9/11 — Twenty Years Later, Conclusion

By January, 2002, the US was settling into a conventional approach to the unconventional attack mounted against the US on 9/11. In Afghanistan, where the Taliban routed in eight weeks had not disappeared, in Iraq after Baghdad fell, and around the world, the US military set about finding and killing terrorists. Together with the intelligence community, the military developed an unprecedented degree of proficiency at targeting and eliminating individuals thought to be threats. On the ground, they raided and exploited intelligence very efficiently, and at an extraordinary pace. From the sky, drone tracking and targeting systems stalked and killed our enemies. Together, as we know from captured documents, these hunting and killing systems brought the fear of sudden, violent, unexpected death into the lives of every one of our Islamist enemies.

This killing represented an unconventional tactic put at the service of a conventional strategy. It aimed to destroy the networks of people killing Americans and our soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq, as if they were the military arm of a nation-state. Briefing slides showed the network with the most recently eliminated targets crossed out. The Washington Post featured on its front page a picture of President Obama going over paperwork, deciding who would live and who would die. On rare occasions, we killed U.S. citizens.

But the network on the briefing slides, in truth, depicted not the network, but merely the limits of our knowledge. Every person in the schematic had connections to tens or hundreds of others outside our network diagrams. Killing someone we knew about inside the network affected all of those connections to the network we did not know about. Of course, this is also true in conventional warfare: soldiers have parents, siblings, cousins, and friends. But the logic of conventional warfare puts soldiers at risk so as to protect civilians. When the military is defeated, the war is over. Despite its brutality, conventional warfare is a way of limiting war and the damage of war. Although these conventions tended to break down in the 20th century, they still distinguished conventional from unconventional war. In unconventional warfare, the “network” is not a static military establishment separate from the larger population; it is embedded in that population and part of it. Destroying the part of the network we can see will not necessarily end the war.

Many of those who carried out the in-person raids, as well as some of their political superiors, argued that our network targeting was so efficient and relentless that we would win by attrition: we could kill people faster than they could be replaced, and the network would collapse. This was a version of the conventional attrition warfare that the U.S. military had traditionally carried on. Chris and I had implicitly objected to this view from the first, by presenting an alternative approach. As the war on terror went on, academic and policy debates developed over these different ways to carry on the fight against terrorism.

When I returned to NPS after my temporary work in the Pentagon, I engaged in these and other debates about the war on terror in academic writing, but also in discussions inside and outside class with our students, more and more of whom had tours, sometimes multiple tours, in Afghanistan and Iraq. The special forces officers—who now included officers from our NATO allies, as well as from countries in South and Central America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia—were inclined to accept the arguments in favor of unconventional warfare, just as their colleagues in the conventional forces were inclined to discount them. A few years later, the new Homeland Security Department started a Master’s degree program in homeland security at NPS. I taught in that for several years, learning a good deal from the law enforcement, firefighting, health, cyber security personnel and others I worked with. The early classes especially had numerous representatives from the New York City fire and police departments. Every day, I came to work by driving around obstacles in the approaches to the new gates at NPS. To the armed guards at the gate, I presented my new Department of Defense photo ID card that now carried a chip with additional identifying information.

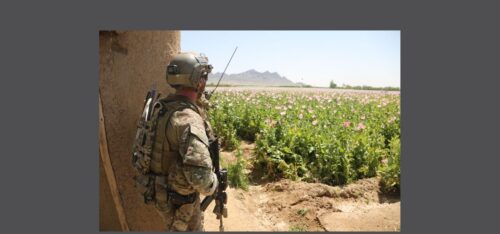

In all the work I did, I presented the same overarching argument Chris and I had made in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. It was directed at two dominant, but (I thought) wrong-headed claims about 9/11 and our response. Some claimed that al Qaeda represented something new and almost impossible to contend with. Information technology, for one thing, enhanced the power of non-state groups like al Qaeda (through online recruiting and propaganda, for example) to a degree that allowed them to threaten the existence of nation-states. Others claimed that we could win the war on terrorism with military force, by identifying and killing terrorists. In contrast to these claims, I argued that in launching the 9/11 attacks, al Qaeda and the Taliban had made a grave strategic blunder. They had raised the conflict to a level at which they could not compete. But this was in the short term. In the longer term—it was a multigenerational conflict after all—this blunder would be fatal only if the United States took advantage of it. Would the US focus on public opinion, intelligence, and politics, rationing its use of force, or make the use of force the leading edge of its response and thereby restore and even strengthen the Taliban and its allies?

Because of or despite what we have done—Afghanistan, Iraq, the Patriot Act, increased security at airports, etc.—we are most concerned today not with Islamist terrorism, but with the political violence and terrorism of the extreme left and right. Still, I find myself thinking back to an earlier time, decades ago when Ellen and I were in the diplomatic service in West Africa. I found myself then on a soccer team composed largely of North African diplomats, with a few others, including a Soviet Uzbek diplomat, thrown in. At some point, three younger, somewhat rougher men became part of the team. They were from somewhere in the Middle East. I assumed Lebanon, since we were posted in a country with a large Lebanese population. What they were doing in West Africa was not clear, although over time I gathered that they were on a sort of R&R tour, staying with cousins, perhaps, resting or hiding out, waiting for the call to go back to whatever they had come from. At first, they didn’t talk to me or even take notice of me. Over time, that changed. I supposed it was because they saw that the diplomats, all Muslims, some from countries with touchy relationships with the United States, seemed to have no problem with the American. Even the Soviet, with whom I was regularly paired at center back, was apparently friendly with me. The younger men never became friendly, only less wary.

I noticed after a while, however, that the member of the trio who seemed to be the leader—a skilled player—was insulting me (I assumed; he spoke in Arabic) for my mistakes as he did all the others on the team. Before one particularly challenging game, he stood poised over the ball at mid-field as we all met there to encourage one another. He turned toward me, grinned and said in an English I did not know until then he possessed, “We are all Muslims today.” I laughed and said “Sure.” He said even louder, almost shouting, “All good Shia!” and we all laughed. We went to our positions, and he put the ball in play.

Not long after that game, the trio stopped showing up. Called back to duty, I assumed. I thought of them occasionally after that, wondering what happened to them. More recently, I have wondered what became of their children, and grandchildren.

David Tucker is the general editor of Teaching American History’s core document volumes. He is the author most recently of United States Special Operations Forces (2020) and Revolution and Resistance: Moral Revolution, Military Might, and the End of Empire (2016). This post draws on arguments in both books.