Introduction

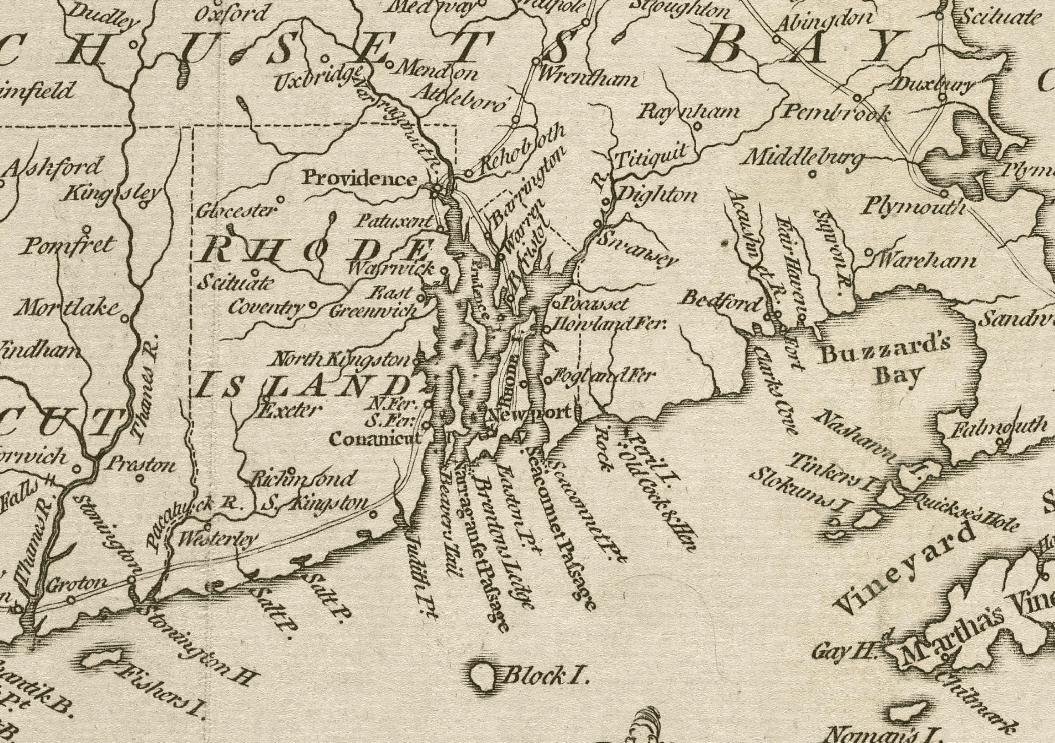

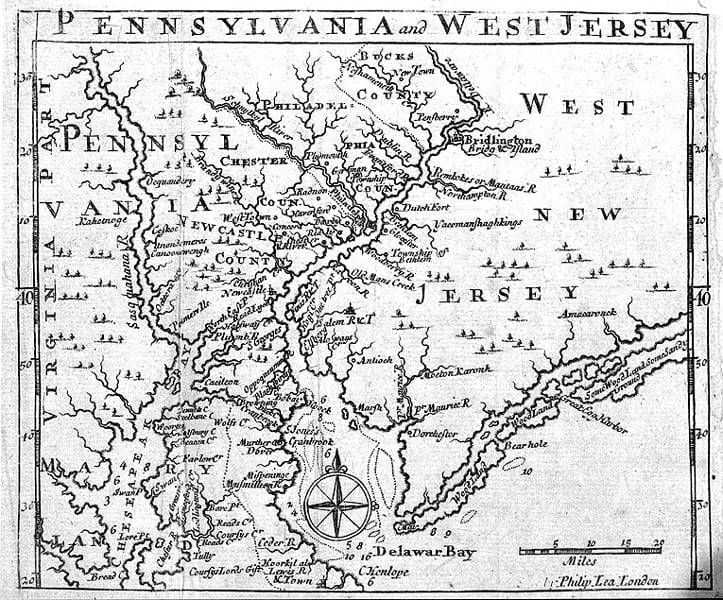

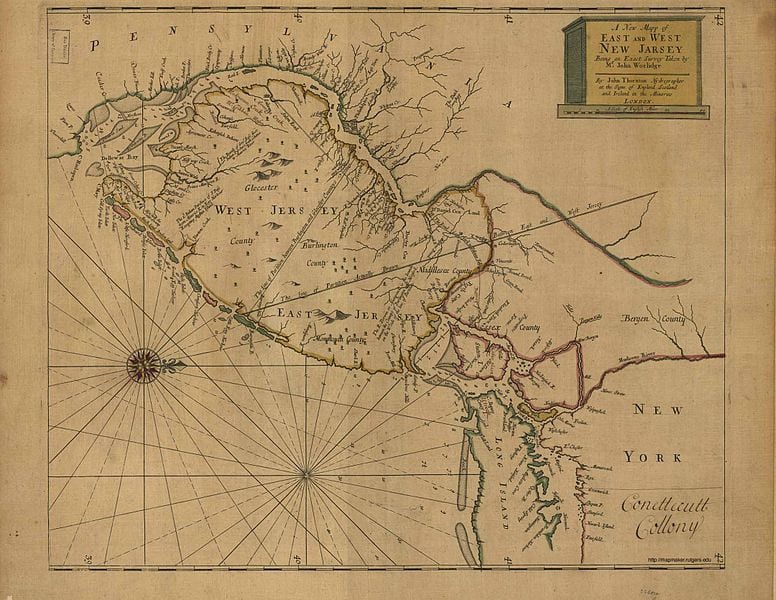

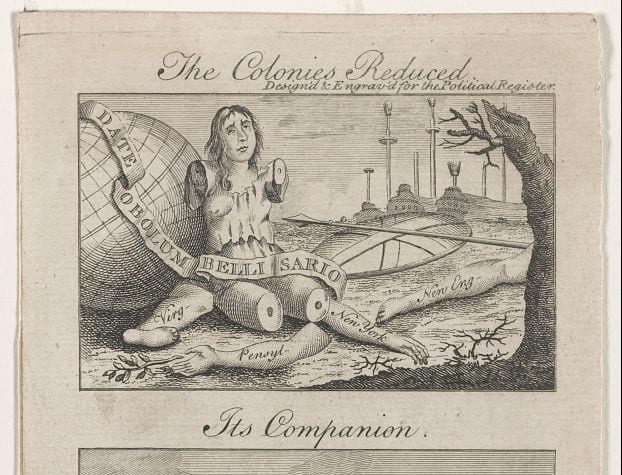

When they settled in North America, the colonists brought their religious beliefs with them. In most instances, this was accomplished not only as a matter of social or cultural transmission, but by acts of legislative authority that provided public funding for certain religious denominations and not for others. Only Pennsylvania, Delaware, Rhode Island and (possibly) New Jersey failed to establish a particular denomination at some point during the colonial period: in the other colonies, religious establishments were the norm, and generally seen as for the institutional benefit of both church and state, as well as in accordance with the public good. Some colonies (such as Maryland and New York) combined religious establishments with limited toleration for religious dissenters. Yet even in Pennsylvania, although the law was ostensibly “tolerant” of religious variety and protective of freedom of conscience in principle, there remained an underlying presumption that individual religious faith in a broadly Protestant sense (sometimes extended to include Catholics and, more rarely, Jews) was a necessary component of civil order.

