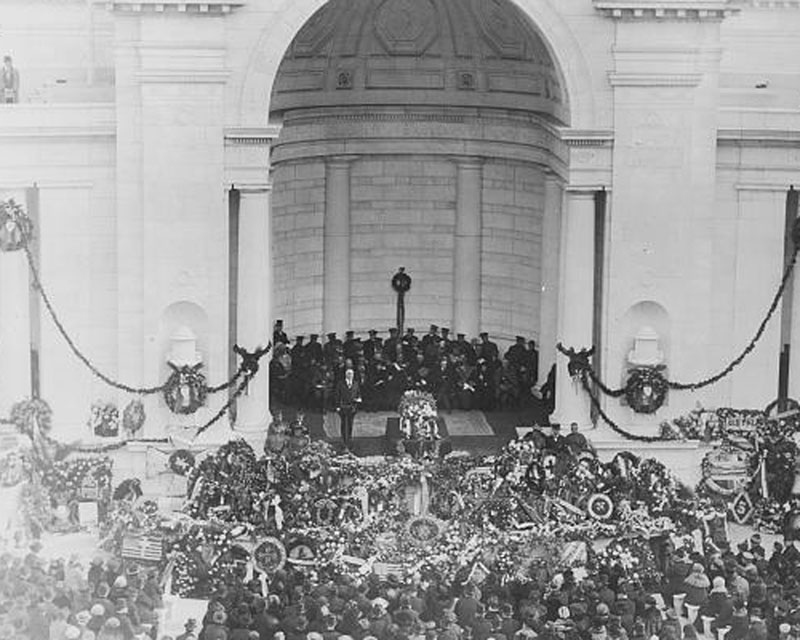

On the third anniversary of the Armistice, one unidentified American soldier was laid to rest in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The tomb stood as a symbolic gravesite for the American servicemen killed in World War I whose remains could not be identified. Thousands paid their respects while the casket lay in state at the Capitol Rotunda. When the remains were transported to the burial site in Arlington National Cemetery, crowds lined the streets to watch a procession that included President Warren G. Harding (1865–1923), the entire Congress and Supreme Court, state governors, foreign dignitaries, and an ailing Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), who rode in a horse-drawn carriage.

Harding’s dedication speech looked to the past and the future. He recalled the war’s unprecedented destruction, hoping to parlay those memories into public support for the Washington Naval Disarmament Conference, which began the next day. Three months of negotiations ultimately resulted in disarmament agreements that limited naval arms and battleships among the world’s leading naval powers, including Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States. These nations also pledged to respect existing Pacific possessions and the Open-Door policy in China favored by the United States.

Americans soon fractured on the meaning assigned to the Unknown Soldier. Was the tomb a monument to victory, patriotism, or pacifism? Literary parodies challenged the general assumption that the Unknown Soldier was a white, Protestant male. James Weldon Johnson’s 1930 poem “Saint Peter Relates an Incident of the Resurrection Day,” for instance, imagined the public’s outrage upon learning that the gravesite contained an African American.

Address of the President of the United States at the Burial of an Unknown American Soldier, Arlington Cemetery, November 11, 1921 (Government Printing Office, 1921). Available at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/loc.ark:/13960/t8nc6t24q.

Mr. Secretary of War1 and Ladies and Gentlemen:

We are met today to pay the impersonal tribute. The name of him whose body lies before us took flight with his imperishable soul. We know not whence he came, but only that his death marks him with the everlasting glory of an American dying for his country.

He might have come from any one of millions of American homes. Some mother gave him in her love and tenderness, and with him her most cherished hopes. Hundreds of mothers are wondering today, finding a touch of solace in the possibility that the nation bows in grief over the body of one she bore to live and die, if need be, for the Republic. If we give rein to fancy, a score of sympathetic chords are touched, for in this body there once glowed the soul of an American, with the aspirations and ambitions of a citizen who cherished life and its opportunities. He may have been a native or an adopted son; that matters little, because they glorified the same loyalty, they sacrificed alike.

We do not know his station in life, because from every station came the patriotic response of the five millions.2 I recall the days of creating armies, and the departing of caravels3 which braved the murderous seas to reach the battle lines for maintained nationality and preserved civilization. The service flag4 marked mansion and cottage alike, and riches were common to all homes in the consciousness of service to country.

We do not know the eminence of his birth, but we do know the glory of his death. He died for his country, and greater devotion hath no man than this. He died unquestioning, uncomplaining, with faith in his heart and hope on his lips, that his country should triumph and its civilization survive. As a typical soldier of this representative democracy, he fought and died, believing in the indisputable justice of his country’s cause. Conscious of the world’s upheaval, appraising the magnitude of a war the like of which had never horrified humanity before, perhaps he believed his to be a service destined to change the tide of human affairs.

In the death gloom of gas, the bursting of shells and rain of bullets, men face more intimately the great God over all, their souls are aflame, and consciousness expands and hearts are searched. With the din of battle, the glow of conflict, and the supreme trial of courage, come involuntarily the hurried appraisal of life and the contemplation of death’s great mystery. On the threshold of eternity, many a soldier, I can well believe, wondered how his ebbing blood would color the stream of human life, flowing on after his sacrifice. His patriotism was none less if he craved more than triumph of country; rather, it was greater if he hoped for a victory for all human kind. Indeed, I revere that citizen whose confidence in the righteousness of his country inspired belief that its triumph is the victory of humanity.

