335 Year-Old Antislavery Arguments

In 1700, a Puritan judge named Samuel Sewall published the first anti-slavery pamphlet in North America. It was titled “The Selling of Joseph,” and this pamphlet made several arguments against slavery, all based on interpretations of the Bible. Sewall knew his audience: Puritans justified or condemned political decisions based on theological reasons, and Sewall hoped to show his fellow New Englanders that the bulk of Scripture condemned holding one’s fellow man in bondage. In one of his most powerful arguments, Sewell quoted God’s stern prohibition on manstealing – in other words, kidnapping people in order to enslave them. In the Old Testament, manstealing carried the death penalty: “Whoever steals a man and sells him, and anyone found in possession of him, shall be put to death” (Exodus 21:16).

Sewall’s argument did not convince enough Puritans to change New England’s laws. He was opposed in particular by those who were profiting from the slave trade. Proslavery Puritans pointed to verses in the Old Testament that permitted the ancient Israelites to enslave heathen members of foreign nations (e.g. Leviticus 25:44–46). Proslavery Puritans contended that Africans were heathens, and therefore should be treated as the ancient Israelites treated their own heathen neighbors. Moreover, the argument went, enslaved Africans were likely deserving of slavery because they were only enslaved after being taken as prisoners of war. And even if slavery itself was a less-than-ideal status, proslavery Puritans pointed to the (supposedly) harsh conditions of life in Africa in order to promote enslavement as a means of civilizing and caring for unfortunate darker peoples.

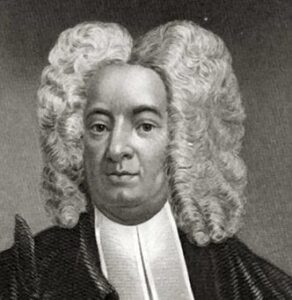

One reason why Samuel Sewall’s attempt to change Puritan attitudes on slavery failed may perhaps lie in his own compromise with prejudice. Sewall admitted that racial differences made New Englanders reluctant to free enslaved Africans, since freedom would mean having to share neighborhoods with people of a different race. He therefore focused on ending the importation of new African residents by banning the slave trade, rather than arguing for a wholesale abolition of slavery. But instead of joining Sewall in his opposition to the slave trade, Puritan leaders such as the Reverend Cotton Mather set forth an alternative position for New Englanders to take regarding their human property: so long as enslaved people were treated well, and taught the precepts of Christianity, there could be no real Biblical objection to slavery. In adopting Mather’s approach to the slavery controversy, Puritans sought to reconcile their faith, and their belief in the commonality of all humans before God, with the profitable business of buying and selling people.

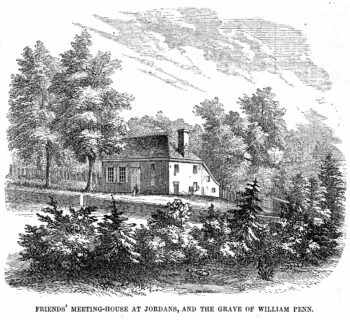

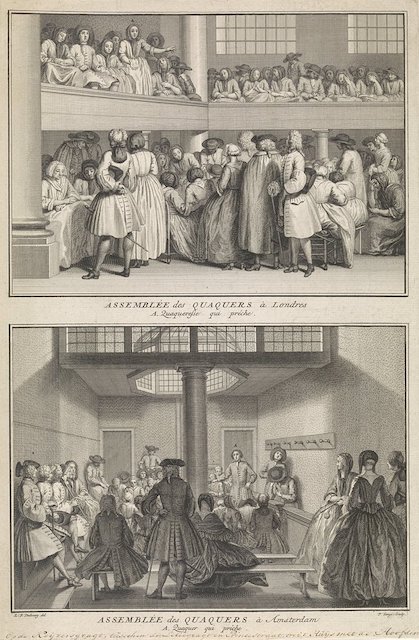

The Puritans were not the only Christians who wrestled with the problem of slavery in the New World. William Penn founded Pennsylvania in 1681 in part to serve as a refuge for Quakers, members of a Christian sect that faced severe religious persecution in Europe. Founded in the early 1650s by Englishman George Fox, the Quaker denomination was known for its embrace of several radical ideas. Among these was the notion that all people, including women, were capable of following the “inner light” of God within them. But while Quakers in today’s popular imagination are rather staid, known for being pacifists or wearing black hats while advertising oats, in the 1600s Quakers attracted controversy because they firmly believed they were acting for God, and that judgment for their enemies was imminent. Because they felt the apocalypse was close at hand, a significant number of early Quakers even welcomed their own martyrdom by defiantly and publicly continuing their controversial, fire-and-brimstone preaching.

