No related resources

Introduction

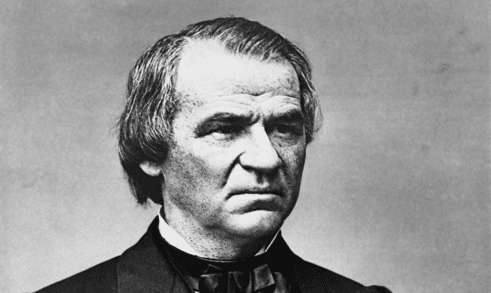

Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) came to office as president in 1869 determined to pursue a policy of peace with Native Americans. The Homestead Act (1862), which opened federal land in the West to settlement, and the construction of railroads (the first transcontinental line opened in 1869) increased the likelihood of conflict between the Indians and settlers, buffalo hunters, and miners. Following the Sand Creek massacre (1864), in which a militia cavalry killed several hundred Native Americans, including women and children, and the Fetterman Fight, or Massacre (1866), in which Indians killed all eighty-one members of a cavalry contingent, the U.S. government launched investigations that led to the appointment of a Peace Commission to negotiate treaties with various Indian tribes.

In his First Annual Message, Grant followed up on the work of the Peace Commission, arguing that a less confrontational approach to the Native Americans was necessary, not only to protect the Indians but also to prevent the brutalization of American society. “A system which looks to the extinction of a race is too horrible for a nation to adopt without entailing upon itself the wrath of all Christendom and engendering in the citizen a disregard for human life and the rights of others, dangerous to society.” To protect both Indians and American citizens, Grant proposed placing Indians on reservations, where the U.S. government would protect them and they could become civilized. Encouraging Indians to own lands individually, as Grant noted in his First Annual Message, was considered to be part of the process of civilizing them. An important part of Grant’s new policy was to use religious groups as agents of the U.S. government to deal with the tribes.

