America and the World - A Never Ending Debate

If you are old enough, say thirty or older, you remember where you were and what you were doing when you heard. You remember who told you. You recall the look of shock, anger, or dismay in their eyes. I was in my home office, confirming business appointments scheduled for later that week. My mother-in-law called my wife, Linda, and asked if we knew two planes had struck the World Trade Center towers in New York. Like millions of other Americans—not just those in New York or Washington—we shut our work down for the day. We sat glued to our TV, hoping the news was not as bad as we feared and wondering what was coming next.

The President of the United States was with students in a Florida classroom when he was told of the attacks. He was listening to them read a story from a book published by SRA/McGraw-Hill, my employer at the time. The president of SRA, Peter Sayeski, was in New York on his way to a meeting at McGraw-Hill headquarters near the World Trade Center. Months later, Pete told me that when the first plane struck the North Tower and traffic in Manhattan came to a halt, he and his cab driver got out of the car, just in time to see the second plane hit the South Tower.

“What did you do then?” I asked Pete.

“I looked up,” he said, mimicking his search skyward as he told his story. “I didn’t know how many more there were – one? Four? Ten? A hundred?”

Pete’s story captures the uncertainty that many Americans felt that day. The oceans no longer protected us. A new enemy arrived—one not carrying declarations of war or wearing recognizable uniforms. They employed a new tactic—one not seen before on American soil – the use of commercial aircraft as a weapon of war. They, attacked covertly, using our freedoms against us. The nature of modern warfare seemed to change forever in a single day. No longer were the old ways of thinking about homeland security valid. To guard against future attacks, the very freedom we valued might need to be restricted.

Throughout its history, US defense strategy had been predicated, in part, on our geographic isolation. Tension existed between our values as expressed in the Declaration of Independence and our national interests. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams attempted to bridge this divide when he argued in 1824 that “Wherever the standard of freedom and Independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her [the United States’] heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” Now a monster had come to our shores, striking our cities, financial institutions, and military headquarters. Only the actions of the brave passengers of Flight 93 that day prevented more damage.

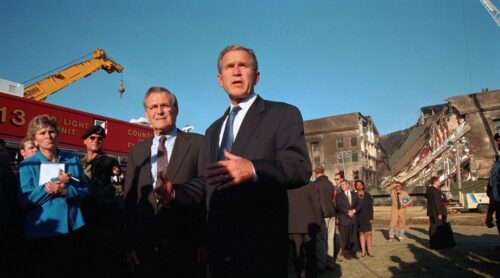

There was little debate among Americans regarding the proper response to the attacks of 9/11. The Bush Administration identified al Qaeda, led by Osama bin Laden, as the perpetrators. Bush demanded that the government of Afghanistan, known as the Taliban, hand over bin Laden. When the Taliban refused, Bush ordered an invasion of Afghanistan with the stated intention of finding and bringing to justice all those responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Bush left office before the US killed bin Laden. In 2011, President Obama ordered a nighttime raid on the terrorist leader’s hideout that resulted in his death. As time passed, mission creep set in and the US practiced nation building in Afghanistan though policy makers were reluctant to use that term. Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump pledged to end US involvement in the Afghan War but were unable to fulfill that promise prior to leaving office.

As I write this post, United States military personnel are withdrawing from Afghanistan after 20 years of war and ten years after the killing of Osama bin Laden—the original goal of the Afghan invasion. The Taliban—the people who protected the 9/11 hijackers—have retaken control of Afghanistan. The question now: “Will all Americans and the Afghans who risked their lives to help them get out?” Scenes from the Kabul airport are gut-wrenching, and once again, uncertainty reigns.

Throughout our history, Americans have debated whether our foreign policy should be guided by our core political values or by our national interest. Perhaps the only certain outcome of this debate is that it will continue. Should we remain a nation seeking to avoid permanent alliances with all others, as George Washington argued in his Farewell Address? Or was President George W. Bush correct when he argued that “The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world”? If Bush was correct, does America have a proactive duty to expand freedom around the world?

For the last fifteen months, this blog has featured two posts per month about our two-volume Core Document Collection, Documents and Debates in American History and Government. Today, we reach the end of this project with Chapter 29 of Volume Two, America and the World. Just as he did for the previous 28 chapters, our colleague Jeremy Gypton has recorded the documents in the chapter. We hope the recordings Jeremy painstakingly made prove beneficial to second language learners or students with reading challenges. All the chapters and the recorded documents are available on our website.

The documents in this chapter include:

A. President George W. Bush, Inaugural Address, January 20, 2005

B. President Barack Obama, Address at Cairo University, June 4, 2009

C. Senator Rand Paul, “Containment and Radical Islam,” February 6, 2013

Students of the post-9/11 world are coming of age as the US enters a new phase of international relations. The Cold War is over; the Soviet Union is dismantled but US-Russian relations remain fraught with peril. Asia, especially China, exerts an increasing financial and military presence. Radical Islam is constantly shifting, making its next offensive challenging to predict. American technology and economic dominance continue to “shrink the world” and cause consternation among those living in traditional societies. What an exciting time to teach! As teachers of American history we have the opportunity to challenge students to think carefully about these issues that will impact the rest of their lives. The documents in this chapter and others linked below will help teachers challenge students to think about the fundamental challenge to a republic like America. Should we focus on American interests or American values? The debate continues.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

George Washington’s Farewell Address, September 19, 1796

The Helvidius-Pacificus Debate on Neutrality Proclamation, 1793

John Quincy Adams, An Address Celebrating the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1821

Henry Clay, Speech on the Mexican-American War, 1847

Platform of the American Anti-Imperialist League, 1899

Albert J Beveridge, In Support of an American Empire, January 9, 1900

John F. Kennedy, Inaugural Address, January 20, 1961

Ronald Reagan, Remarks on East-West Relations at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin, June 12, 1987