No related resources

Introduction

The railroads that spread westward beyond the Mississippi after the Civil War were the leading edge of the industrial revolution that transformed the American economy and America itself. Although the number of farms and the number of Americans involved in farming continued to grow for a few decades after the Civil War as settlers moved west, the percentage of Americans involved in agriculture started a long-term decline in these years. In 1860 about 64 percent of Americans were farmers; in 2019 just more than 1 percent are. More important, railroads drew farmers in the West deeper into the national market economy at the same time corporations became more powerful in that economy. The railroads were the principal way in which farmers in the West experienced the new power of corporations.

Farmers throughout the country responded to these economic changes by joining together to counter the economic forces affecting their lives. In doing so, they voiced attitudes and ideas that Thomas Jefferson had first articulated almost one hundred years before. The western farming settlements fulfilled Jefferson’s vision of America as a nation of farmers, as the farmers explained themselves in Jeffersonian language, but this vision was challenged by the kind of corporate commercial power that Jefferson’s great antagonist, Alexander Hamilton, had hoped would raise America to national greatness.

The first document below, a report on a state farmers’ convention, shows the response of farmers in one western state to the economic challenges they encountered. It also shows their belief that they needed national organizations as powerful as the new corporations if they were to preserve the way of life they hoped to live on the vast western lands. The second document states the purposes and the proposed economic and political reforms of one of the national farmer organizations—the Grange—that developed at this time. Although the Grange and other farmer organizations did not enjoy much success, their ideas did become part of the subsequent Populist movement, and eventually part of the Progressive movement, which did have a profound effect on American politics and life.

Source: The document on the Kansas Cooperative Association comes from Jonathan Periam, The Groundswell: A History of the Origin, Aims, and Progress of the Farmers’ Movement (Cincinnati: E. Hannaford and Co.; San Francisco: F. Dewing and Co.; Chicago: Hannaford and Thompson, 1874), 271–278, available at https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=7IFIAAAAYAAJ&pg=GBS.PR3. The documents on the national Grange come from A Documentary History of American Industrial Society, vol. 10, ed. J. R. Commons et al. (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co., 1911), 86–87, 100–105, available at https://archive.org/details/documentaryhisto10commuoft/page/n9/mode/2up.

The Kansas Farmers’ Cooperative Association, the State Convention at Topeka

On the 26th of March, 1873, a mass convention of the farmers of Kansas was held at Topeka, at which was formed the now powerful organization known as the “Farmers’ Cooperative Association of the State of Kansas.” The meeting originated with the Manhattan Farmers’ Club, which passed resolutions requesting the secretary of the State Board of Agriculture, Mr. Alfred Gray, to call a state convention, to be composed of delegates from farmers’ clubs. This was done, and, subsequently, the call was enlarged so as to include farmers’ unions, granges, and other similar organizations.[1]

While the formal initiatory business of the convention was being transacted, Mr. Henry Bronson, Dr. Lawrence, and Mr. Van Winkle delivered addresses on the incidents of taxation, and farmers’ grievances generally. The speaker first mentioned declared that it was because of a false financial system, and a false political system no longer bearable, saddled on the people, that the farmers have come here to see if they cannot be righted. It is useless to say they can do nothing; for they have the votes and the power, though want of organization has kept them from accomplishing these reforms. Just so soon as organization is effected they will be as strong as they are now weak. It matters not whether this be done by farmers’ unions or by the Patrons of Husbandry, and he would never quarrel with the means that accomplished these ends, and desired all to work with the means and tools that suited best; but there should be no antagonism. They had strong powers to combat, and when they met them in fight should be confident that they were strong enough to cope with the enemy. He counseled them to avoid divisions, and believed that there was a working force in the land that would culminate in a strength sufficient to make their efforts a success. . . .

