Abraham Lincoln and the Struggle over Slavery

Now available in our bookstore!

In 1854, Abraham Lincoln said of Thomas Jefferson that he “was, is, and perhaps will continue to be our most distinguished politician.” We may now say this of Lincoln. And just as Lincoln meant that one must understand Jefferson’s politics and principles—his deeds and his words—to understand the United States, so must we now say that to understand the United States we must understand Lincoln’s deeds and words. We offer this volume as an aid in the effort to understand Lincoln and, through him, what remains the world’s most important experiment in self-government.

This collection offers twenty-six of Lincoln’s most important speeches and writings, each accompanied by an introduction that provides historical context. The most important context was, of course, the struggle over slavery.

Slavery and the Early Republic

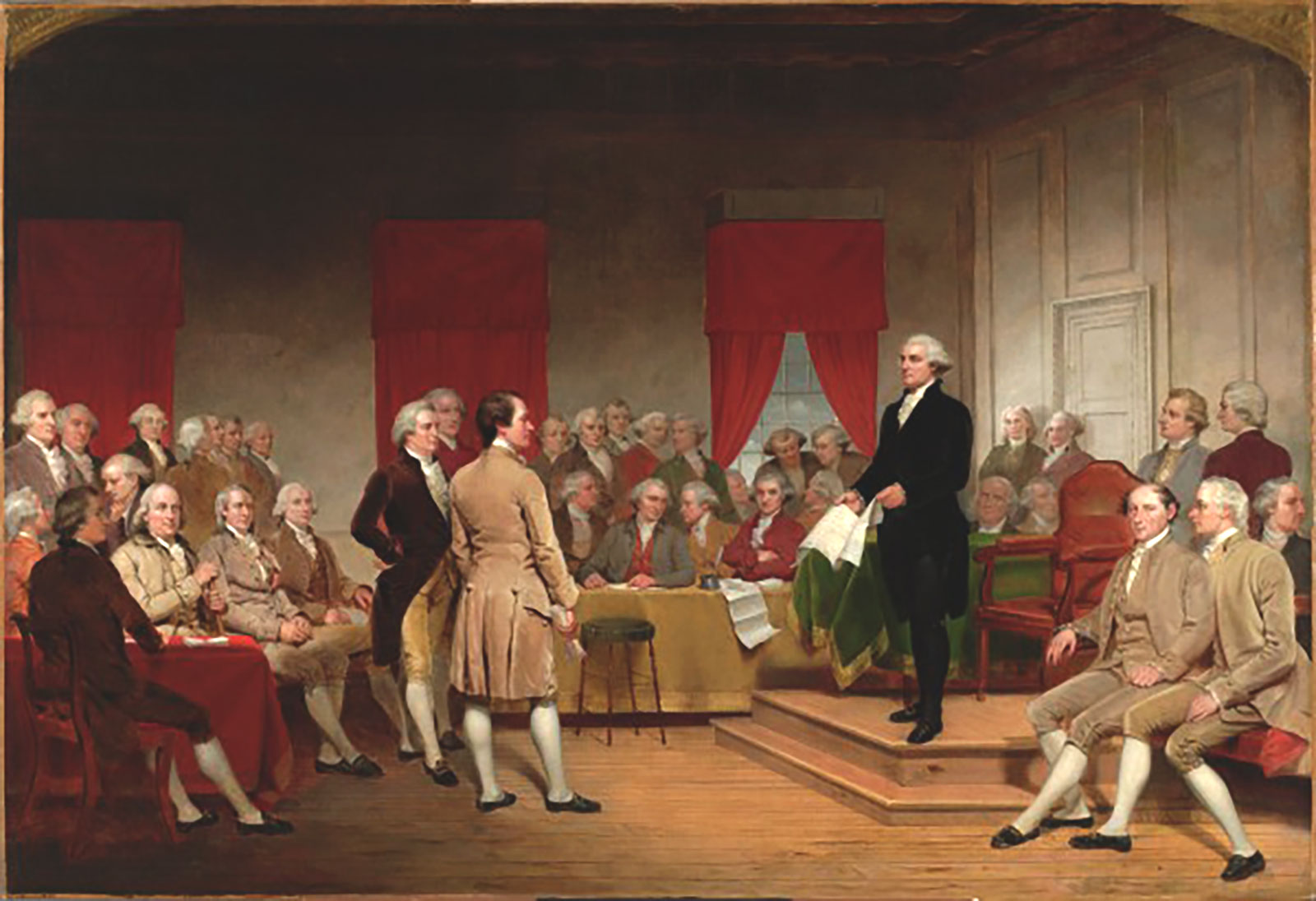

Slavery—and who bore the responsibility for its existence in America—was discussed when the Continental Congress reviewed Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence. Later, those drafting the Constitution included three provisions concerning slavery, without ever mentioning the peculiar institution by name. (At the convention, James Madison remarked that it would be “wrong to admit in the Constitution the idea that there could be property in men.”) First, the framers allowed “all other persons” besides “free persons” and “Indians not taxed” to be counted as three–fifths of a free person for purposes of taxation and representation (Art. I, sec. 2). This was a compromise among the delegates who wanted to count enslaved people when determining a state’s population (and thus the number of representatives in the House of Representatives and Electoral College votes) and those who did not. Second, the Constitution provided that the importation of “persons” by a state could not be prohibited for twenty years after its adoption—until 1808. This was a compromise between those who wanted to ban the importation of slaves immediately and those who wished there to be no prohibition at all on the slave trade (Art. I, sec. 9). In addition to these two compromises, the Constitution also contained a provision that “no person held to service” in one state would be discharged from that service in another. Rather, the Constitution made it an obligation to return such persons to those to whom their labor was due (Art. IV, sec. 2). This provision became known as the fugitive slave clause. To implement it, Congress passed the first fugitive slave law in 1793.