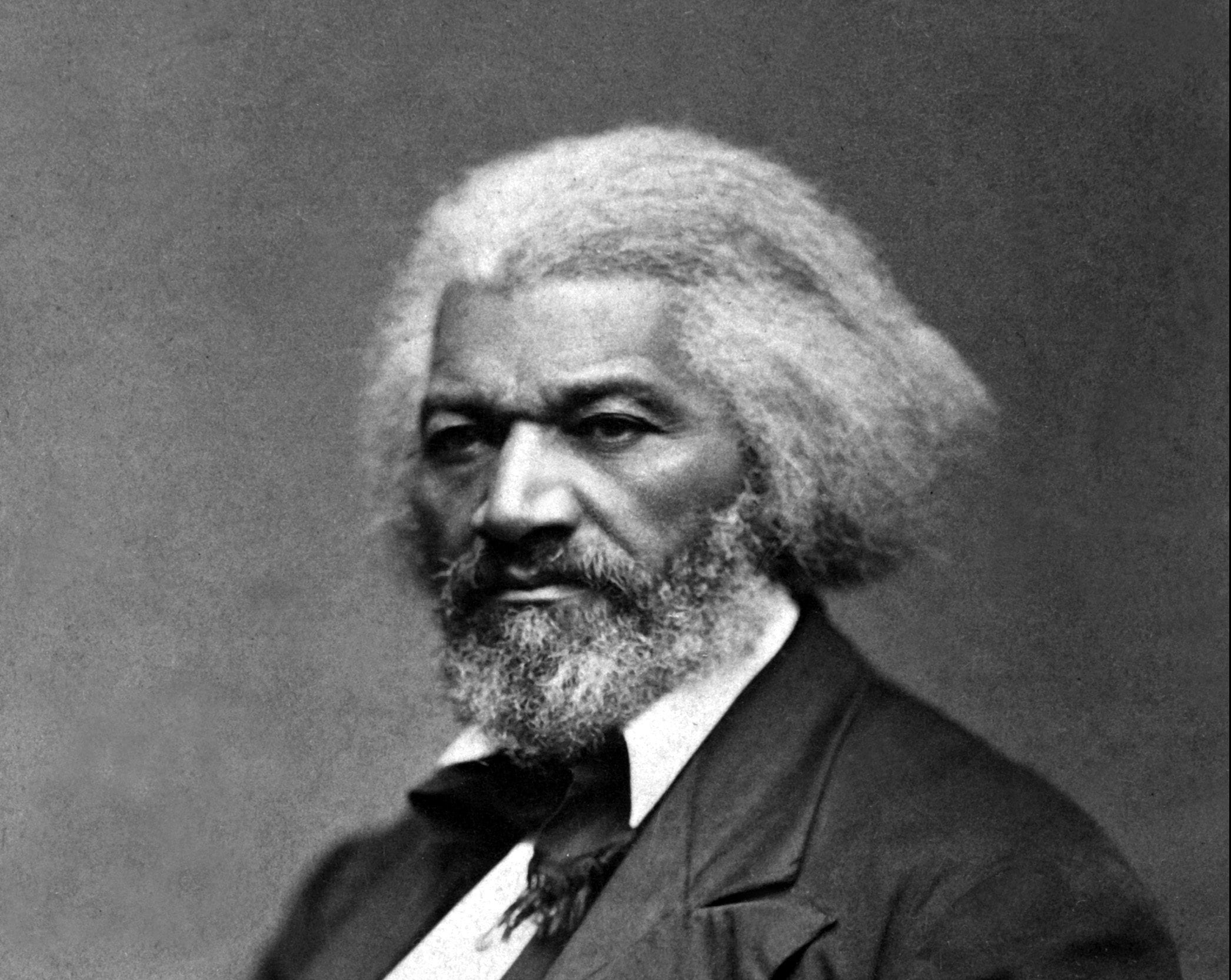

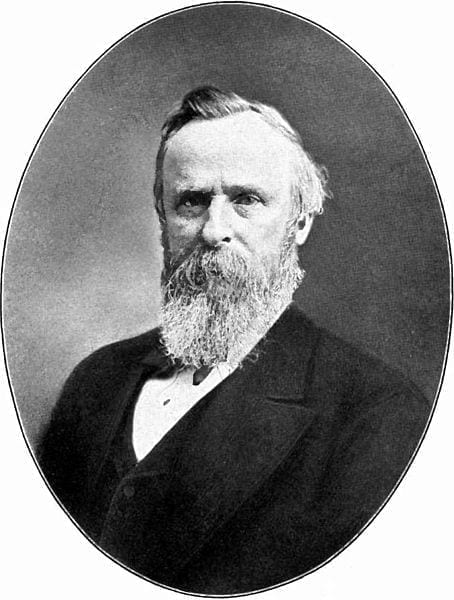

To carry out his new policy, Grant appointed a Board of Indian Commissioners to examine the system of government agents or traders who supplied the Indians with food, tools, and other necessities. This system was notoriously corrupt, as the commissioners documented in their reports. Grant also appointed Ely S. Parker (1828–1895) as the commissioner of Indian Affairs. Parker was a Seneca Indian who studied to be a lawyer but was not allowed to become one because Native Americans at that time were not citizens (in 1924 by act of Congress they became so). He then became an engineer, met Ulysses S. Grant while working in Galena, Illinois, joined the Union Army during the Civil War, and became Grant’s secretary. He was present at Appomattox when Lee surrendered. When Lee saw Parker, he reportedly remarked, “I am glad to see one real American here,” to which Parker replied, “We are all Americans.” Parker was the first Native American to hold the post of commissioner of Indian Affairs. After being accused of misusing funds, he was cleared by a congressional investigation but resigned in 1871.

In his report for 1869, Parker comments on efforts to carry out Grant’s peace policy. See here for more on Parker.

Source: Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, made to the Secretary of the Interior for the year 1869 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870), 3–6. Available at https://archive.org/details/1870annualreport00unitrich.

Sir: As required by law, I have the honor to submit this, my first annual report of our Indian Affairs and relations during the past year, with accompanying documents.