After adopting a resolution limiting speeches to ten minutes, a committee was appointed to draft a constitution for a permanent organization. In the course of the discussion which preceded this action, Governor Robinson[2] said that the only benefit which the farmer could hope for was by well-considered organization. The old question of demand and supply was obsolete and played out; none of the great interests were using it. It was, instead, the new word of combination which determines the price at which iron and other commodities are sold from New York to San Francisco. All classes, whether they be mechanics, engineers, shoemakers, or bootblacks, combine and fix the price for their different products or labor. We have parallel lines of railroad, but they combine and do not compete. If the poor farmers were to combine and withhold their hands, the people would perish. There was but one course for the farmer to pursue, and he would not give one fig for anything they would accomplish unless they adopted it. He advocated county and state organizations, auxiliary to a national one, all to be in correspondence with headquarters; and that the National Directory[3] should set the price for farm products in our cities; who should find out all the statistics of interest to the farmer, average of grain and cost, and have an intelligent information of the prices determined in all our great cities. The state organizations should, within their limits, gather up such statistics and fix prices, and county societies should do the same. The farmer would then handle the same weapons, and be on the same footing with dealers in iron, wool, and cotton. He urged organization, and when organized, to correspond with headquarters, and agree to abide in good faith with the Board of Directory as to the movement of grain and prices. We can then obtain laws, regulate railroads and the price of every commodity to be bought by the farmer. They will give it up when this state of affairs occurs. While he did not advise any political action, his advice was to vote for the known friends of the former, wherever they might be found, and they would soon find out that they had plenty of friends. He hoped that some steps would be taken by the convention in the right direction.

Resolutions and Debate Thereon

Various resolutions were submitted and referred to a committee, which, subsequently, reported the following:

Resolved, That organization is the great want of the producing classes at the present time, and we recommend every farmer in the state to become a member of some farmers’ club, grange of the Patrons of Husbandry, or other local organization.

Resolved, That the taxes assessed and charged upon the people, both by national, state, and local governments, are oppressive and unjust, and vast sums of money are collected far beyond the needs of an economical administration of government.

Resolved, That we respectfully request our senators and representatives in Congress to vote for, and secure, an amendment to the tariff laws of the United States, so that salt and lumber shall be placed on the free list, and that there shall be made a material reduction of the duty on iron, and that such articles as do not pay the cost of collection be also placed on the free list.

Resolved, That we demand that the legislature of our state shall pass a law limiting railroad freights and fares to a just and fair sum, and that unjust discriminations against local freights be prohibited.

Resolved, That the act passed by the last legislature, exempting bonds, notes, mortgages, and judgments from taxation, is unjust, oppressive, and a palpable violation of our state constitution, and we call upon all assessors and the county boards to see that said securities are taxed at their fair value.

A debate ensued on the first resolution. Mr. Lines objected to the granges on the ground of their secrecy feature,[4] and moved that the words “grange of Patrons of Husbandry” be stricken out. After a discussion, in which it appeared that Mr. Lines was almost alone in his views, the amendment was withdrawn, and the original resolution was afterward carried. The second resolution was passed unanimously.

On the tariff resolution a lively discussion took place, in which statistics were given by Major Miller, of the State Agricultural College, showing that the tariff on iron did not account for the difference in the price of that article in the United States and England. Mr. Christopher gave some details about the Syracuse salt ring,[5] and their manner of crowding out competition. Mr. Van Winkle moved to amend the resolution by leaving out salt and iron. The amendment was lost, and the resolution carried.

When the resolution on railroad freights came on for consideration, Mr. Lines moved, as a substitute: That we earnestly request the legislature of our state, at its next session, to enact a law regulating freights and fares upon our railroads upon a basis of justice; and that we further request our members in Congress to urge the favorable action of that body, where the same power exists beyond all doubt, to the same end, and, if need be, to construct national highways at the expense of the government.

After a discussion, this was adopted instead of the original resolution. The other resolutions, after discussion, were adopted. . . .

Mr. Alfred Gray was elected corresponding agent to communicate with the principal manufacturers of agricultural implements, and dealers in the same, with a view to obtaining low rates of purchase, and also to make application for reduced rates of transportation on all the different railroads, and forward a statement of advantages obtained monthly to each of the different organizations of farmers within the state. . . .

