History through Literature: An Interview with Suzanne Hunter Brown & Jennifer Keene

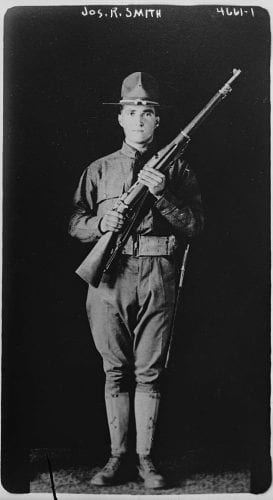

This summer, Suzanne Hunter Brown will join historian Jennifer Keene (Chapman University) to lead a course on the history and literature of the 20th century’s World Wars. Using primary historical documents along with memoirs, fiction and poetry, the course will consider Americans’ battlefield and domestic experience, as well as civil-military relations and the connection between our political principles and our military practices.

During her career Brown has taught English at Dartmouth College while leading a range of reading and discussion programs for adults, including National Endowment for the Humanities programs for medical and military professionals. She edited the anthology Echoes of War, used as a reader for health care professionals at Veterans Administration Healthcare Centers. Currently she works with the Vermont Humanities Council, facilitating discussions of literature for female veterans.

Recently we asked Brown how literature deepens our understanding of Americans’ war experience.

Primary documents recorded Americans’ World War experience as it happened. Imaginative writers recollected this experience in fiction and poetry. Does literature give us a distanced perspective on history?

I actually don’t find historical and literary documents to differ in that way. A lot of the poems on the syllabus were written during a war; and some primary documents, like Harding’s Address at the Burial of an Unknown American Soldier, were written after a war ended. Teaching primary documents along with literature pushes me to think not only about the “time setting” of the action in a fictional story, but also the time of composition and the time of publication. For example, Willa Cather wrote One of Ours as Americans were trying to understand what their participation in World War I meant. Memorials were going up all across the country. Americans had arrived on the battlefield late in the war but in time for some of the hardest fighting. Enough time had passed for them to question whether this war had indeed, as President Wilson claimed, made “the world safe for democracy.” You need to read the primary documents of the 1920s to understand this.

What most distinguishes the imaginative accounts from the primary documents is their diction. Imaginative writers strive for honest, concrete language. When they challenge the politicians’ accounts, it may be not the judgments but the rhetoric of public figures they most object to. Yet how may a leader remind people of what they are sacrificing, fighting, and dying for without creating a cloud of abstraction that diminishes the specific horror of that sacrifice? The Gettysburg Address is the best solution to that problem I know of, and I think its very brevity enables its success.

In the case of Hemingway, I suspect his famously terse prose style in part reflects his suspicion that talking about war experience somehow distorts or sullies it.

Cather and Hemingway offer contrasting accounts of World War I. Hemingway served during the war, while Cather only read and thought about it. Does this explain their different perspectives?

Hemingway accused Cather of learning about combat from the movie The Birth of a Nation, adding, “Poor woman, she had to get her war experience somewhere.” In fact, Cather spent several months in 1918 interviewing veterans of the war and reading letters they sent home from the front, most carefully those sent home by her cousin G. P Cather, whose death in action at Cantigny was the real impetus for the book.

One of Ours was often misread as a book that sentimentalized and romanticized death in war, until the 1980s, when Cather scholars challenged this reading. I suspect Hemingway, jealously defending his own war experience, and jealous of Cather’s 1923 Pulitzer Prize, misread the novel.

Interestingly, Cather said she feared the book would be read as a war story. It was the character of her cousin that fascinated her: a misfit on the prairie farm, someone who goes to war in search of a worthy purpose. Cather portrays Claude’s romantic idealism in a complex way. We’ll have a lot to discuss as we consider whether Cather sees this idealism as a positive or negative thing.

Was idealism always a motive for enlistment? What about those marginalized at home due to their race or ethnic origins?

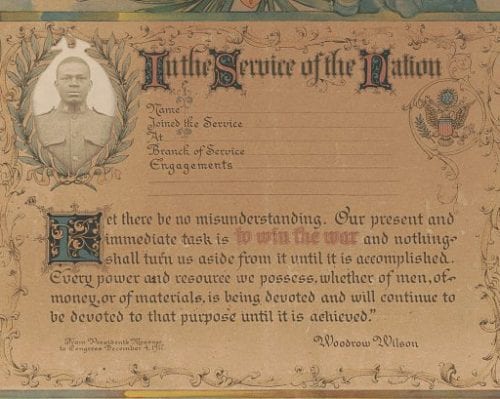

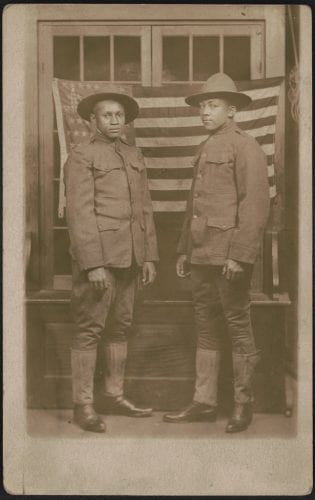

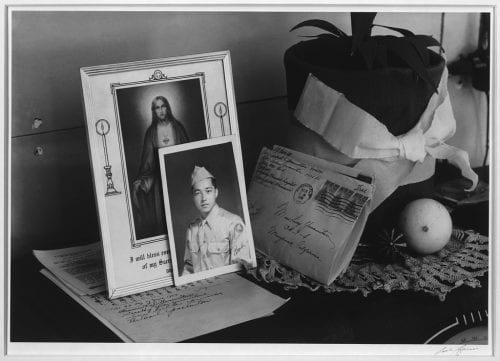

Of course, many Americans were drafted before they volunteered. David Laskin in The Long Way Home writes about Southern and Eastern European immigrants to this country who were sent off to war very soon after their arrival. He concludes that the war helped them assimilate and embrace their American identity. The rude epithets used against them at home by Anglo Americans were also used within their units, but as affectionate terms. African Americans had a mixed experience. They hoped their service would push the nation to recognize and honor their rights, and sometimes, while serving, they experienced advancement. At other times, military policy reinforced segregation. The welcome that many black service members were given in France during World War I contrasted painfully with their treatment by the US military and with segregation at home. Still, we see writers like Marilyn Nelson, whose father was a Tuskegee airman in WWII, expressing great pride in African Americans’ service. German American civilians faced hostility from their neighbors during World War I, as Japanese Americans did during World War II, yet writers like Cather and the photo journalist Ansel Adams highlight the patriotic service of soldiers who share an ethnic connection with the enemy.

Veterans often avoid speaking of their war experience. Why should civilians read about that experience?

Veterans keep silence for many reasons—because they don’t want to shock civilians, because they doubt civilians can understand what they did, because the memories are painful, or perhaps because they need to protect a space in their lives that has nothing to do with the war. Yet we need to know about their experience. As citizens, we elect and deputize representatives who decide when and where we send soldiers to fight; we need to know what this service costs those soldiers. As neighbors, parents, siblings, and children of those who have fought, we need the information to support those we love. At the VA hospital, many health care providers have told me about veterans of World War II who, under the influence of drugs or dementia, return to their days as soldiers and relive aspects of the war they have never before talked about. Increasingly, military and health professionals understand that we need to prepare soldiers for a return to civilian life as thoroughly and thoughtfully as we prepare them to become warriors. To support this, we should help civilians understand the challenges returning soldiers face.

Learn more about this summer’s history and literature seminars.