Slavery and an Expanding Country

In 1807, in what Lincoln called “apparent hot haste,” Congress passed a law prohibiting the importation of slaves beginning on the first day of January 1808. Four years before the passage of this law, the United States had acquired the Louisiana territory. After Louisiana was admitted to statehood in 1812, the next territory from this acquisition to apply for admission as a state was Missouri, in 1819, under a constitution that permitted slavery. At the time, there were eleven free and eleven slave states. Missouri was not admitted as a slave state until Maine applied for statehood and was admitted as a free state. As part of this compromise, Congress included in the Missouri statehood enabling act the provision that in the remainder of the Louisiana territory slavery would forever be prohibited north of latitude 36º 30´ N. (Lincoln recounted the history of the struggle over slavery from the founding through the sectional conflict in Document 4, his speech on the repeal of the Missouri Compromise.)

The Mexican-American War and the Fruits of Victory

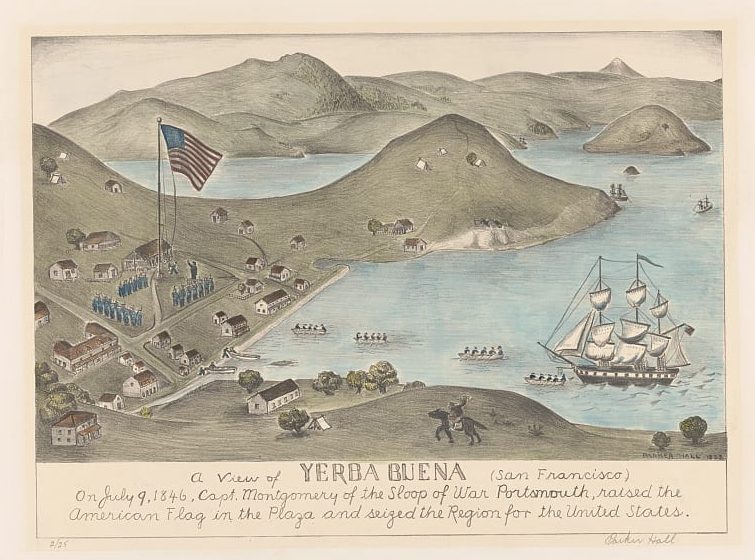

In 1836, Texas separated from Mexico through a revolution and declared itself a separate republic, claiming territory to the west and north encompassing parts of the current U.S. states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico. When Texas joined the Union in 1845, war with Mexico followed (Mexico considered Texas still part of its territory). Early in the war, when President James Polk asked for an appropriation for peace negotiations, Representative David Wilmot (D-PA) proposed an amendment to the appropriations bill stating that slavery would not be permitted in any territory gained from Mexico in the peace negotiations. The bill passed the House but not the Senate. Subsequent versions of Wilmot’s amendment met the same fate. The treaty that eventually ended the war, which had to be ratified only by the Senate, contained no prohibition of slavery. The contest between free state and slavery advocates over this territory and what remained of the Louisiana territory was the final phase of the sectional conflict leading to the Civil War.