Resolved, That it is the sense of this convention that the farmers of Kansas, while they are ready to denounce in unmeasured terms every monopoly that strikes at their interests in the shape of robbery and oppression, are equally ready to admit any and all wrongs and errors of their own that have brought them into the dilemma which all complain of to-day. . . .

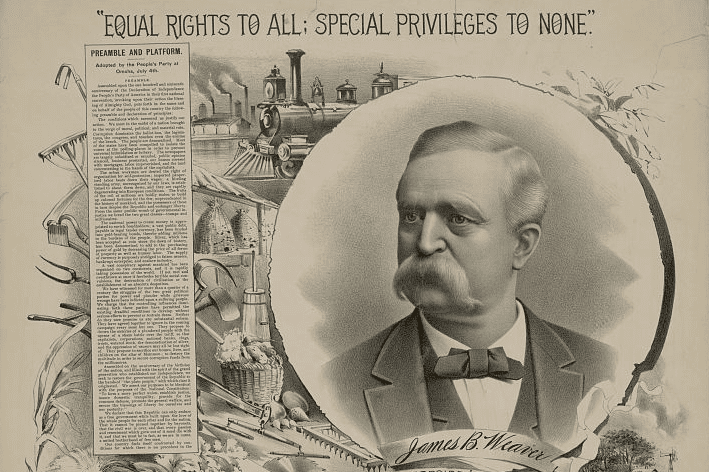

Preamble to the Constitution of the National Grange, January 8, 1873

Human happiness is the acme of earthly ambition. Individual happiness depends upon general prosperity.

The prosperity of a nation is in proportion to the value of its production.

The soil is the source from whence we derive all that constitutes wealth; without it we would have no agriculture, no manufactures, no commerce. Of all the material gifts of the Creator, the various productions of the vegetable world are of the first importance. The art of agriculture is the parent and precursor of all arts, and its products the foundation of all wealth.

The productions of the earth are subject to the influence of natural laws, invariable and indisputable; the amount produced will consequently be in proportion to the intelligence of the producer, and success will depend upon his knowledge of the action of these laws, and the proper application of their principles.

Hence, knowledge is the foundation of happiness.

The ultimate object of this organization is for mutual instruction and protection, to lighten labor by diffusing a knowledge of its aims and purposes, to expand the mind by tracing the beautiful laws the Great Creator has established in the Universe, and to enlarge our views of creative wisdom and power.

To those who read aright, history proves that in all ages society is fragmentary, and successful results of general welfare can be secured only by general effort. Unity of action cannot be acquired without discipline, and discipline cannot be enforced without significant organization; hence we have a ceremony of initiation which binds us in mutual fraternity as with a band of iron; but, although its influence is so powerful, its application is as gentle as that of the silken thread that binds a wreath of flowers.

Declaration of Purposes of the National Grange, February 11, 1874

General Objects

- United by the strong and faithful tie of agriculture, we mutually resolve to labor for the good of our order, our country, and mankind.

- We heartily endorse the motto: “In essentials, unity; in nonessentials, liberty; in all things, charity.”[6]

Specific Objects

- We shall endeavor to advance our cause by laboring to accomplish the following objects:

To develop a better and higher manhood and womanhood among ourselves; to enhance the comforts and attractions of our homes, and strengthen our attachments to our pursuits; to foster mutual understanding and cooperation; to maintain inviolate our laws, and to emulate each other in labor, to hasten the good time coming; to reduce our expenses, both individual and corporate; to buy less and produce more, in order to make our farms self-sustaining; to diversify our crops and crop no more than we can cultivate; to condense the weight of our exports, selling less in the bushel and more on hoof and in fleece, less in lint and more in warp and woof; to systematize our work, and calculate intelligently on probabilities; to discountenance the credit system, the mortgage system, the fashion system, and every other system tending to prodigality and bankruptcy.

We propose meeting together, talking together, working together, buying together, selling together, and, in general, acting together for our mutual protection and advancement, as occasion may require. We shall avoid litigation as much as possible by arbitration in the Grange. We shall constantly strive to secure entire harmony, good will, vital brotherhood among ourselves, and to make our order perpetual. We shall earnestly endeavor to suppress personal, local, sectional, and national prejudices, all unhealthy rivalry, all selfish ambition. Faithful adherence to these principles will insure our mental, moral, social, and material advancement.

