Meet Our Teachers

Sean Brennan

“We are a nation of immigrants,” says Sean Brennan, who teaches US government at Brecksville-Broadview Heights High School in Broadview Heights, Ohio. “Most of our families came here legally, and most American immigrants still do.” Concerned that students don’t understand the careful process through which immigrants become citizens, Brennan borrowed an idea from a colleague he met at a George Washington Teacher Institute workshop at Mount Vernon, Virginia. He arranged for his high school to sponsor a naturalization ceremony.

Weekend Colloquia Help Teachers Share Ideas

The colleague who shared the idea was government teacher Dusty Helton of Pigeon Forge High School in Tennessee. (Helton, like Brennan, frequents TAH programs.) Helton had learned during a field trip to the Federal District Court in Knoxville that presiding Judge Pamela Reeves was eager to take naturalization ceremonies out into the community, so that citizens might witness them. Helton offered, on the spot, to host one at his school.

Helton advised Brennan to contact a nearby federal district court to see about doing a similar ceremony at Brecksville-Broadview Heights. Brennan already knew a US District Court Judge personally. Since 2011, Brennan has served as President of City Council in his hometown of Parma. Senior Judge Christopher Boyko grew up in Parma, and Brennan knows the Boyko family well. Every year, when Brennan takes the students in his elective course on American jurisprudence to visit courts at the county, state and federal level in Cleveland, they tour the US District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, and Boyko makes time to talk with Brennan’s students.

Helton advised Brennan to contact a nearby federal district court to see about doing a similar ceremony at Brecksville-Broadview Heights. Brennan already knew a US District Court Judge personally. Since 2011, Brennan has served as President of City Council in his hometown of Parma. Senior Judge Christopher Boyko grew up in Parma, and Brennan knows the Boyko family well. Every year, when Brennan takes the students in his elective course on American jurisprudence to visit courts at the county, state and federal level in Cleveland, they tour the US District Court for the Northern District of Ohio, and Boyko makes time to talk with Brennan’s students.

Brennan’s experience as an elected official gave him the confidence to reach out to the federal district court, yet Helton’s example shows any teacher could do the same. And without the networking that goes on at teacher colloquia, Brennan would never have had the idea.