This American soldier went forth to battle with no hatred for any people in the world, but hating war and hating the purpose of every war for conquest. He cherished our national rights, and abhorred the threat of armed domination; and in the maelstrom of destruction and suffering and death he fired his shot for liberation of the captive conscience of the world. In advancing toward his objective was somewhere a thought of a world awakened; and we are here to testify undying gratitude and reverence for that thought of a wider freedom.

On such an occasion as this, amid such a scene, our thoughts alternate between defenders living and defenders dead. A grateful Republic will be worthy of them both. Our part is to atone for the losses of heroic dead by making a better Republic for the living.

Sleeping in these hallowed grounds are thousands of Americans who have given their blood for the baptism of freedom and its maintenance, armed exponents of the nation’s conscience. It is better and nobler for their deeds. Burial here is rather more than a sign of the government’s favor, it is a suggestion of a tomb in the heart of the nation, sorrowing for its noble dead.

Today’s ceremonies proclaim that the hero unknown is not unhonored. We gather him to the nation’s breast, within the shadow of the Capitol, of the towering shaft that honors Washington, the great father, and of the exquisite monument to Lincoln, the martyred savior. Here the inspirations of yesterday and the conscience of today forever unite to make the Republic worthy of his death for flag and country.

Ours are lofty resolutions today, as with tribute to the dead we consecrate ourselves to a better order for the living. With all my heart, I wish we might say to the defenders who survive, to mothers who sorrow, to widows and children who mourn, that no such sacrifice shall be asked again.

It was my fortune recently to see a demonstration of modern warfare. It is no longer a conflict in chivalry, no more a test of militant manhood. It is only cruel, deliberate, scientific destruction. There was no contending enemy, only the theoretical defense of a hypothetic objective. But the attack was made with all the relentless methods of modern destruction. There was the rain of ruin from the aircraft, the thunder of artillery, followed by the unspeakable devastation wrought by bursting shells; there were mortars belching their bombs of desolation; machine guns concentrating their leaden storms; there was the infantry, advancing, firing, and falling—like men with souls sacrificing for the decision. The flying missiles were revealed by illuminating tracers, so that we could note their flight and appraise their deadliness. The air was streaked with tiny flames marking the flight of massed destruction; while the effectiveness of the theoretical defense was impressed by the simulation of dead and wounded among those going forward, undaunted and unheeding. As this panorama of unutterable destruction visualized the horrors of modern conflict, there grew on me the sense of the failure of a civilization which can leave its problems to such cruel arbitrament. Surely no one in authority, with human attributes and a full appraisal of the patriotic loyalty of his countrymen, could ask the manhood of kingdom, empire, or republic to make such sacrifice until all reason had failed, until appeal to justice through understanding had been denied, until every effort of love and consideration for fellow men had been exhausted, until freedom itself and inviolate honor had been brutally threatened.

I speak not as a pacifist fearing war, but as one who loves justice and hates war. I speak as one who believes the highest function of government is to give its citizens the security of peace, the opportunity to achieve, and the pursuit of happiness.

The loftiest tribute we can bestow today—the heroically earned tribute—fashioned in deliberate conviction, out of unclouded thought, neither shadowed by remorse nor made vain by fancies, is the commitment of this Republic to an advancement never made before. If American achievement is a cherished pride at home, if our unselfishness among nations is all we wish it to be, and ours is a helpful example in the world, then let us give of our influence and strength, yea, of our aspirations and convictions, to put mankind on a little higher plane, exulting and exalting, with war’s distressing and depressing tragedies barred from the stage of righteous civilization.

There have been a thousand defenses justly and patriotically made; a thousand offenses which reason and righteousness ought to have stayed. Let us beseech all men to join us in seeking the rule under which reason and righteousness shall prevail.

Standing today on hallowed ground, conscious that all America has halted to share in the tribute of heart and mind and soul to this fellow American, and knowing that the world is noting this expression of the Republic’s mindfulness, it is fitting to say that his sacrifice, and that of the millions dead, shall not be in vain. There must be, there shall be, the commanding voice of a conscious civilization against armed warfare.

As we return this poor clay to its mother soil, garlanded by love and covered with the decorations5 that only nations can bestow, I can sense the prayers of our people, of all peoples, that this Armistice Day shall mark the beginning of a new and lasting era of peace on earth, good will among men. Let me join in that prayer.

Our Father who are in heaven, hallowed be Thy name. Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil, for Thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, forever. Amen.

- 1. Secretary of War Harry L. Davis (1878–1950).

- 2. Overall, U.S. forces during the war numbered 4.4 million.

- 3. Hoover’s use of the term “caravel” for ships was symbolic rather than literal. A caravel was a long-voyage, highly maneuverable ship employed by the Spanish and Portuguese in the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries to explore West Africa and the Atlantic Ocean.

- 4. During the war, many American households displayed a service flag with a blue star to represent each family member in the armed service. The star changed to gold if the relative died.

- 5. The Unknown Soldier was buried with the Medal of Honor and the Distinguished Service Cross, along with military decorations from other nations, including the Victoria Cross from Great Britain.

Annual Message to Congress (1921)

December 06, 1921

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.