400th Anniversary of Landing of African Slaves at Jamestown

In late August 1619, John Rolfe tells us that the first enslaved Africans arrived in the English colony of Virginia.

These Africans had been captured from present-day Angola by Portuguese slavers earlier in the year, and their original destination was not Virginia, but Vera Cruz, Mexico. Along the way, however, the slave ship on which they sailed, the San Juan Bautista, was attacked by two English privateers (the White Lion and the Treasurer) who took the cargo – including approximately fifty to sixty enslaved persons – as bounty. The enslaved Africans Rolfe mentions arrived on the White Lion near present-day Hampton, Virginia, in late August 1619, where “twenty and odd” individuals were purchased by the Governor of the colony from the captain of the privateer ship White Lion in exchange for foodstuffs. Shortly thereafter, the Treasurer arrived and sold another group of enslaved persons, including a woman named Angela.

A year later, a colony-wide census indicates a total of 32 Africans (17 women and 15 men) were being held in servitude. Because of their Angolan origins, scholars believe that these first enslaved persons would have been at least exposed to Christianity, if not actually converts themselves. This complicated their status in the Anglo-Atlantic world, which did not initially associate free or un-free status with race but rather with the cultural and religious background of the enslaved person: non-Christians might be enslaved, but Christians could not, and early laws suggested that conversion to Christianity might change one’s status. [For a more detailed consideration of the relationship between race and religion in colonial America, please see our feature on the Moravian community in North Carolina.]

Even apart from the religious dimension, slavery in seventeenth Virginia was not always a permanent and inheritable condition: in the early years of the colony, individual enslaved persons were sometimes able to arrange to purchase their freedom, and policies regarding the status of children born to enslaved persons remained in flux until the 1662.

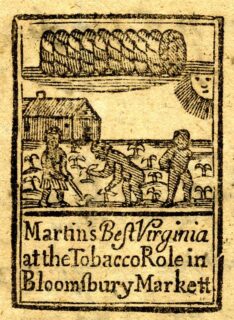

As the story of Anthony and Mary Johnson (documented in Breen and Innes’ “Myne Owne Ground”- Race and Freedom on Virginia’s Eastern Shore) illustrates, it is important to remember that slavery was an evolving system in early America. The Johnsons—both of whom had been brought to America from Africa as slaves themselves – eventually became the owners of a substantial plantation (250 acres) and had servants (possibly slaves) of their own. Virginia’s economic dependence upon the land-intensive crop of tobacco and the subsequent division of the colony into semi-autonomous “private hundreds” or plantations created the social and psychological conditions that made it relatively easy for large landowners to become masters (regardless of race) where the opportunity presented itself. Without the shared institutions and gathering places associated with town living, planters had few reminders to check their pride or ambition and relatively little incentive to see their workers as anything other than resources to be exploited. This psychological tendency was only reinforced when, by the end of the 1670s, black slaves began to replace both white indentured servants and Indian slaves as Virginians’ primary source of labor. By the mid-eighteenth century, the racial dimensions of slavery would be firmly established and even titularly free blacks would face ever-increasing strictures on their rights.

Additional Reading