Among the reports of the superintendents and agents herewith,[1] there will be found information, with views and suggestions of much practical value, which should command the earnest attention of our legislators, and all others who are concerned for the future welfare and destiny of the remaining original inhabitants of our country. The question is still one of the deepest interest, “What shall be done for the amelioration and civilization of the race?” For a long period in the past, great and commendable efforts were made by the government to accomplish these desirable ends, but the success was never commensurate with the means employed. Of late years a change of policy was seen to be required as the cause of failure, the difficulties to be encountered, and the best means of overcoming them, became better understood. The measures to which we are indebted for an improved condition of affairs are the concentration of the Indians upon suitable reservations, and the supplying them with means for engaging in agricultural and mechanical pursuits for their education and moral training. As a result, the clouds of ignorance and superstition in which many of these people were so long enveloped, have disappeared, and the light of Christian civilization seems to have dawned upon their moral darkness, and opened upon a brighter future. Much, however, remains to be done for the multitude yet in their savage state, and I can but earnestly invite the serious consideration of those whose duty it is to legislate in their behalf, to the justice and importance of promptly fulfilling all treaty obligations and the wisdom of placing at the disposal of the department adequate funds for the purpose, and investing it with powers to adopt the requisite measures for the settlement of all tribes, when practicable, upon tracts of land to be set apart for their use and economy. I recommend that in addition to the reservations already established, there be others provided for the wild and roving tribes of New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada; also for the more peaceable bands in the southern part of California. These tribes, excepting the Navahos in the territory of New Mexico, who under the Treaty of 1868, have a home in the western part of the territory to which they have been removed, have no treaty relations with the government, and if placed upon reservations, it will be necessary that Congress, by appropriating legislation, provide for their wants, until they become capable of taking care of themselves. In the other territories, as also in Oregon and the northern part of California, the existing reservations are sufficient to accommodate all the Indians within their bounds; indeed, the number might with advantage be reduced; but in Montana there is urgent need for the setting apart, permanently suitable tracts for the Blackfeet and other tribes, who claim large portions of that territory and are parties to treaties entered into with them last year by Commissioner W. J. Cullen,[2] which were submitted to the United States Senate, but have not been finally acted upon by that body. Should the treaties be ratified, the required reservations will be secured, greatly to the benefit of both Indians and citizens.

Before entering upon a résumé of affairs of the respective superintendencies of agencies for the past year, I will here briefly notice several matters of interest which in their bearing upon the management of our Indian relations, are likely to work out judging from what has been the effect so far, the most beneficial results.

Under an act of Congress approved April 10, 1868, two million dollars[3] were appointed to enable the president to maintain peace among and with various tribes, bands, and parties of Indians; to promote their civilization; bring them, when practicable, upon reservations, and to relieve their necessities, and encourage their efforts at self-support. The Executive[4] is also authorized to organize a Board of Commissioners, to consist of not more than ten persons, selected from among men eminent for their intelligence and philanthropy, to serve without pecuniary compensation, and who, under his direction, shall exercise joint control with the secretary of the interior over the disbursement of this large fund. . . .

In regard to the fund of two million dollars referred to, it may be remarked that it has enabled the department to a great extent to carry out the purpose for which it was appropriated. There can be no question but that mischief has been prevented and suffering either relieved or warded off from numbers who otherwise by force or circumstances would have been led into difficulties and extreme want. By the timely supplies of subsistence and clothing furnished, and the adoption of measures for their benefit, the tribes from whom the greatest trouble was apprehended have been kept comparatively quiet, and some advance it is to be hoped, made in the direction of their permanent settlement in the localities assigned to them, and their entering upon a new course of life. The subsistence they receive is furnished through the agency of the commissary department of the Army, with, it is believed, greater economy and more satisfaction than could have resulted had the mode heretofore been followed.[5] In this connection I desire to call attention to the fact that the number of wild Indians and other, also not provided for by treaty stipulations, whose precarious condition requires that something should be done for relief and who are thrown under the immediate charge of the department, is increasing. It is therefore, a matter of serious consideration and urgent necessity that means be offered to properly care for them. For this purpose, in my judgment there should be annually appropriated by Congress, a large contingent fund similar to that in question, and subject to the same control. I accordingly recommend that the subject be brought to the attention of Congress.

With a view of more efficiency in the management of affairs of the respective superintendencies and agencies, the Executive has inaugurated a change of policy whereby a different class of men from those heretofore selected, have been appointed to duty as superintendents and agents. There are doubtless just grounds for it, as great and frequent complaints have been made for years past, of either the dishonesty or inefficiency of many of these officers. Members of the Society of Friends,[6] recommended by the society, now hold these positions in the Northern Superintendency, embracing all Indians in Nebraska; and in the Central [Superintendency], embracing tribes residing in Kansas, together with the Kiowas, Comanches, and other tribes in the Indian country. Other superintendencies and agencies, excepting that of Oregon and two agencies there, are filled by Army officers detailed for such duty. The experiment has not been sufficiently tested to enable me to say definitively that it is a success, for but a short time has elapsed since these Friends and officers entered upon duty; but so far as I can learn, the plan works advantageously, and will probably prove a positive benefit to the service, and the indications are that the interests of the government and the Indians will be subserved by an honest and faithful discharge of duty, fully answering the expectations entertained by those who regard the measure as wise and proper.