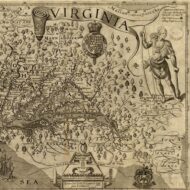

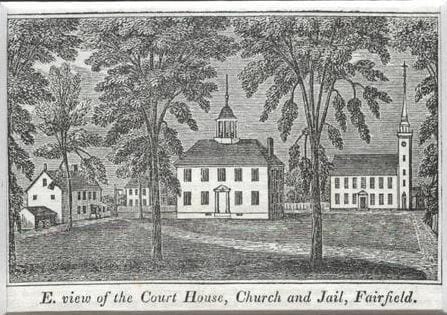

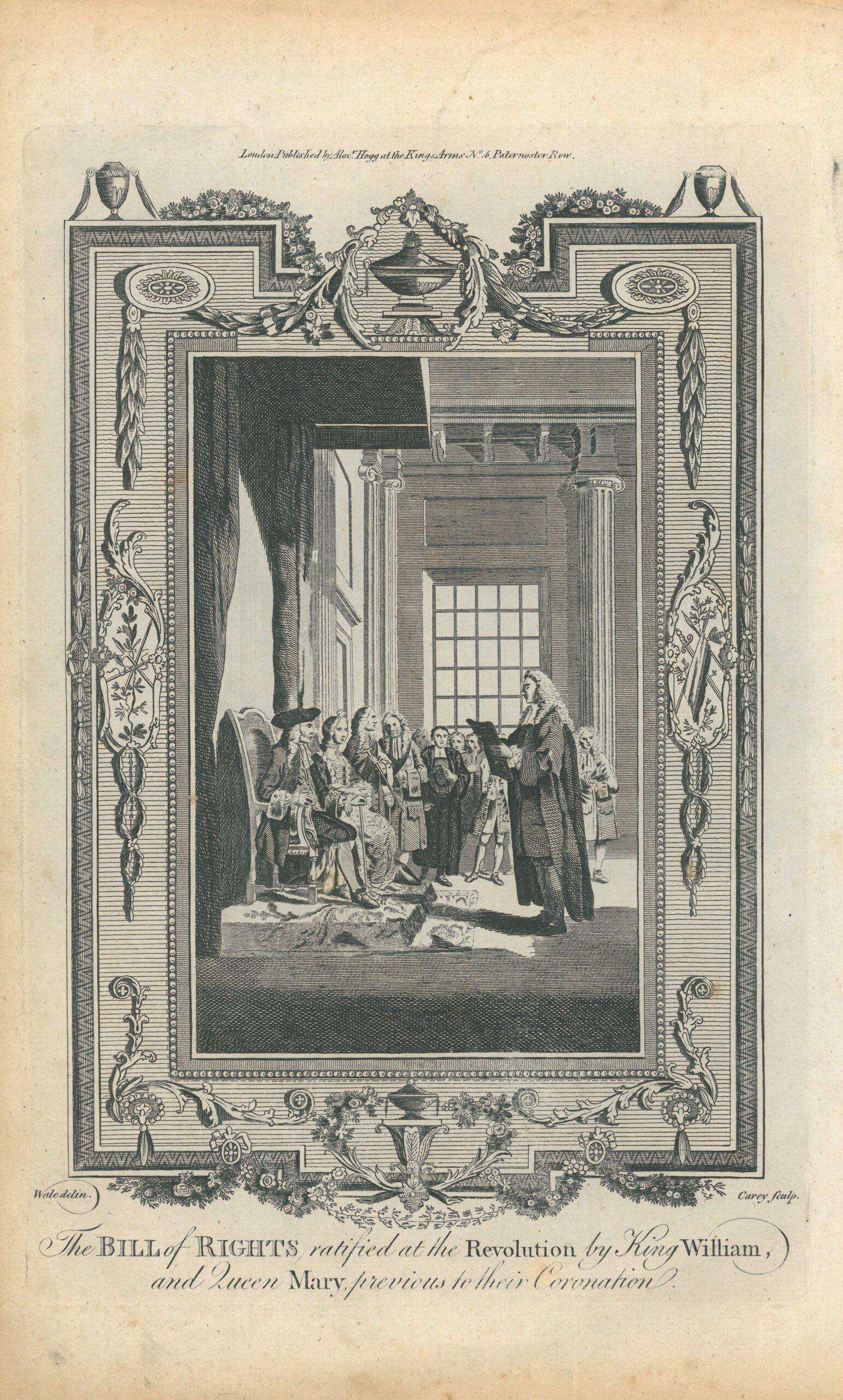

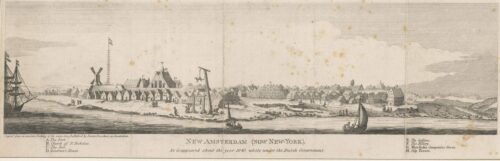

The difficulty of maintaining this latter assumption while at the same time holding to an expansive understanding of freedom of conscience became even more apparent when, following the Glorious Revolution, William and Mary signed the Toleration Act of 1689 granting freedom of worship to all Protestants regardless of sect throughout the British Empire. England and her Atlantic colonies soon became a haven for religious refugees from less-tolerant European regimes. After their arrival in places like New York, which already had large and religiously diverse non-English populations, the colonies began to seem “very much divided,” at least in the eyes of those used to greater religious conformity. Indeed, the vibrant but worrisome diversity of religion in the colonies was the impetus behind efforts to establish the Church of England more strongly as a means of asserting royal authority and creating greater political as well as cultural unity.

As scholar and statesman Elisha Williams’ tract, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants, makes clear, however, for many colonists, religious freedom was seen as a natural and inalienable right, one that they would increasingly associate with other political rights worth fighting for – with words when possible, and weapons when necessary – as the century wore on.

Elisha Williams, The Essential Rights and Liberties of Protestants (1744). Williams (1694–1755) was a Congregational minister active in colonial politics.

