Meet Our Teachers

Rebecca McGinnis

When Rebecca McGinnis chose the recurrent cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century as the focus of her Master’s thesis, she saw it as way to understand the history of her hometown—Circleville, in Pickaway County, Ohio—and of the Ohio and Erie Canal system that connected the county to markets in Cleveland and beyond. She did not imagine her thesis would provide her a framework for understanding a new pandemic, one that that gripped the entire nation in March of 2020.

An International Team Begins Research in Central Ohio

McGinnis was looking for a thesis topic when she visited a local archaeological dig at an abandoned cemetery southwest of city limits. The excavation team, members of the Institute for Research and Learning in Archaeology and Bio-archaeology (IRLAB), had invited local educators to come and observe their work. McGinnis quickly grew fascinated.

Known locally as “the Harrison Township Cholera Cemetery,” the burial site had been established in 1804 by the earliest settlers in the area, but ceased being maintained a few years after the burial of victims of an 1849 cholera outbreak. Before the cause of cholera was well understood, fearful communities often abandoned the burial sites of victims, fearing that vapors from the ground transmitted the disease.

IRLAB’s excavation work aims at reconstructing an unrecorded epidemiological history, with the ultimate aim of learning more about the disease itself, in hopes of improving modern efforts to prevent and treat the disease.

Talking with the head of the excavation, McGinnis heard his “frustration over the lack of historical research on cholera in the area.” McGinnis offered to help the investigators by undertaking the historical detective work. She had found her thesis topic.

Hearing a Need, Finding Direction

It was not the first time McGinnis found direction by paying attention when others pointed out a need.

Entering college, she had declared a political science major, intending to run for office. During an early course in her major, her professor detailed the intense and often antagonistic relationship between local politicians and the reporters who cover them. Thinking, “That is not a battle I want to fight!” she headed to her next class, in geography. “There, the professor veered off topic,” McGinnis said. “He said, ‘Some of you love history and love people, so you think your calling is to be politicians. Actually, you should become teachers.’ I went straight upstairs and changed my major to secondary school social studies,” McGinnis recalled.

Her professor was right. McGinnis enjoys her job at New Hope Christian Academy in Circleville. At the small school, she prepares lessons for six different courses, teaching fifty students a year, most of them several years in a row. She’s discovered a passion for history, intensified by her work in Ashbrook’s Master’s program. “The continual analysis that MAHG pushes you to—it’s contagious; I want to share it. So, I take it back to the young historians in my classroom.” She told her students about her meeting with the bio-archaeologists and reported to her students each clue she uncovered.

Tracing the Local History of Cholera

Little was known about those buried at the excavation site. Headstones had been vandalized and shifted from their original places. Some evidence would come to light as the archaeologists uncovered markers buried under several inches of topsoil and vegetation, but it was fragmentary.

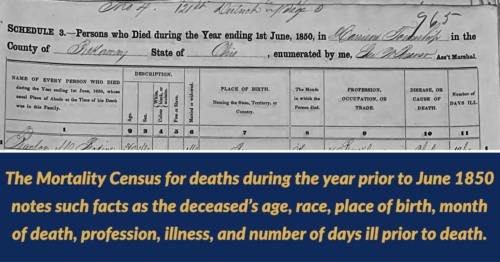

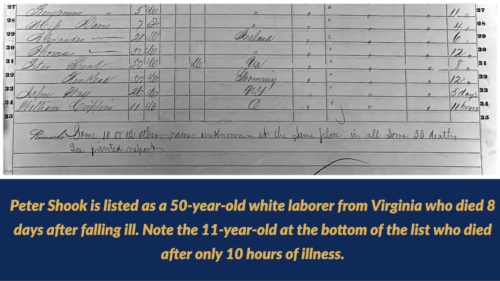

To begin, McGinnis used a cemetery record that a local citizen put together in 1998. He had found the names of 14 of those buried. “I went to Ancestry.com, trying to figure out who those people were, and whether there was any evidence of them dying of cholera,” McGinnis said. She found no clues until she reached the last one: Peter Shook. His name, along with those of 33 others, appeared on a federal mortality census for 1850.