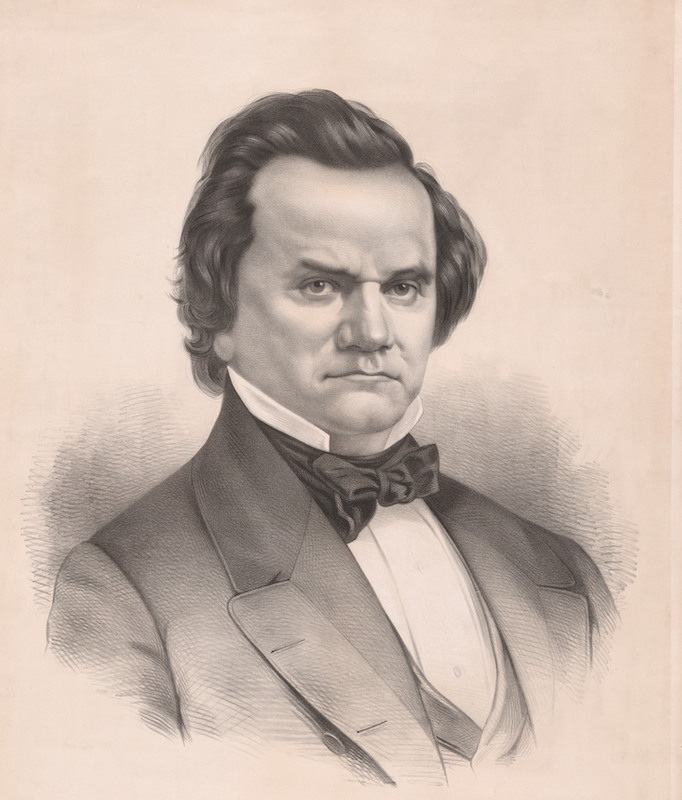

Following the Mexican War, California applied for admission as a free state. At that point, the number of free and slave states was equal (fifteen each). California’s application for admission thus precipitated a crisis, just as Missouri’s had thirty years before. The crisis was resolved by the Compromise of 1850, which consisted of five separate pieces of legislation. Stephen A. Douglas (1813–1861), a Democratic senator from Illinois, was responsible for getting the legislation passed. The bills admitted California as a free state; set the boundary between Texas and New Mexico and compensated Texas for giving up land claims beyond that boundary; set up territorial governments for Utah and New Mexico, with the provision that the territories could eventually enter the Union as either free or slave states; abolished the slave trade (but not slavery) in the District of Columbia; and strengthened the federal fugitive slave law.

Stephen A. Douglas and the Kansas-Nebraska Act

When it came time to organize territories north of Texas that were part of the Louisiana purchase, Senator Douglas again took the lead. In 1854 he proposed the Kansas-Nebraska bill, accepting an amendment that rescinded the Missouri Compromise line of 36º 30´, which was supposed to have been established forever, and leaving the decision regarding slavery to each territory’s inhabitants (Document 4). Douglas called such decision making “popular sovereignty”—the people should decide without the interference of the federal government—declaring it the simplest and fairest way of resolving the controversy over slavery. The bill’s immediate practical result, however, was to foment civil violence. Everyone understood that once slavery became established in a territory, it would receive the protection of territorial law. Thus protected, slavery would grow and become ever harder to abolish. Free state and slave state advocates in and beyond Kansas and Nebraska fought to gain the advantage and determine whether this peculiar form of property would be allowed. As one scholar put it, “the Kansas-Nebraska Act legislated civil war on the plains of Kansas.”

The civil war in “Bleeding Kansas” magnified the sectional conflict and pointed toward the greater civil war that would begin six years later. This conflict became even more likely in 1857 as a result of the Dred Scott decision, in which the Supreme Court held (7–2) that persons of African descent were not citizens and had “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The Court went further and declared that Congress could not prohibit slavery in the territories because the right to hold property in slaves was “distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution.” If the right to hold slaves was in the Constitution, however, did that not imply that Southerners had the right to take their property into any state? The Dred Scott opinion suggested at least the possibility that a future Court ruling might declare slavery to be the national norm, permissible even in those states that had decades earlier declared it illegal.