By the 1660s, however, the radicalism of the first generation of Quakers had begun to subside. Realizing that the apocalypse was not, in fact, close at hand, Quaker leaders began to emphasize their commitment to pacifism and to create systematic teachings for Quaker congregations—known as “meetings”—to follow. In contrast to the more hierarchical structure of Puritan churches, Quaker meetings consisted of equal participation by all. Silent contemplation was broken when an individual felt he or she had received divine guidance, which could then be shared with the group.

Like the Puritans, the Quakers wrestled with the problem of slavery in the British American colonies. In 1688, the first sign of concern took the form of a “Minute,” or petition, primarily written by a recent immigrant to the Pennsylvania colony named Francis Daniel Pastorius. Pastorius was a young German lawyer who had helped to found the village of Germantown, which is now part of Philadelphia. Together with three other recent German immigrants, Pastorius framed a faith-based argument against slavery. It was first read at the local monthly meeting of Quakers, then sent on to the Quarterly and Yearly meetings in Philadelphia, PA and Burlington, NJ. The Yearly meeting records indicate that the petition was then sent on to London, to be debated by the larger group of Quakers there, but no evidence has been found that any action was taken on this particular petition.

Still, the “Minute Against Slavery, Addressed to Germantown Monthly Meeting, 1688” is an important document in the history of antislavery activism in North America. Within a few decades of its writing, the Quaker sect would become the first religious organization in the world to ban slaveholding among its membership. When the “Minute” is compared to Sewall’s antislavery pamphlet, the reasons why the Quakers beat the Puritans to the abolition finish line become more clear.

Whereas Sewall relied heavily upon specific Biblical stories (such as that of Joseph’s enslavement by his brothers) and Old Testament laws to bolster his case for ending the slave trade, the Quaker petition went right to the heart of the question: “There is a saying that we shall doe to all men like as we will be done ourselves.” This maxim, also commonly known now as the “Golden Rule,” was first given by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount; Jesus told his followers that this ethical standard summarized all the other moral teachings of the Bible (Matthew 7:12). “Do unto others as you want others to do unto you” formed the core of the Quaker petition—after all, “Is there any that would be done or handled in this manner? [for example] to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life?” The Quaker petitioners acknowledged that Africans were racially distinct, but immediately pushed that excuse aside: “tho they are black, we can not conceive there is more liberty to have slaves, as it is to have other white ones.”

After establishing the Golden Rule as the primary reason why slavery was wrong, the Quakers moved swiftly through a list of other objections. Like Sewall, the Quakers pointed to the Biblical prohibition on manstealing, and they also incorporated a similar argument regarding how slavery necessitated the cruel dividing of husbands from wives, thus contributing to adultery. Moreover, because their central thesis was Jesus’s command to “do unto others,” the Quakers asked their audience members to imagine how terrible it would be if they were the ones being stolen away and sold into slavery: “Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries, separating husbands from their wives and children.”

Because the Quakers had emigrated due to religious persecution in Europe, they had an immediate empathy for others who were undergoing oppression. “In Europe,” the petition states, “there are many oppressed for conscience sake; and here there are those oppressed [because they] are of a black colour….Ah! doe consider will this thing, you who doe it, if you would be done [in] this manner?” The powerful return to personal responsibility for other people’s suffering formed the heart of the Quaker petition, and although the Germantown abolitionists did not succeed in persuading their fellow Quakers in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and London to take immediate action on the issue, many other Quakers would soon come to the conclusion that slaveholding was incompatible with Christianity.

The Quakers had banned slavery within their own ranks by the time of American independence, and the group soon became one of the leading voices against slavery in the new republic. The descendants of Puritans in New England followed suit not long after: by 1804, slavery had been abolished in all the northern states. And by 1854, Abraham Lincoln had adopted a very similar argument to that of the Germantown Quakers: “although volume upon volume is written to prove slavery a very good thing, we never hear of the man who wishes to take the good of it, by being a slave himself.”

Cara Rogers is Assistant Professor at Ashland University. She teaches classes on the Enlightenment and the American colonial era. Her research focuses on race and slavery in the Jeffersonian Age.