Introduction

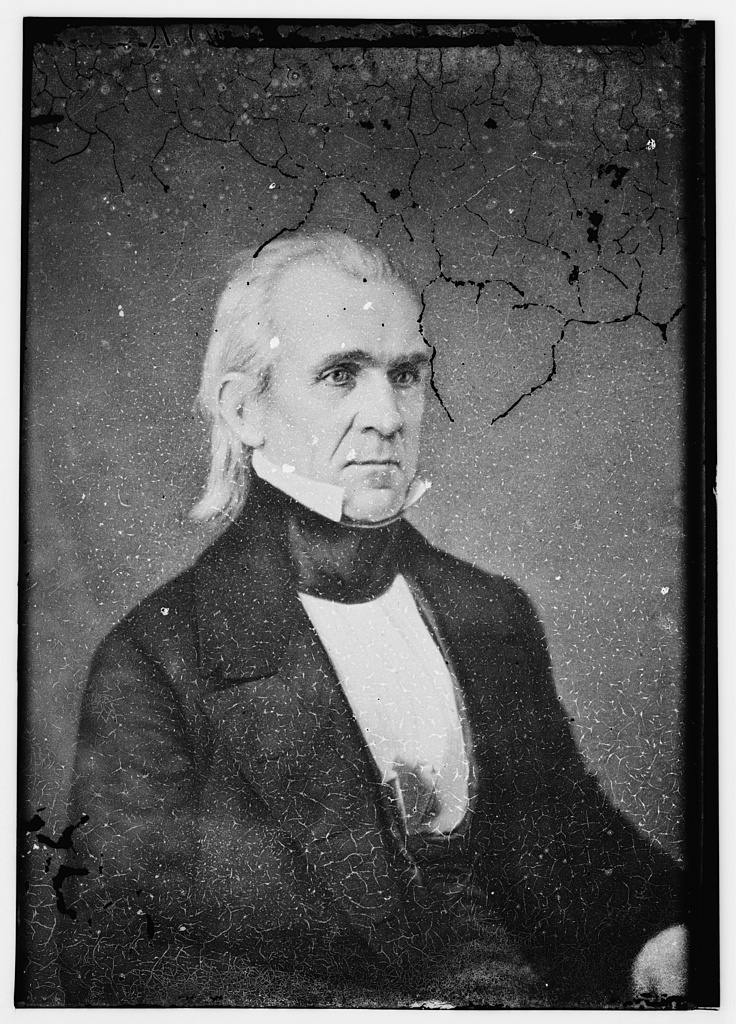

In his Raleigh Letter of April 1844, Henry Clay (1777–1852) had warned that the annexation of Texas by the United States would likely lead to war with Mexico, which had never fully recognized the independence of its former province. Following the U.S. annexation in 1845, the Mexican government severed diplomatic relations with the United States. President James Polk (1795–1849) subsequently sent an envoy, former Louisiana congressman John Slidell (1793–1871), to Mexico to try to resolve disputes over the Texas boundary and over damages that the Mexican government allegedly owed to U.S. citizens. Slidell was instructed to offer up to $30–40 million to pay off Mexico’s debt in order to acquire “Upper California and New Mexico.” Polk also ordered a contingent of American forces, led by Gen. Zachary Taylor (1784–1850), to occupy the territory between the Rio del Norte (Rio Grande) and the Nueces River, which both Mexico and Texas claimed.

When Mexico refused to sell, Polk began to prepare a declaration of war. Before its completion, however, he received reports from Taylor that Mexican forces had killed or wounded sixteen U.S. soldiers in the disputed territory. On May 11, 1846, Polk presented a special message to Congress announcing that “war exists” between the two countries because the Mexican government had “at last invaded our territory and shed the blood of our fellow-citizens on our own soil.” The message reviewed Polk’s diplomatic efforts (not reprinted below) but did not mention the offer to purchase New Mexico and California. It also described the movement of American troops and the subsequent, in Polk’s view, unwarranted aggression by Mexico. On May 12, 1846, Congress voted to approve a declaration of war against Mexico, or, literally, a declaration that a state of war now existed.

To ensure that Britain would not become involved in the war, Polk negotiated an agreement with London over the boundary of the Oregon Territory, which had been left unresolved by the Convention of 1818. Polk wanted a boundary that gave the United States access to a Pacific port and was prepared to compromise well short of the line of maximum American claims (54°40′, well into what is now British Columbia). This concession angered some anti–British northern Democrats, who adhered to the party’s popular slogan of “54-40 or fight” during the presidential campaign of 1844. Some Whig Party antislavery advocates, like John Quincy Adams, favored expansion but only into free territory. Ultimately, the Oregon Treaty of 1846 extended the boundary along the 49th parallel from the Rockies to the coast, leaving Vancouver Island in British hands and Juan de Fuca Strait between Vancouver Island and the Olympic Peninsula open to both countries, with the United States in possession of the lower Columbia River and the future port of Seattle, Washington.

James K. Polk, “Special Message to Congress on Mexican Relations,” May 11, 1846. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. https://goo.gl/o9uAFh.

The existing state of the relations between the United States and Mexico renders it proper that I should bring the subject to the consideration of Congress. In my message at the commencement of your present session, the state of these relations,[1] the causes which led to the suspension of diplomatic intercourse between the two countries in March, 1845, and the long-continued and unredressed wrongs and injuries committed by the Mexican Government on citizens of the United States in their persons and property were briefly set forth.