Abraham Lincoln and the Problems with Popular Sovereignty

Lincoln returned to politics during the controversy over the Kansas-Nebraska act, recognizing the danger to self-government and human liberty should Douglas’ understanding of “popular sovereignty” prevail. If the people in a territory chose to admit slavery—ignoring the Declaration’s assertion that all men are created equal—then they would undermine the principle on which their own freedom was based. Among the people, popular sovereignty was the strongest and the most obvious and easily grasped principle of the Republic. Unlike Douglas, Lincoln through his words and deeds had to show the people that the only thing more important than that principle was its ultimate cause, human equality. More difficult, he had to show the people that preserving their liberty meant restricting their freedom: there were some things that the people could not rightly choose to do.

Civil War Commences

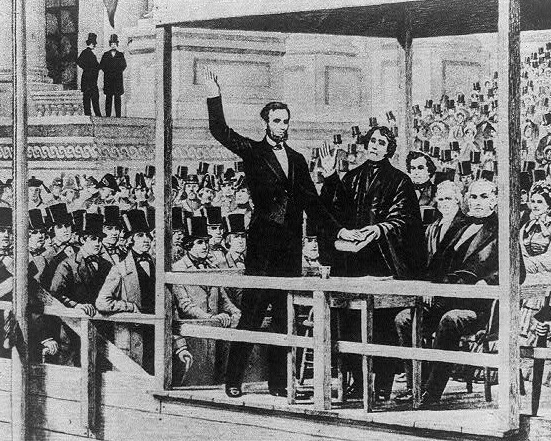

Lincoln won the presidency in 1860 on a platform of preventing the spread of slavery beyond the states where it already existed, and affirming the Declaration’s claim that all men were created equal. Lincoln defeated the other three presidential candidates with a plurality of the vote and amassed more Electoral College votes than his three opponents combined. His election precipitated the secession—as they called it—of seven states, ultimately joined by four others. Lincoln denied that secession was legal or constitutional. The states that claimed to have left the Union were thus in rebellion

What Lincoln could accomplish to end the rebellion and save the Union, which he considered his principal duty as president, depended on four considerations, each requiring his careful attention:

- northern support for the war;

- the opinions of those in the border states (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri);

- the actions toward the rebellious states of foreign powers, especially Great Britain;

- and the success of Union military forces against the rebel armies (Documents 15, 16, 20).

In the North and the border states, opinions on slavery and the Union varied. Some were so strongly in favor of slavery that they were willing to let the Union go to preserve it; others were so strongly opposed to slavery that they were willing to dissolve the Union to rid themselves of it. Still others were unwilling to surrender the Union and were willing to compromise with slaveholders to keep it together. Pervading public opinion, even among antislavery stalwarts, was an unforgiving prejudice against African Americans, evident in the offensive terms that appear in some of these documents. Lincoln, however, understood that preserving the Union ultimately meant ending slavery. Slavery was incompatible with the Declaration’s claim of equality, and the Constitution and the Union existed to serve the Declaration. In everything he said and did to preserve the Union and end slavery, Lincoln took into account the opinions and prejudices of the varied audiences he addressed.

As for the success of Union military forces, for the first years of the war they had little. The tide turned, however, when Lincoln put in command generals prepared to seek decisive victory over Confederate forces. The turning point came first at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in the summer of 1863, and then in the all-important Virginia theater of the war after Ulysses S. Grant (1822–1885) took command (1864) of all Union forces.

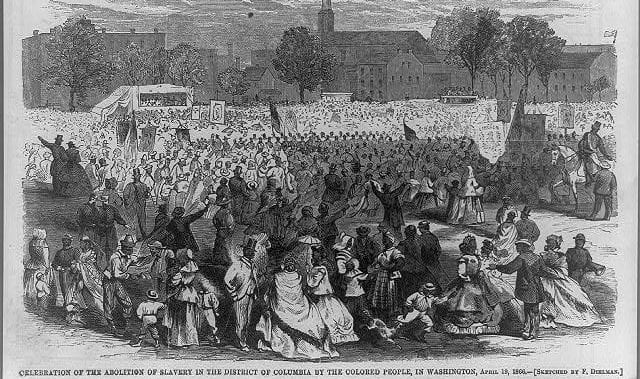

The End of Slavery

The prospect of Union victory raised the question of how to return the rebellious states to the Union. Historically, defeated rebels had received harsh treatment. “Radical” Republicans favored this approach. Lincoln sought a more moderate course, making acceptance of the Thirteenth Amendment (1865) abolishing slavery a requirement for regaining their civil status, and seeking some way to provide for the formerly enslaved. Early in his second administration—just as he was about to embark on the arduous task of reconstruction—Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865.