Business Relations

- For our business interests we desire to bring producers and consumers, farmers and manufacturers, into the most direct and friendly relations possible. Hence, we must dispense with a surplus of middlemen, not that we are unfriendly to them, but we do not need them. Their surplus and their exactions diminish our profits. . . .

. . . We shall . . . advocate for every state the increase in every practicable way, of all facilities for transporting cheaply to the seaboard, or between home producers and consumers, all the productions of our country. We adopt it as our fixed purpose to “open out the channels in Nature’s great arteries, that the lifeblood of commerce may flow freely.”[7]

We are not enemies of railroads, navigable and irrigating canals, nor of any corporation that will advance our industrial interests, nor of any laboring classes.

In our noble order there is no communism, no agrarianism.[8]

We are opposed to such spirit and management of any corporation or enterprise as tends to oppress the people and rob them of their just profits. We are not enemies to capital, but we oppose the tyranny of monopolies. We long to see the antagonism between capital and labor removed by common consent, and by an enlightened statesmanship worthy of the nineteenth century. We are opposed to excessive salaries, high rates of interest, and exorbitant profits in trade. They greatly increase our burdens and do not bear a proper proportion to the profits of producers. We desire only self-protection and the protection of every true interest of our land, by legitimate transactions, legitimate trade, and legitimate profits. . . .

The Grange Not Partisan

- We emphatically and sincerely assert the oft-repeated truth taught in our organic law, that the Grange—national, state, or subordinate—is not a political or party organization. No grange, if true to its obligation, can discuss partisan or sectarian questions, nor call political conventions, nor nominate candidates, nor even discuss their merits in its meetings.

Yet the principles we teach underlie all true politics, all true statesmanship, and, if properly carried out, will tend to purify the whole political atmosphere of our country. For we seek the greatest good to the greatest number. . . .

We desire a proper equality, equity, and fairness; protection for the weak; restraint upon the strong; in short, justly distributed burdens and justly distributed power. These are American ideas, the very essence of American independence, and to advocate the contrary is unworthy of the sons and daughters of an American Republic.

We cherish the belief that sectionalism is, and of right should be, dead and buried with the past. . . .

- . . . [W]e appeal to all good citizens for their cordial cooperation and assistance in our efforts toward reform, that we may eventually remove from our midst the last vestige of tyranny and corruption. We hail the general desire for fraternal harmony, equitable compromises, and earnest cooperation as an omen of our future success.

- It shall be an abiding principle with us to relieve any of our oppressed and suffering brotherhood by any means at our command.

Last, but not least, we proclaim it among our purposes to inculcate a proper appreciation of the abilities and sphere of woman, as is indicated by admitting her to membership and position in our order.

Imploring the continued assistance of our Divine Master to guide us in our work, we here pledge ourselves to faithful and harmonious labor for all future time, to return by our united efforts to the wisdom, justice, fraternity, and political purity of our forefathers.

- 1. Farmers’ unions and the Grange (the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry) were organizations, like the Kansas Farmers’ Cooperative Association, that hoped to serve the interests of farmers through collective action. The first grange was organized in 1868 in New York. A national Grange organization emerged in the 1870s, as did the Farmers’ Alliance, another national farmers’ organization, also founded in New York. The word “grange” comes from a Latin word meaning grain house or farm.

- 2. Charles L. Robinson (1818–1894) was the first governor of Kansas (1861–1863). He was elected to the Kansas Senate in 1873.

- 3. The leadership of the national farmers’ organization that Robinson advocated.

- 4. The Grange modeled itself on the Freemasons. It held secret meetings and had degrees of membership.

- 5. A “ring” in this sense is an organization, with the implication that it is engaged in illegal behavior.

- 6. A phrase apparently originating during the religious wars of seventeenth-century Europe, and widely used since.

- 7. A quotation from the Grange’s principles of action

- 8. Communism is public ownership of property. Agrarianism is the view that farming is a life superior to or more economically important than others.

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.