I am pleased to have it to remark that there is now a perfect understanding between the officers of this department and those of the military, with respect to their relative duties and responsibilities in reference to the Indian affairs. In this matter with the approbation of the president and yourself a circular letter was addressed to this office in June last to all superintendents and agents, defining the policy of the government in its treatments of the Indians, as comprehended in there general terms, viz.: that they should be secured their legal rights; located, when practicable, upon reservations; assisted in agricultural pursuits and the arts of civilized life and that Indians who should fail or refuse to come in and locate in permanent abodes provided for them, must be subject wholly to the control and supervision of military authorities, to be treated as friendly or hostile as circumstances might justify. The War Department concurring, issued orders upon the subject for the information and guidance of the proper military officers, and the result has been harmony of action between two departments, no conflict of opinion having arisen as to the duty, power, and responsibility of either.[7]

Arrangements now, as heretofore, will doubtless be required with tribes desiring to be settled upon reservations for the relinquishment of their rights to the lands claimed by them, and for assistance in sustaining themselves in a new position, but I am of the opinion that they should not be of a treaty nature.[8] It has become a matter of serious import whether the treaty system in use ought longer to be continued. In my judgment it should not. A treaty involves the idea of a compact between two or more sovereign powers, each possessing of sufficient authority and force to compel a compliance with the obligations incurred. The Indian tribes of the United States are not sovereign nations, capable of making treaties, as none of them have an organized government of such inherent strength as would secure a faithful obedience of its people in the observance of compacts of this character. They are held to be the wards of the government, and the only title the law concedes to them to the lands they occupy or claim is a mere possessory one. But because treaties have been made with them generally for the extinguishment of their supposed absolute title to land inhabited by them, or over which they roam, they have become falsely impressed with the notion of national independence. It is time that this idea should be dispelled, and that the government cease the cruel farce of thus dealing with its helpless and ignorant wards. Many good men, looking at this matter only from a Christian point of view, will perhaps say that the poor Indian has been greatly wronged and ill-treated; that this whole county was once his of which he has been despoiled, and that he has been driven from place to place until he has hardly left to him a spot where to lay his head. This indeed may be philanthropic, and humane, but the stern letter of the law admits of no conclusion, and great injury has been done by the government deluding these people into the belief of their being independent sovereignties, while they were at the same time recognized only as its dependents and wards. As civilization advances and their possessions of land are required for settlement, such legislation should be granted to them as a wise, liberal and just government ought to extend to its subjects holding their dependent relation. In regard to the treaties now in force, justice and humanity require that they be promptly and faithfully executed, so that the Indians may not have the cause of complaint, or reason to violate their obligation by acts of violence and robbery. . . .

- 1. Superintendents and agents were individuals appointed by the government to deal with the Indians. Superintendents had responsibility for several tribes; agents dealt with individual tribes.

- 2. Cullen was not a member of the new Board of Commissioners but a government employee who negotiated treaties with various Indian tribes.

- 3. Equivalent to $33 million in 2017. Two million dollars was 0.5 percent of the federal budget in 1868. An equivalent percentage of the budget in 2017 would be roughly $18 billion

- 4. The president of the United States.

- 5. Civilian agents had previously carried out this role.

- 6. The Quakers were known for their philanthropic work and were among the first opponents of slavery in the United States. Other Protestant denominations, and eventually Catholics and Jews, also worked with the Indians.

- 7. The War Department had long had the job of dealing with and policing the Indians. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was created in the War Department in 1824. The post of commissioner of Indian Affairs was created in 1832. The BIA became part of the Department of the Interior when it was created in 1849. For years, the War Department, still policing the Indians, and the Interior Department and its Bureau of Indian Affairs, sparred over Indian policy. For example, the BIA supplied weapons to the Indians so they could continue to hunt, but the War Department complained that the Indians used the weapons to raid civilians and fight the U.S. Army’s cavalry

- 8. See Worcester v. Georgia

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.