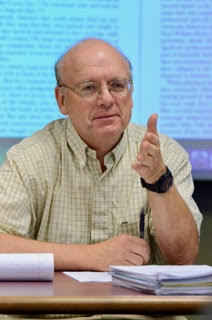

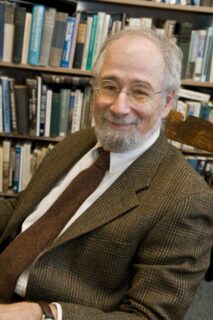

Marc Landy Discusses the 2016 Election

The 2016 presidential election highlighted strong divisions among American voters, while the outcome defied the predictions of pollsters. We asked Professor Marc Landy, a highly respected instructor in Ashland’s Master’s program for secondary school teachers, to talk about what the election means. Landy is Professor of Political Science at Boston College and Edward and Louise Peterson Professor of American History and Government at Ashland University. He researches political parties, the presidency, and American political development. With Jeremy Bailey of the University of Houston, Landy co-teaches a two-part historical survey of the presidency in our summer residential MAHG program.

Landy has written several studies of public policy, including Creating Competitive Markets: The Politics and Economics of Regulatory Reform (2007) and Seeking the Center: Politics and Policymaking at the New Century (2001). With Sidney Milkis, he has authored Presidential Greatness (2000) and a textbook, American Government: Enduring Principles, Critical Choices, now in its third edition (2014).

- Professor Landy, is it accurate to call the Trump campaign a populist movement? If so, how does it resemble or differ from other populist movements we have seen in the US?

If we agree on the definition of populism as a movement of voters very disaffected with the establishment, with the way the “elites” are governing, then certainly this is a populist movement. Two such movements readily come to mind: the Jacksonians in the 1830s and the Populist Party of the 1880s and 1890s. But those movements had very different goals. Jackson was fighting for the decentralization of government. He felt the common man needed a government closer to him than the elites who were governing at the national level. With Bryan, it was a specific set of economic questions that were affecting the farmers.

With Trump, it’s a much broader set of questions: the abandonment of industry in the rustbelt, plus the resentment of those who feel their values are being denigrated by the liberal cultural elite. It’s a very different movement, with more diffused motives.

- Do you feel a “realignment” of the electorate has occurred, favoring the Republican Party? In 2008, some thought that Obama triggered a realignment in favor of the Democratic Party.

You can’t tell. Realigning elections don’t happen when the new political leader first takes power; they happen when that person wins re-election. A great example is FDR. The realignment didn’t occur in 1932; it happened in 1936, when you knew popular support for Roosevelt was real. The same goes for Jackson. It didn’t happen when he was first elected in 1828. The re-election solidifies the new direction.

- What does the election of 2016 teach us about our current primary system? Do you view this system as more “democratic” than earlier processes for selecting candidates? Does the fact that state primaries occur throughout several months, rather than all on the same day, undercut the “democratic” impulse behind the primary system?

Our primary system is dreadful. The idea that there should be a preliminary election before the general election, in order to give the people a decent choice—that seems very wrong-headed. Political parties are a very good idea. Inherent in the party system is the idea that those within the party have more in common than they do with those outside of the party. What the primary system does is to disrupt that feeling of party cohesion, loyalty and commonality.

As for staggering the primaries over a series of months in different states, it’s hard to know how else you could do it. The only other way would be for the party leaders in each state to select delegates who were committed to them, who would meet to hammer out who the candidate would be. But that can’t be done in today’s political climate. So we have to figure out another way to winnow out the candidates. On the Republican side, the fact that we had so many candidates was a disaster. But I don’t know how you could devise rules to limit that possibility.

Some dreadful things just can’t be undone. Right now, I fear that any effort to tinker with the primaries would lead to accusations of election rigging.

- Given that Clinton won the popular vote, many people are again questioning the Electoral College. Does that institution still serve a useful purpose?

I love the Electoral College! It’s a way of affirming that we elect our president via fifty state elections. That reinforces our notion of American federalism, which is very important. Second, it gives a part of the country that otherwise would probably be neglected more prominence. But the essential thing is that presidents are elected by the states; this ensures that the states remain a part of our system of government.

- This election seemed to turn on questions about the character of the candidates more than any other recent presidential election. Is this an accurate historical perspective? If so, why do you think this occurred?

I think we see it in an extreme form in this election. There have been character issues raised in other times: with Nixon, for example. But to have serious character issues raised with both candidates is highly unusual. This again points to the danger of the primary system. Up to now, we’ve been very lucky. We have had few unfortunate choices since the primaries took hold, in the late sixties and seventies. In every case since 1972 (I don’t think McGovern could have succeeded as president) the losing candidate could have governed the country. But this time, the primary system resulted in very unhappy choices.

Clinton would have had as much trouble unifying the country under her leadership as Trump will have. Had Hillary won, her term would have been dominated by investigations of her conduct while Secretary of State. With Trump, we know so little about how he plans to govern, that we cannot predict how he might succeed. Certain things that served him very well during the campaign, emphasizing his outsider status, now make him look unprepared to assume the role.

- Are Congress and the executive likely to cooperate during the next four years? If so, what sort of mandate will Republicans in Congress believe the election gave them?

The initial signs suggest cooperation. The choice of Priebus as chief of staff is excellent, and Priebus as a bridge between Trump and Ryan is promising.

The election does suggest a mandate to do something serious about Obamacare. Trump campaigned hard on it, and Congressional Republicans have made it a high priority over a number of years. The word “repeal” is very misleading; they can repeal the law, but they would have to put something in its place.

- Do you see the American electorate as more divided than ever before? To put the question another way, are the divided sides in this election less tolerant of each other’s views than ever before?

We’re divided in different ways. Today the arm of the federal government reaches further into people’s lives. And the media really penetrates. People in remote areas may be even more affected by the major media outlets than those who live in urban areas, where there are a diversity of news sources.

Many observers discounted the grievances of those in the rustbelt and southern states: their terrible economic insecurity and their resentment of “political correctness.”

It was not so much that people lost jobs; rather, they lost the high-paying factory jobs they once had. They’re working for $15 an hour instead of $20 or $30. Then, people objected to points of view being imposed on them. It’s not that they all object to homosexual or transgender behavior, but they don’t like being forced into positions that they think defy common sense, such as allowing a person who appears to be a male to use a female bathroom. The demonstrations in Ferguson, which challenged people’s notions of law and order, troubled them also. These are serious issues, and the fact that many people felt they were not allowed to discuss them in a reasonable way hurt the Democrats.