How Did an Expanding Frontier Shape American Culture?

During the summer of 1893, a young historian presented a paper to the American Historical Society on the site of the World’s Columbian Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair. Frederick Jackson Turner’s essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” pointedly noted an announcement by the Census Bureau in 1890 that a western frontier as such no longer existed in the United States, since the entire continent had now been settled. Turner went on to explore what the fact of an expanding frontier had meant in the first century of the republic’s development, drawing large conclusions about the frontier’s effect in shaping a distinctly American individualism. Turner argued that the virtually free land of the west had provided opportunity and diffused social discontent; that in traveling west, Americans had shed many European cultural traits and shaped new ones, partly borrowed from native Americans; and that the necessary self-sufficiency of westward-moving settlers inclined them to devalue central governmental authority. He left open the question of how the nation would adapt to the closing of this frontier.

Turner’s essay—published in the Report of the American Historical Association for 1893 and later incorporated in his 1920 book, the Frontier in American History—profoundly influenced American historiography in the early 20th century. Many of Turner’s claims are currently disputed (for example, his claim that the long struggle to resolve the problem of slavery did less to shape the nation than did the frontier). Nevertheless, the essay still provides an informative summary of the process of western settlement, while raising interesting questions about American self-understanding.

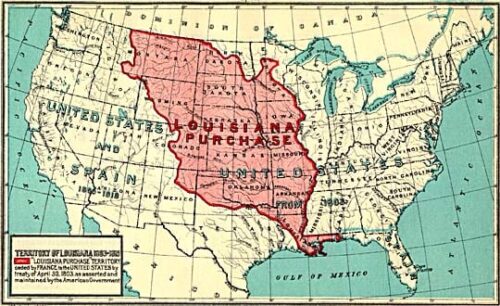

It is interesting to compare Turner’s retrospective view of westward expansion with the prospective view of Jefferson, an early and active proponent of western settlement. In 1783, two decades before pushing through the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson had broached the idea of an exploratory party into the west with George Rogers Clark. He would eventually recruit Clark’s younger brother William to make the trek with Meriwether Lewis, secretly requesting funding from Congress for the expedition in January 1803–three months before he would learn that the ambassadors he had sent to France (James Monroe and Robert Livingston) had been able to negotiate purchase of the entire Louisiana territory.

Seeing in America “an immensity of land courting the industry of the husbandman,” Jefferson rejoiced in Query 19 of Notes on the State of Virginia that the majority of American citizens could live for generations as small yeoman farmers, not as artisans crowded into cities. Jefferson thought the “manners and spirit” of the small farmer best suited to “preserve a republic in vigour.” The speed with which the continent was peopled surely would have surprised him. But Jefferson correctly anticipated the hunger of Americans for western lands, as well as the importance of the trans-Mississippi lands for American strength and security, as seen in his letter to John Breckinridge on August 12, 1803, where he describes his aims in purchasing the Louisiana territory.