Marbury v. Madison: The Origins of Judicial Review?

Today marks the 219th anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court case, Marbury v. Madison.

The Midnight Judges

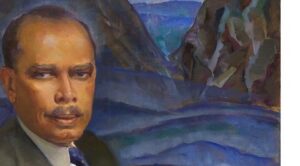

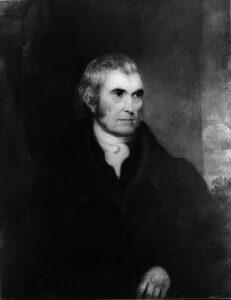

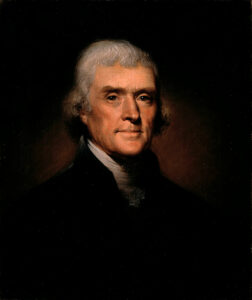

In the waning days of the Adams Administration in early 1801, the Federalist Congress tried to strengthen the federal judiciary and soften its defeat in the election of 1800 by creating a number of federal judgeships, including justice of the peace positions in Washington DC. President Adams signed one of those justice of the peace commissions for William Marbury. However, the commission did not make it from Secretary of State John Marshall to Marbury before the new Jefferson Administration took over in March 1801. In the meantime, Marshall had been confirmed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

When the new Administration took office, Secretary of State James Madison refused to give Marbury his commission. Marbury thereupon sued Madison and asked the Supreme Court to issue Madison a writ of mandamus, a judicial order requiring Madison to hand over the commission. The Court had been given the power to issue such writs in Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789.

Judicial Review

Eventually, the Supreme Court took Marbury’s case, and in 1803 it handed down what has been widely viewed as one of its most important decisions. Many people believe that Marshall’s opinion established the practice of judicial review— the power of the federal courts to strike down unconstitutional laws and executive actions. Others go further and contend that Marbury declared the Supreme Court to be the final, authoritative interpreter of the Constitution. Neither is true. As one scholar has noted, the Supreme Court had already been practicing judicial review before Marshall arrived: from 1789-1801, it decided eight cases involving a constitutional challenge to federal laws and did the same in at least three cases involving state laws. While President Thomas Jefferson did not like the part of Marshall’s opinion declaring that Marbury had a right to receive his commission from Madison, Jefferson did not object to the opinion’s argument that the Supreme Court could declare an act of Congress unconstitutional and therefore void.

Perhaps that is because Marshall did not declare the Court supreme over the other branches in its interpretation of the Constitution. In Marshall’s view, declaring a law “void” simply meant that it did not operate in a federal court; so in this case, the Supreme Court could not follow Section 13, which Marshall interpreted as unconstitutionally giving the Court original jurisdiction to issue a writ of mandamus to executive officials like Madison. Marshall did not say that the Court’s constitutional interpretation bound the other branches; he simply denied that the other branches’ interpretation bound the Court. It had the power to interpret the Supreme Law of the land for itself in order to decide the legal case in front of it.

The Importance of Marbury v. Madison

So why then was Marbury so important? It established the Supreme Court as a politically and constitutionally independent branch of the federal government, which was by no means clear in the early days of the Republic. In 1803, the Supreme Court was a weak institution facing great political pressure from the High Federalists on one side (who wanted the Court to assert its authority and embarrass Jefferson politically by forcing him to give Marbury his commission) and the victorious Republicans on the other side (who wanted Jefferson to refuse to comply and thus weaken the federal judiciary in favor of state courts). Marshall skillfully avoided both extremes: he pleased the Federalists by declaring that Madison owed Marbury his commission, but he avoided an unwinnable confrontation with Jefferson by saying that the Court could not legally issue the order to Madison. Instead of using the case to establish the practice of judicial review, Marshall articulated the doctrine of judicial review to decide the case in a way that protected and strengthened the independence of the federal judiciary, which he believed to be essential for a national republic governed by the rule of law and respect for the rights of individuals.