. . . That the sacred scriptures are the alone rule of faith and practice to a Christian, all Protestants are agreed in; and must therefore inviolably maintain, that every Christian has a right of judging for himself what he is to believe and practice in religion according to that rule: Which I think on a full examination you will find perfectly inconsistent with any power in the civil magistrate to make any penal laws in matters of religion. Tho’ Protestants are agreed in the profession of that principle, yet too many in practice have departed from it. The evils that have been introduced thereby into the Christian church are more than can be reckoned up. Because of the great importance of it to the Christian and to his standing fast in that liberty wherewith Christ has made him free, you will not fault me if I am the longer upon it. The more firmly this is established in our minds; the more firm shall we be against all attempts upon our Christian liberty, and better practice that Christian charity towards such as are of different sentiments from us in religion that is so much recommended and inculcated in those sacred oracles, and which a just understanding of our Christian rights has a natural tendency to influence us to. . . .

The members of a civil state or society do retain their natural liberty in all such cases as have no relation to the ends of such a society. . . . Should a government therefore restrain the free use of the scriptures, prohibit men the reading of them, and make it penal to examine and search them; it would be a manifest usurpation upon the common rights of mankind, as much a violation of natural liberty as the attack of a highwayman upon the road can be upon our civil rights. And indeed with respect to the sacred writings, men might not only read them if the government did prohibit the same, but they would be bound by a higher authority to read them, notwithstanding any humane prohibition. The pretense of any authority to restrain men from reading the same, is wicked as well as vain. . . .

II. The members of a civil state do retain their natural liberty or right of judging for themselves in matters of religion. Every man has an equal right to follow the dictates of his own conscience in the affairs of religion. Everyone is under an indispensable obligation to search the scripture for himself (which contains the whole of it) and to make the best use of it he can for his own information in the will of God, the nature and duties of Christianity. And as every Christian is so bound; so he has an unalienable right to judge of the sense and meaning of it, and to follow his judgment wherever it leads him; even an equal right with any rulers be they civil or ecclesiastical. This I say, I take to be an original right of the human nature, and so far from being given up by the individuals of a community that it cannot be given up by them if they should be so weak as to offer it. Man by his constitution as he is a reasonable being capable of the knowledge of his Maker; is a moral & accountable being: and therefore as everyone is accountable for himself, he must reason, judge and determine for himself. That faith and practice which depends on the judgment and choice of any other person, and not on the person’s own understanding judgment and choice, may pass for religion in the synagogue of Satan, whose tenet is that ignorance is the mother of devotion; but with no understanding Protestant will it pass for any religion at all. No action is a religious action without understanding and choice in the agent. Whence it follows, the rights of conscience are sacred and equal in all, and strictly speaking unalienable. This right of judging every one for himself in matters of religion results from the nature of man, and is so inseparably connected therewith, that a man can no more part with it than he can with his power of thinking: and it is equally reasonable for him to attempt to strip himself of the power of reasoning, as to attempt the vesting of another with this right. And whoever invades this right of another, be he pope or Cæsar, may with equal reason assume the other’s power of thinking, and so level him with the brutal creation. A man may alienate some branches of his property and give up his right in them to others; but he cannot transfer the rights of conscience, unless he could destroy his rational and moral powers, or substitute some other to be judged for him at the tribunal of God.

But what may further clear this point and at the same time shew the extent of this right of private judgment in matters of religion, is this truth, that the sacred scriptures are the alone rule of faith and practice to every individual Christian. Were it needful I might easily show the sacred scriptures have all the characters necessary to constitute a just and proper rule of faith and practice, and that they alone have them. It is sufficient for all such as acknowledge the divine authority of the scriptures, briefly to observe, that God the author has therein declared he has given and designed them to be our only rule of faith and practice. Thus says the apostle Paul, 2 Tim. 3. 15, 16; That they are given by Inspiration from God, and are profitable for Doctrine, for Reproof, for Correction, for Instruction in Righteousness; that the Man of God may be perfect, thoroughly furnished unto every good Work. . . . Now inasmuch as the scriptures are the only rule of faith and practice to a Christian; hence every one has an unalienable right to read, enquire into, and impartially judge of the sense and meaning of it for himself. For if he is to be governed and determined therein by the opinions and determinations of any others, the scriptures cease to be a rule to him, and those opinions or determinations of others are substituted in the room thereof. . . .