“Teachers need to build relationships with students. That’s what I’m good at,” says Amy Parker, who teaches middle school social studies at the Creative Learning Academy in Pensacola, Florida. She attributes her gift for relationships to a childhood spent moving from one Airforce base to another, due to her father’s job as a fighter pilot. “I had to learn to assess new situations and make new friends, quickly ascertaining who would be a positive influence on me and who would not.” Later, Parker worked as a youth leader in a church. “Nothing teaches you about human relationships better than church work. You learn to assess people’s needs.”

Parker also brings to teaching a deep knowledge of American history, informed by her Master of Arts in American History and Government (MAHG) degree, and a gift for engaging students in historical study.

Conversations About Primary Sources

Parker has built a reputation for effectiveness at both the high school and middle school level. For 11 years, she taught Advanced Placement US History at a public high school on Florida’s Gulf Coast. During this time, she was awarded a James Madison Foundation fellowship to cover her Masters work. Taking the advice of other Madison fellows, she enrolled in Ashbrook’s program. As a one who grounds her own teaching practice in relationship-building, Parker found the MAHG program’s seminars congenial: they all involved conversations about primary documents. Her professors and fellow students became friends whom she could “bounce ideas off of.” She gained a broad repertory of primary sources to bring into her own classroom, displacing the textbook.

Her students liked reading and assessing the actual words of historical figures. They responded when Parker said, “I’m not asking you for someone else’s opinion; I’m asking for your own opinion of what you read. How does it fit with what you know was happening in America at the time?”

When Success Brings an Impossible Challenge

Student performance rose, reaching a 90 percent pass rate on the APUSH exam. But Parker’s effectiveness brought a perverse reward.

“Students wanted to be in my class,” Parker said. Administrators assigned her as many as her room would fit. Because they are college-level, advanced placement courses need not follow class size limits set by the Florida legislature. Moreover, in Florida, “schools are awarded money based on the number of students” who take AP classes. Additional funds are awarded for every student who passes the AP exam. Soon Parker had between 35-45 students per class sessions with some up to fifty students in each.

To prepare for the essay questions on the revised AP exam, students need constant practice in writing. “With so many students, I needed to read the equivalent of War and Peace every week to get through all their writing—without a planning period in which to do it,” Parker said. “I had to limit the amount of writing they did.” Her students’ pass rate declined to 70 percent—still well above the national average of 45 percent, and still high enough to bring the school increased funding. Yet Parker felt she was letting students down.

A Sabbatical—and A New Beginning

She resigned from her teaching job and began working as a legal assistant in a law office. The work was pleasant and stress-free. Still, after a year away, she missed teaching young people. She missed designing lessons and collaborating with colleagues. Then the principal of a small private school offered Parker a return to her calling.

The Creative Learning Academy “hired me because of my Master’s degree from Ashland University, because of my reliance on historical documents and because of my knowledge of history and government,” Parker said. Her skills matched the school’s mission: teaching students to read complex texts, think creatively, and solve problems. The school’s principal—whose own children Parker had taught—recognized Parker’s creative energy. She invited Parker to redesign the history curriculum for the sixth through eighth grades.

Presenting American History Through Multiple Lenses

Parker introduced primary documents into sixth grade World History, laying the groundwork for students to read and analyze American historical documents during seventh and eighth grades. “In 7th grade, we study the Revolution and the Founding in the first quarter. My students read all of the primary sources that my high school students read, from the Loyalists to the Patriots. I haven’t lowered my expectations,” Parker said. These first nine weeks give students “a concept of the founding freedoms.” In the next three quarters they study “the challenges to assuring those freedoms.” They read primary documents in African American, women’s, and immigration history.