In newspaper archives at the Western Reserve Historical Society in Cleveland, McGinnis found stories of a cholera outbreak in 1849 on a large farm owned by the Renick family. The Renicks grew broom corn for shipment to eastern markets via canal; most of the 33 deaths on the mortality record occurred among the immigrant farm laborers they employed.

One newspaper said the outbreak began when improperly stored potatoes were served as part of the workers’ dinner. (Most likely, water contaminated with the cholera bacteria had mixed with the potatoes, although this was not understood at the time.) When those who ate the potatoes fell ill with diarrhea, the farm owner quickly deduced the cause and ordered the potatoes destroyed; yet those infected were already falling dead. Cholera’s victims often died within a day of first showing symptoms.

Through Ancestry.com, McGinnis connected with a descendant of Peter Shook who told his story. Shook built locks on the Ohio and Erie Canal, a branch of which curved south and east around the Renick farm. He disembarked from a barge to help bury those dying at the farm. Falling ill himself, he was “buried in a grave he had dug.”

These details linked the cholera victims in the cemetery to the nearby canal, a connection IRLAB’s researchers suspected. Circleville’s early leaders had financed the routing of the canal by Circleville, bringing the town commerce and prosperity—but later disease. The stagnant water in the canal system proved to be a vector of cholera.

How Communities Across America Responded to Cholera

McGinnis went on to study the response of communities in Ohio and across the US to cholera outbreaks. One of the first occurred among immigrants arriving in Cleveland in 1832. The disease spread rapidly in the quickly constructed dwellings of single immigrant men, many of them Irish canal workers. Alarmed residents attributed the outbreak to the dissolute habits of these men, many of whom drank freely. As the disease spread through the canal system to other communities, newspaper editorialists frequently assured residents that infection could be avoided by avoiding alcohol and maintaining personal cleanliness.

Even after midcentury, when people began to understand that cholera outbreaks could be prevented by proper sewage disposal, many still accused cholera’s victims of inviting the disease through loose living. At the same time, an unspoken awareness that all were susceptible led many residents to flee town when cholera arrived.

McGinnis traces a connection between the present condition of “cholera cemeteries” and the response of communities to the epidemic when it occurred. In communities where residents “responded with panic, prejudice, and the blaming of victims, the record of where those victims are buried is lost, and their graves are unmaintained.” In communities whose residents “responded with courage, determination to stay put, and concern for their neighbors, cemeteries have been maintained as memorials, and the locals remember the history of the event.”

IRLAB’s work offers Pickaway County “a chance to restore the legacy of the cemetery,” McGinnis notes. “We can be critical of those disturbing a burial place, or we can come alongside them and ask, ‘why do you find this work so important?’ Of all the places in the world they could have gone, here they are among us, wanting to bring our local history to light.” After carefully reburying the excavated remains, the researchers hope to coordinate with local leaders in fencing off the site and providing an historical marker acknowledging the contribution of the immigrant farm laborers and canal workers to central Ohio’s early prosperity.

The Lessons of History

McGinnis was writing her thesis conclusion when COVID-19 led to shelter in place orders and the closing of school campuses. She sees parallels between the history of cholera and the current medical emergency. Cholera—which first appeared in India in 1817—was unknown in the US before trade brought it to Europe and human migration brought it to our shores. It spread across the world as a slow-motion pandemic, flaring five times in Ohio alone between 1832 and 1877. Outbreaks were “handled at the local level, because there are so many variables causing them,” McGinnis says. Similarly, much of the corona virus response has been managed locally. Americans are debating the wisdom of this. The virus’s extended incubation period, combined with the rapidity of current transportation, has caused it to spread much more rapidly than cholera. Yet, since densely populated areas have suffered far more than rural areas, many Americans are more comfortable with local disease management.

To McGinnis, it’s more important to draw moral lessons from the history of cholera. Today’s “essential workers” remind her of the canal workers of the 19th century; they should be honored. Others should show courage. “I don’t want to be the neighbor who remains behind the door, looking through the blinds. I can go get groceries for the elderly, or let an older shopper step in line ahead of me, to reduce their exposure. Sometimes doing the right thing requires ignoring recommendations that keep you safe.”

During cholera epidemics, “the good Samaritans knew you could get up for breakfast and be dead by dinner. But they still helped their neighbors.” McGinnis reminds students that today’s citizens “determine what happens next” in history. Those with “hope in their community’s future” will more likely act courageously.