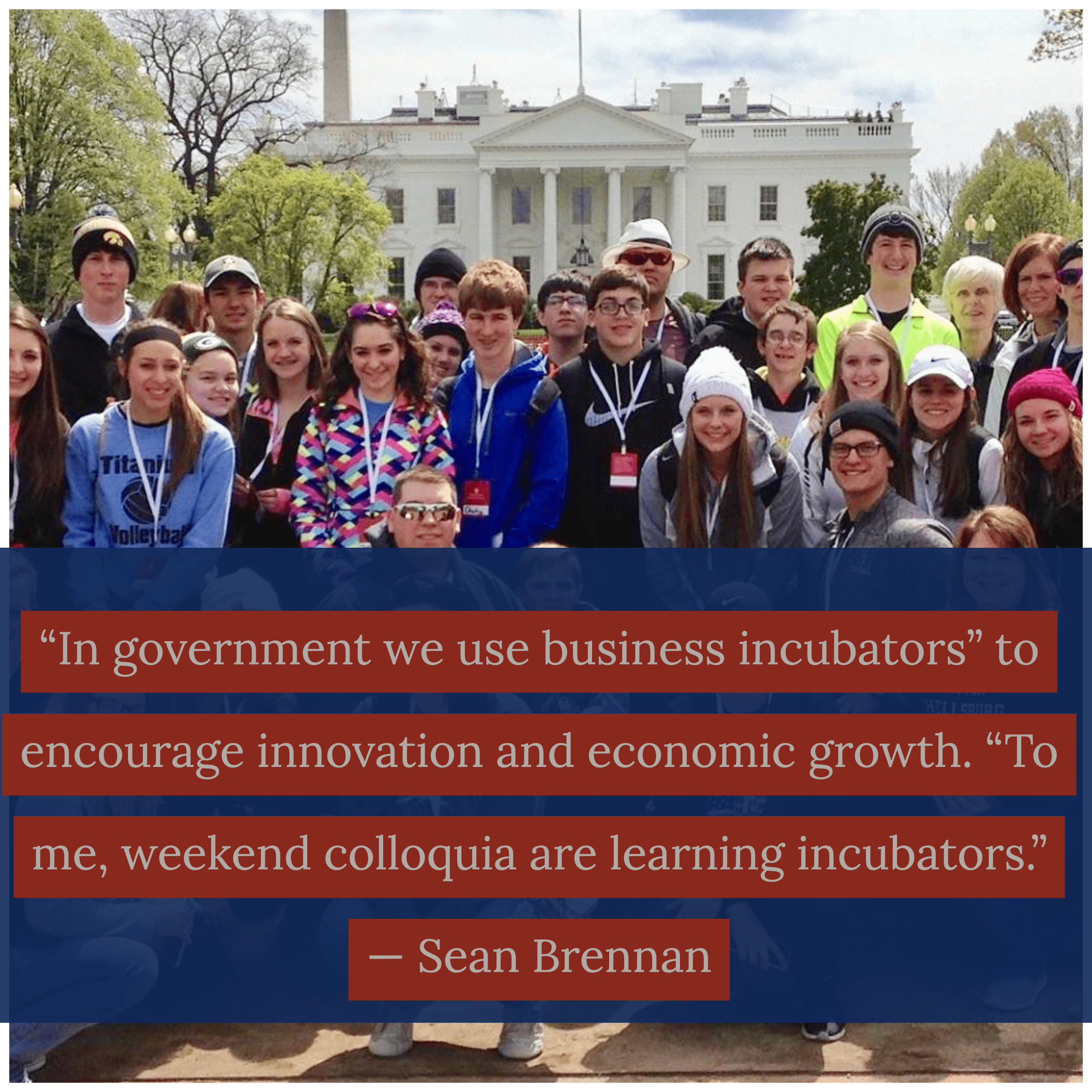

“In government we use business incubators” to encourage innovation and economic growth, Brennan observes. “To me, weekend colloquia are learning incubators.” Teachers meet “with scholars from all over the country and with colleagues who are really, really serious about learning, improving their craft, and passing down the story of our nation to younger people.” The seminars on primary documents get his brain “brimming with ideas;” then, during break periods, “I pick other teachers’ brains for things they do in their classrooms.”

High School Students and Staff Welcome the New Citizens

With the approval of his principal, Steven Ast, Brennan approached the scheduler for the US District Court and found them quite willing to “take their immigration ceremony on the road.” The first naturalization ceremony at Brecksville-Broadview Heights occurred last spring. A second occurred during a school assembly last fall. Staff and students from throughout the school worked to honor the immigrants’ achievement of citizenship.