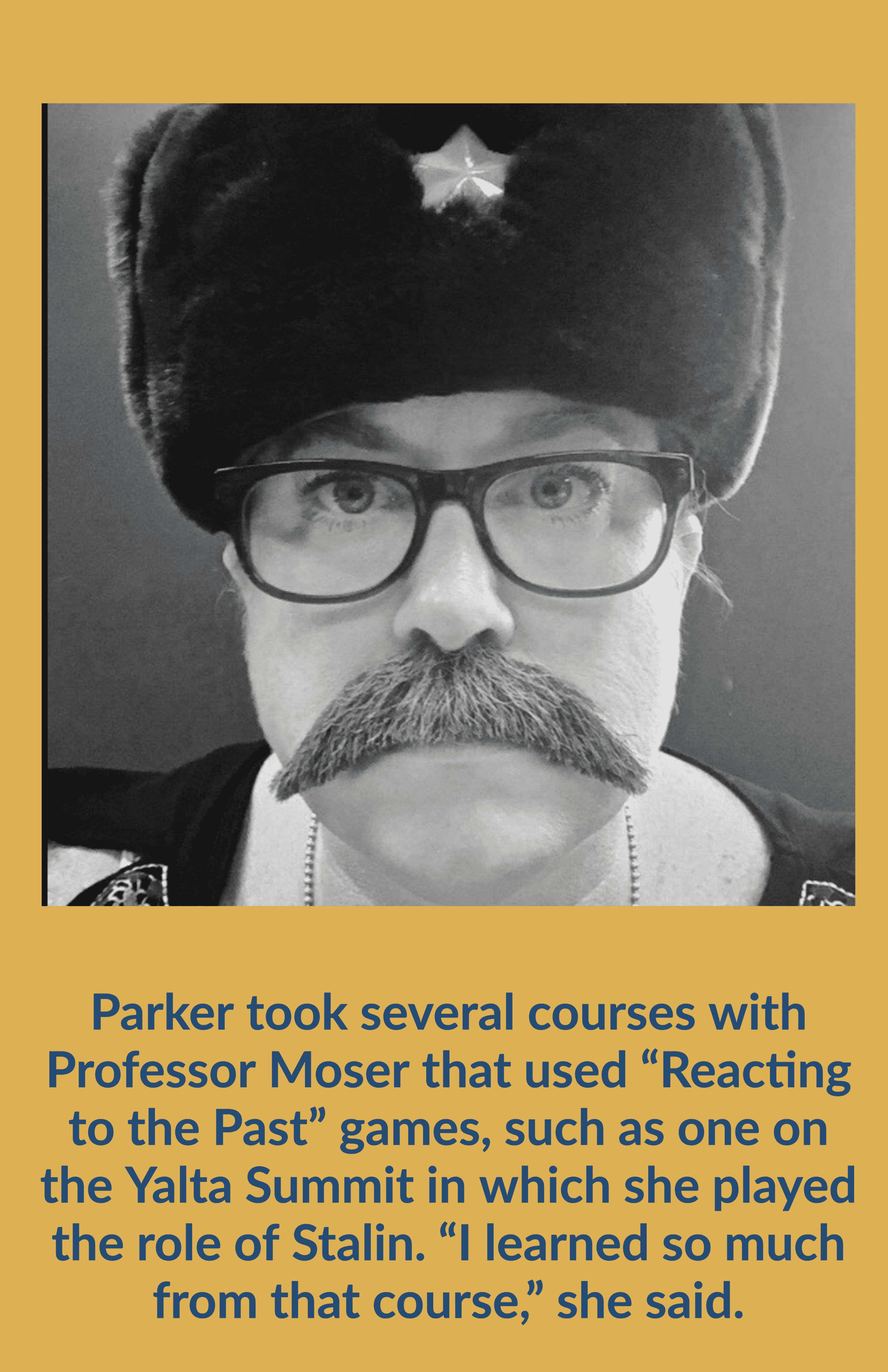

In the eighth grade, students return to the Founding in the first quarter, reading documents that prepare them to study American foreign policy during the rest of the year. Parker drew inspiration for this course from Professor John Moser’s MAHG class in American foreign policy. “We work our way through all the documents that Moser taught. The kids wrestle with them just as we did. They read them with their parents; they talk about them in class and draw conclusions.”

The Teaching American History online library provides Parker the documents she uses in teaching. She particularly appreciates the edited Core Document Collections. “I find the short document introductions super helpful. I don’t have to worry about the reliability of documents in the TAH library—they haven’t been simplified to conform to assumptions about students’ reading level. TAH presents many documents in their entirety, and Parker prefers to teach them that way.

She “preloads” document analysis with practice in difficult vocabulary. Parkers finds that “students rise to your expectations. My students tackle complex texts, and they are better for it. The intellectual jump between middle and high school isn’t so enormous.” Parker’s students finish eighth grade ready for the breadth and detail of chronological history courses, having “looked at American history through several lenses.”

The Relationship Between Teachers and Students

Parker’s school was in the middle of spring break when the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 caused school campus closures. As she revised lesson plans to put them online, she didn’t worry about her students’ ability to analyze documents while studying at home; she knew they were well prepared. To keep home-bound students engaged, she planned Zoom discussions and “virtual fieldtrips” to the websites of National Parks and museums. She felt positive.

Later, she realized she’d been “ill-prepared for the intense emotional swings associated with ‘distance learning.’” Like many other teachers, she’d parted from students without knowing that their classroom time together had already ended. She worried about their emotional health while sheltering at home with parents who might be under stress. “The best part of each week was seeing my students in our Zoom classes,” she said. Yet those encounters left much unknown. In normal times, Parker “can tell if a student is having a bad day the moment they walk into my classroom.” Reading body language through a computer screen is much more difficult. It’s also harder to scan students’ faces for looks of perplexity or sudden insight.

Anticipating another COVID-19 outbreak in the fall of 2020, Parker planned to prepare the next year’s students for a repeat of distance learning—before they left the school building. She’d demonstrate the online platforms they’d use and explain that distance learning meant no relaxation of expectations. She’d prepare students for an uncertain future by building alliances with them aimed at learning. To Parker, “the relationship between teachers and students is at the heart of everything good about education.”