9/11 — Twenty Years Later, Pt. 1

I don’t remember when I heard the news. The planes hit the north and then the south tower while we in California were still asleep. Flight 77 hit the Pentagon, where I had worked for eight years, ending three years before, at about the time I usually got up. The south tower collapsed and flight 93 crashed in Shanksville, Pennsylvania about the time the kids got up. The north tower collapsed after Ellen left for work and about the time the kids were usually brushing their teeth, collecting their books, and getting ready to head out the door. We lived in a quiet neighborhood. Every week day, the kids walked to their school, a short distance away. They did that morning as well.

I believe Ellen heard the news on the car radio as she drove to work, called me after the kids had gone out the door, and told me to turn on the TV. There I saw the images played over and over again. A bit later, when I drove to my teaching and research job at the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), a graduate school run by the Navy but serving all the services and some civilian agencies as well, I found the school closed. It stayed closed for several days while the Department of Defense sorted out new security arrangements. (Before the attack one could drive onto the NPS campus, or base as the Navy would say, without any security checks at all.) So, I went back home to stare at the images on TV still wondering if my former colleagues in the Pentagon were alright and what the attacks would mean for our students. (I taught in a program sponsored by the Special Operations Command, so our students were officers in the special operations units of the Army, Navy, and Air Force.)

That afternoon, I went to the kids’ school and walked home with them. They and their friends were full of questions. They knew something important had happened, but they didn’t know exactly what. At that point, that was as much as anyone knew.

In the days following the attack, I learned through emails and phone calls that my former colleagues in the Pentagon were safe, as was my former boss and friend, Chris, who had moved on to a new more important job in the Pentagon. Classes resumed at NPS. As always, the officers maintained the calm stoic demeanor of their profession, but I was sure they all knew that their lives had now changed in ways they could not predict.

A short time after classes resumed, Chris called me at home early one morning, asking if I could call him from NPS on a secure line. When I did, he explained that we had an opportunity to influence the ongoing discussion in the Pentagon on how the United States should respond to the attacks. Chris and I had worked together in a Pentagon office, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low Intensity Conflict, that focused on such issues as terrorism and other forms of non-state warfare. In the early 1990s, the office had been created by Congress. It was dissatisfied with how the Pentagon and the U. S. government generally handled conflict and political-military operations (e.g. peacekeeping, counterinsurgency, counterterrorism) that were not conventional, full-scale military conflicts. Because Congress imposed it on the Pentagon, and because the Pentagon’s civilian and military leadership had focused historically on conventional warfare, the office Chris and I had worked in was often ignored in the great doings of the Defense Department.

Using secure communications, Chris and I put together a short paper outlining a response. The core of our argument was that the problem we faced was not primarily a military problem, but an intelligence problem. In World War II the problem was not finding the German or Japanese armies. The problem was defeating them militarily. With al Qaeda, the problem was reversed. Defeating them militarily would not be a problem, but finding them would be.

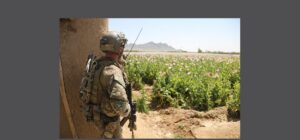

The Taliban government itself was a tribal movement more than a government on the European or American model and its fighting force more a tribal militia than anything comparable to the U.S. military. The rules of conventional warfare, the whole logic of what to threaten with destruction in order to achieve military victory and our political objectives, would not apply, we argued, in the coming fight with the Taliban and al Qaeda, and their allies and potential allies around the world. There would be no equivalent of winning by capturing Berlin.

If this was primarily an intelligence fight, then it was critical that everything be done with public opinion in mind. And the publics involved were various: supporters of the Taliban and al Qaeda in Afghanistan and around the world; the people of Afghanistan; the Muslim peoples of South Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and Southeast Asia; the peoples of Europe; and Americans themselves. Muslim populations were those in which al Qaeda could best hide and from which it drew support. Europe, with a large Muslim population, and all of our NATO allies, would be essential in the coming fight. Even in conventional war, the connection between the use of force and the desired political outcome is often complex. In the conflict that had now begun, it was sure to be complex, and even paradoxical. When our intelligence improved, finding would be easier, especially with the help of the various publics involved, and hence killing would be too, but killing should not be the main objective. Instead, we should focus on keeping public opinion on our side or at least less and less likely to support the terrorists. Over the long term, this would expose and weaken the terrorists, while a focus on killing them was likely to lead to uses of force that could strengthen them. The most powerful or effective use of force was to use less of it. Although the 9/11 attacks were more destructive than any terrorism we had before experienced, they were still best understood, we argued, through the logic of unconventional warfare.

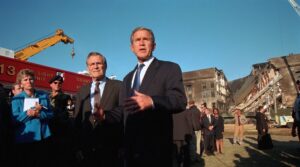

We were encouraged at first, because then Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld cautioned reporters in his many briefings that the conflict would not be like other wars America had fought. It was going to be a generational or even multi-generational conflict. There would be no surrender ceremony as there had been on the deck of the Missouri to end the war with Japan, he said. Rumsfeld was still speaking that way when Chris asked me toward the end of September to return temporarily to the Pentagon to work in his office. I got there just about the time the bombing campaign began on October 7 and stayed several weeks. (The length of my stay has remained a subject of family debate: Ellen, left with the kids and a job, remembers it as a longer stay than I do.)

As we worked on various projects and as time went by, it became clear that the response to 9/11 would be a conventional one. Special Forces went into Afghanistan in mid-October, and to everyone’s surprise but theirs quickly routed the Taliban and al Qaeda forces by coordinating attacks with the U.S. Air Force and the Taliban’s opponents, the Northern Alliance. But Special Forces had been sent only because politics required a prompt response to 9/11, and the conventional military was still some time away from deployment. By the time Kandahar, the Taliban’s birth place and last refuge, fell in mid-December, a conventional force command element had been put in place. From that point on, the approach became more and more conventional.

Afghanistan became a conventional conflict for four reasons. First, that is the habitual way the U.S. military operates. Major conventional warfare is the event for which the U.S. military rightly plans, trains and equips. Second, those running national security and the defense department in the Bush administration were all cold warriors, many of them veterans of the first Bush administration that had brought the Cold War to an end. They had studied and spent their careers on nuclear weapons strategy and the balance of forces at the Fulda gap. More recently, some had worked on space warfare or the revolution that information technology was supposed to be creating in military affairs. Rumsfeld’s claim that this would be a different kind of war did not seem to alter their fundamental outlook. Third, as became clear over time, Rumsfeld himself did not want anything to do with unconventional or counter-insurgent warfare. That sounded like Vietnam and smelled of quagmire and defeat. Finally, like all administrations, the Bush administration sought to distinguish itself from its predecessor. The Bush people discounted what the Clinton people had learned about al Qaeda and terrorism, just as the Clinton people had discounted what the first Bush administration had learned. (Clinton had run against Bush’s policies in Haiti and Somalia, but circumstances forced him to revert to that policy in Haiti. In Somalia, where he did not, he suffered his own debacle in October 1993.)

It would be foolish to think that any particular strategy or approach would necessarily have succeeded, or that another was necessarily destined to fail. Yet, in their efforts to avoid what they thought would be the appearance of defeat, Rumsfeld and the Bush administration may have made actual defeat more likely.

David Tucker is the general editor of Teaching American History’s core document volumes. He is the author most recently of United States Special Operations Forces (2020) and Revolution and Resistance: Moral Revolution, Military Might, and the End of Empire (2016). This post draws on arguments in both books.