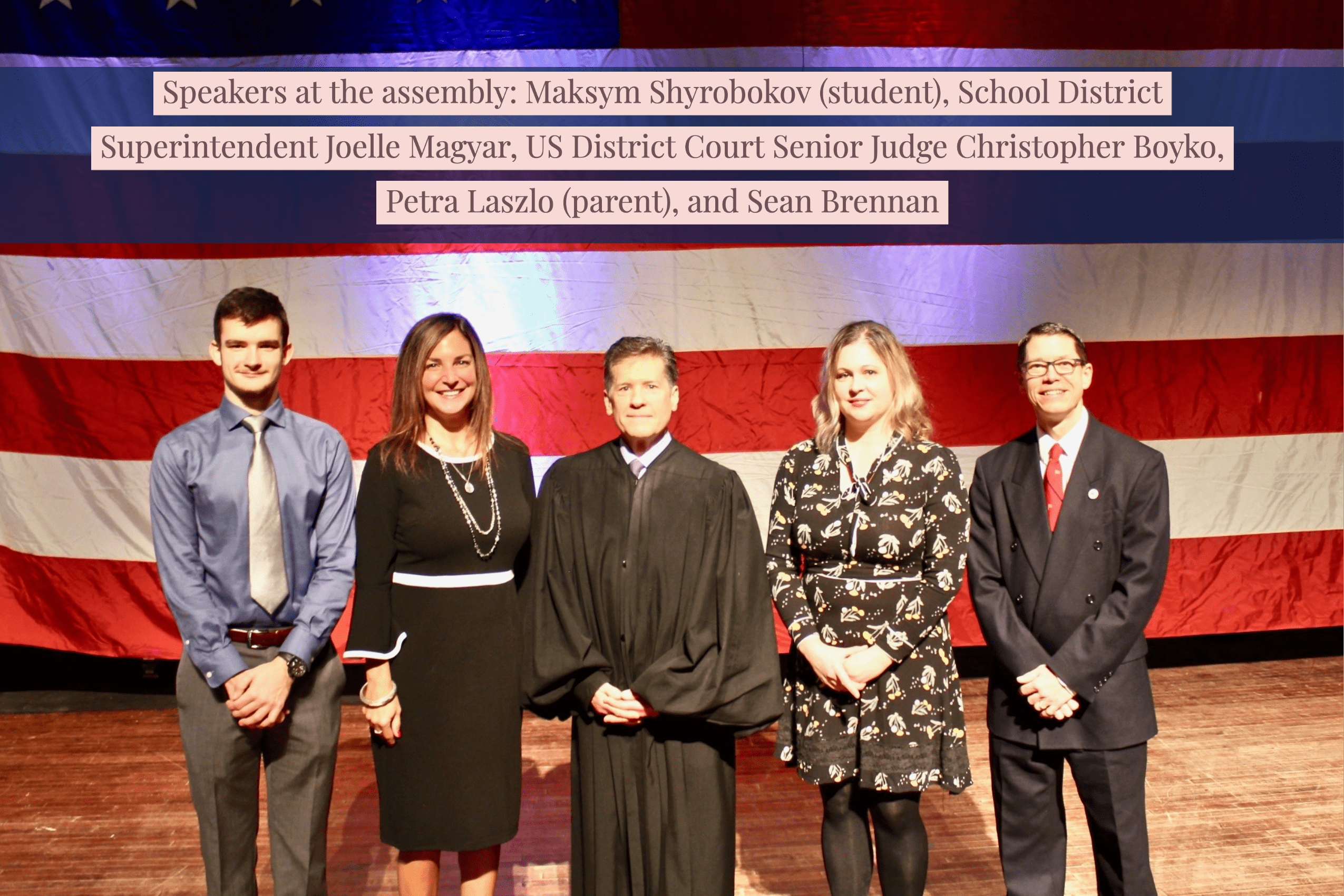

The AP Spanish class welcomed the visitors with refreshments, then escorted them into the auditorium, where an enormous American flag spanned the back of the stage. The choir sang the national anthem. School District Superintendent Joelle Magyar opened the ceremony, thanking the soon-to-be-naturalized citizens for giving students examples of “perseverance, hard work, and our national government in action.” Then the lights dimmed and a film depicting immigrants arriving at Ellis Island played, backed by Neil Diamond’s “Coming to America.”

The AP Spanish class welcomed the visitors with refreshments, then escorted them into the auditorium, where an enormous American flag spanned the back of the stage. The choir sang the national anthem. School District Superintendent Joelle Magyar opened the ceremony, thanking the soon-to-be-naturalized citizens for giving students examples of “perseverance, hard work, and our national government in action.” Then the lights dimmed and a film depicting immigrants arriving at Ellis Island played, backed by Neil Diamond’s “Coming to America.”

What Naturalization Means—to Those Taking the Oath and Those Witnessing It

Speeches detailing the process of naturalization followed. A current student told his family’s story of immigrating to the US from the Ukraine, and a volunteer in the school district’s parent-teacher organization told how her family came to the US from Hungary. Both had learned English in American schools, while their parents found day jobs and studied at night to master English and the facts of civics tested on the citizenship exam.

All new citizens swear an oath of allegiance. They pledge to “support and defend the Constitution and laws of the United States of America against all enemies, foreign and domestic,” to “bear true faith and allegiance to the same” and to perform military or other service when the law so requires. Judge Boyko, himself a second-generation Ukrainian immigrant, led the new citizens in this oath. He also spoke about the gift of liberty and the duty of self-responsibility. In keeping with a tradition of his court, he read “My Creed” by Dean Alfange, a Greek American who declared he came to America “to take the calculated risk; / To dream and to build, / To fail and to succeed.”

Two students in the AP Spanish class (having studied the correct pronunciations of their guests’ foreign names) took turns calling the new citizens to the stage, where Judge Boyko handed each a certificate of naturalization. Boyko and Brennan encouraged each new American to register to vote. Volunteer registrars were standing by at the back of the auditorium.

“I can’t tell you the number of students who told me that was the best school assembly they’d ever been to,” Brennan said. Before, “some of them didn’t even know what naturalization was! Now they will never forget.” Brecksville-Broadview Heights plans to sponsor a yearly naturalization ceremony, with juniors and seniors at the high school witnessing it twice before graduating.

America Welcomes the Persecuted

To Brennan, the naturalization process extends America’s welcome and protection to victims of tyranny and persecution. In his speech at the assembly, he quoted a primary document he discovered in a seminar co-sponsored by TAH and the Loeb Institute for Religious Freedom: George Washington’s letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island. The Jews of Newport had fled persecution in Europe, finding safety in the colony Roger Williams founded as a refuge for the persecuted. Immediately after the Revolution, they sought President Washington’s assurance that their liberties were secure. Brennan read from Washington’s reply:

The citizens of the United States of America have . . . given to mankind . . . a policy worthy of imitation. All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship.

It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

When acts of violent bigotry appear in the news—as when a lone gunman attacked a synagogue in Pittsburgh in October 2018—Brennan teaches this letter. He wants students to understand such acts are deeply un-American.

He hands out copies of Washington’s original version, penned in elegant longhand. Students object, “We can’t read this!” Digital learning has displaced practice with cursive script. Brennan remembers TAH professor Gordon Lloyd worrying that rising generations of scholars will struggle to parse handwritten primary documents. So Brennan tells students, “You can read more than you think you can.” They work in pairs to slowly piece out the words, absorbing more meaning than if they were reading quickly.

Giving Time to What’s Important

Such exercises take precious time in the one-semester government course Ohio law mandates for high school seniors. Brennan, who uses primary documents and a pocket Constitution as his textbooks, wishes he could spend a full year with students. Nevertheless, “every one of my students meets or exceeds their end-of-semester growth target. I always tell kids, if I had a year with you, you’d be running for office yourself.”

City government also requires resource discipline. “Challenging budgets” limit government’s reach, “but you don’t need government to do everything. I’ve worked with others to raise the money” for projects, “instead of using taxpayer funds.” He’s helped initiate a scholarship fund, a 5K run for charity, and a “peanut butter drive” for a local foodbank. Brennan brings to each venture the optimism he sees in generations of American immigrants: “You can’t be afraid of failure. You have to take that risk. And usually, it works out.”