… Thus the government of Mexico, though solemnly pledged by official acts in October last to receive and accredit an American envoy, violated their plighted faith and refused the offer of a peaceful adjustment of our difficulties. Not only was the offer rejected, but the indignity of its rejection was enhanced by the manifest breach of faith in refusing to admit the envoy who came because they had bound themselves to receive him. Nor can it be said that the offer was fruitless from the want of opportunity of discussing it; our envoy was present on their own soil. Nor can it be ascribed to a want of sufficient powers; our envoy had full powers to adjust every question of difference. Nor was there room for complaint that our propositions for settlement were unreasonable; permission was not even given our envoy to make any proposition whatever. Nor can it be objected that we, on our part, would not listen to any reasonable terms of their suggestion; the Mexican government refused all negotiation, and have made no proposition of any kind.

In my message at the commencement of the present session I informed you that upon the earnest appeal both of the Congress and convention of Texas I had ordered an efficient military force to take a position “between the Nueces and the Del Norte.” This had become necessary to meet a threatened invasion of Texas by the Mexican forces, for which extensive military preparations had been made. The invasion was threatened solely because Texas had determined, in accordance with a solemn resolution of the Congress of the United States, to annex herself to our Union, and under these circumstances it was plainly our duty to extend our protection over her citizens and soil.

This force was concentrated at Corpus Christi, and remained there until after I had received such information from Mexico as rendered it probable, if not certain, that the Mexican Government would refuse to receive our envoy.

Meantime Texas, by the final action of our Congress, had become an integral part of our Union. The Congress of Texas, by its act of December 19, 1836, had declared the Rio del Norte to be the boundary of that Republic. . . . This river, which is the southwestern boundary of the State of Texas, is an exposed frontier. From this quarter invasion was threatened; upon it and in its immediate vicinity, in the judgment of high military experience, are the proper stations for the protecting forces of the Government. In addition to this important consideration, several others occurred to induce this movement. Among these are the facilities afforded by the ports at Brazos Santiago and the mouth of the Del Norte for the reception of supplies by sea, the stronger and more healthful military positions, the convenience for obtaining a ready and a more abundant supply of provisions, water, fuel, and forage, and the advantages which are afforded by the Del Norte in forwarding supplies to such posts as may be established in the interior and upon the Indian frontier.

The movement of the troops to the Del Norte was made by the commanding general under positive instructions to abstain from all aggressive acts toward Mexico or Mexican citizens and to regard the relations between that Republic and the United States as peaceful unless she should declare war or commit acts of hostility indicative of a state of war. He was specially directed to protect private property and respect personal rights. . . .

The Mexican forces at Matamoras assumed a belligerent attitude, and on the 12th of April General Ampudia,[2] then in command, notified General Taylor to break up his camp within twenty-four hours and to retire beyond the Nueces River, and in the event of his failure to comply with these demands announced that arms, and arms alone, must decide the question. But no open act of hostility was committed until the 24th of April. On that day General Arista,[3] who had succeeded to the command of the Mexican forces, communicated to General Taylor that “he considered hostilities commenced and should prosecute them.” A party of dragoons of sixty-three men and officers were on the same day dispatched from the American camp up the Rio del Norte, on its left bank, to ascertain whether the Mexican troops had crossed or were preparing to cross the river, “became engaged with a large body of these troops, and after a short affair, in which some sixteen were killed and wounded, appear to have been surrounded and compelled to surrender.”

The grievous wrongs perpetrated by Mexico upon our citizens throughout a long period of years remain unredressed, and solemn treaties pledging her public faith for this redress have been disregarded. A government either unable or unwilling to enforce the execution of such treaties fails to perform one of its plainest duties.

Our commerce with Mexico has been almost annihilated. It was formerly highly beneficial to both nations, but our merchants have been deterred from prosecuting it by the system of outrage and extortion which the Mexican authorities have pursued against them, whilst their appeals through their own Government for indemnity have been made in vain. Our forbearance has gone to such an extreme as to be mistaken in its character. Had we acted with vigor in repelling the insults and redressing the injuries inflicted by Mexico at the commencement, we should doubtless have escaped all the difficulties in which we are now involved.

Instead of this, however, we have been exerting our best efforts to propitiate her good will. Upon the pretext that Texas, a nation as independent as herself, thought proper to unite its destinies with our own she has affected to believe that we have severed her rightful territory, and in official proclamations and manifestoes has repeatedly threatened to make war upon us for the purpose of reconquering Texas. In the meantime, we have tried every effort at reconciliation. The cup of forbearance had been exhausted even before the recent information from the frontier of the Del Norte. But now, after reiterated menaces, Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon the American soil. She has proclaimed that hostilities have commenced, and that the two nations are now at war.

As war exists, and, notwithstanding all our efforts to avoid it, exists by the act of Mexico herself, we are called upon by every consideration of duty and patriotism to vindicate with decision the honor, the rights, and the interests of our country.

In further vindication of our rights and defense of our territory, I invoke the prompt action of Congress to recognize the existence of the war, and to place at the disposition of the Executive the means of prosecuting the war with vigor, and thus hastening the restoration of peace. To this end I recommend that authority should be given to call into the public service a large body of volunteers to serve for not less than six or twelve months unless sooner discharged. A volunteer force is beyond question more efficient than any other description of citizen soldiers, and it is not to be doubted that a number far beyond that required would readily rush to the field upon the call of their country. I further recommend that a liberal provision be made for sustaining our entire military force and furnishing it with supplies and munitions of war.

The most energetic and prompt measures and the immediate appearance in arms of a large and overpowering force are recommended to Congress as the most certain and efficient means of bringing the existing collision with Mexico to a speedy and successful termination.

In making these recommendations I deem it proper to declare that it is my anxious desire not only to terminate hostilities speedily, but to bring all matters in dispute between this Government and Mexico to an early and amicable adjustment; and in this view I shall be prepared to renew negotiations whenever Mexico shall be ready to receive propositions or to make propositions of her own. . . .

Conversation-based seminars for collegial PD, one-day and multi-day seminars, graduate credit seminars (MA degree), online and in-person.