Containment and the Truman Doctrine: Documents and Debates

Like many youngsters interested in history, I read only books about presidents and generals as a boy. Harry Truman became my favorite president—in part because my grandmother claimed to be the only person in America, other than Truman himself, who believed Harry would win in 1948—in part because of a near miss chance to talk with him in 1968. I knew a lot about Harry before starting college. Still, I lacked an appreciation of the career officials’ role in the formulation of foreign policy—those highly educated men and women, devoted to public service and dedicated to life-long study of significant issues facing the nation and the world, advising the elected leaders from inside the State Department. I learned a lot about the bureaucracy in my undergraduate political science classes. Still, one book that I read long after my college days—The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made, by Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas, illuminated this side of government more than any other book I ever read.

Isaacson and Thomas describe how six diplomats, working closely with then-Secretary of State George Marshall and President Harry Truman, formulated United States foreign policy in the early Cold War era. These six men—Dean Acheson, W. Averill Harriman, George Kennan, Charles E Bohlen, Robert Lovett, and John McCloy—shaped the post-war world. These six men, plus Secretary Marshall, formed what may be the finest foreign policy team in American history. While crafting U.S. policy toward communism, they created economic and political institutions that shifted U.S. foreign policy toward international cooperation—abandoning America’s historical isolationism. Perhaps the best known of the six “Wise Men” are W. Averill Harriman, a descendent of the Harriman railroad tycoon and later governor of New York, and Dean Acheson, who replaced Marshall as Secretary of State in 1950. The man who fascinated me the most, however, was George F. Kennan.

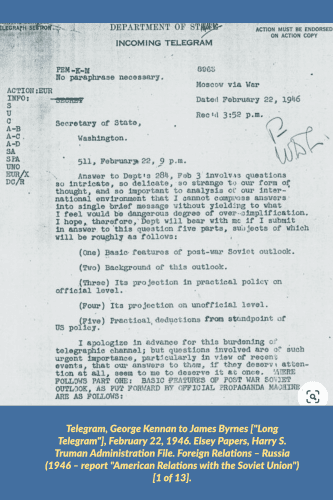

Kennan, a U.S. diplomat, was fluent in the Russian language, knowledgeable of Russian history and culture, and perceptive about the similarities and differences between tsarist Russia and Stalinist Russia. Stationed in Moscow as U.S Chargé, Kennan responded to a 1946 State Department request with a lengthy analysis of Soviet perceptions of the capitalist world. He predicted the likely Soviet initiatives predicated upon those perceptions. Kennan’s response became known as the “Long Telegram,” and it formed the basis for the bipartisan U.S. policy of containment—a policy embraced by nine presidents and enduring to the end of the Cold War in 1989.

Containment, although conceptually simple, proved complex in its implementation. It called for U.S. policy initiatives toward communism in general, and the Soviet Union specifically, to “contain” communism in countries where it existed in 1946. Thus, the Marshall Plan’s purpose was in part a humanitarian effort to rebuild the European economy, in part an effort to prevent starving Europeans from embracing communist parties in their country. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) posed a military deterrent to a potential Russian assault on Western Europe. Combined, the Marshall Plan and NATO prevented communism from gaining ground in Western Europe.

Kennan used the word containment for the first time in July of 1947 when he published his thoughts in Foreign Affairs magazine under the pseudonym “Mr. X.” He argued that “The main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.” (emphasis mine). Kennan believed patient containment might lead to a collapse of the Soviet system. Most Eastern Europeans were not ideologically disposed toward Marxism and had no loyalty to Russia. Therefore, Kennan foresaw the Soviet regime strained with burdens not unlike those of the old tsarist regimes. He doubted the Soviet system would establish orderly transitions from one leader to the next. Each time leadership passed to a new generation of leaders, the system would pass through an era of instability it might not survive.

Containment policy was first applied in March of 1947, after Great Britain notified the Truman administration that they were no longer able to financially and militarily support Greece and Turkey. In an address to Congress now known as the Truman Doctrine, Truman said the world, fresh from its triumph over fascism, faced a new rivalry between democracy and despotism. Truman expressed his belief that “it must be the policy of the United States to support free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” (Document C) Though Truman emphasized that American aid would be primarily financial and economic, his apparently open-ended commitment to support “free peoples” anywhere in the world seemed to risk military intervention in remote countries. This was a risk identified by critics of containment such as Walter Lippmann, who argued that containment might force “us to expend our energies and our substance upon . . . dubious and unnatural allies.” (Document B)

Containment had other critics from the beginning—notably former Vice-President Henry Wallace (Document D). The criticism increased as the Cold War rivals competed for ideological beachheads in developing countries. Eventually, Kennan himself became a critic of containment policy. He regretted the militarization of his policies—what he saw as the misapplication of containment in Vietnam. In 1966, in testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Kennan opposed unilateral withdrawal from Vietnam, but stated unequivocally that if the U.S. was not already involved, he knew “of no reason why we (U.S.) should become involved and . . . several reasons why we should not wish to.”

Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger notes in his book, Diplomacy, that Kennan’s “Long Telegram” became “One of those rare embassy reports that would by itself reshape Washington’s view of the world.” Still, as Kissinger notes, Washington failed to appreciate the nuance in Kennan’s argument—that “Soviet foreign policy was an amalgam of communist ideological zeal and old-fashioned tsarist expansionism.” Kennan was an expert on Russia—Russian history, Russian culture, Russian politics. His suggestions were designed to combat “Russian expansive tendencies,” not those of other nations. Kennan argued that the Kremlin’s “neurotic view of world affairs” was based on the combination of a “traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity” and communist belief that the world was not big enough for both communism and capitalism. One would ultimately prevail over the other.

Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger notes in his book, Diplomacy, that Kennan’s “Long Telegram” became “One of those rare embassy reports that would by itself reshape Washington’s view of the world.” Still, as Kissinger notes, Washington failed to appreciate the nuance in Kennan’s argument—that “Soviet foreign policy was an amalgam of communist ideological zeal and old-fashioned tsarist expansionism.” Kennan was an expert on Russia—Russian history, Russian culture, Russian politics. His suggestions were designed to combat “Russian expansive tendencies,” not those of other nations. Kennan argued that the Kremlin’s “neurotic view of world affairs” was based on the combination of a “traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity” and communist belief that the world was not big enough for both communism and capitalism. One would ultimately prevail over the other.

Containment became the framework of U.S. foreign policy beyond its initial Euro-centric focus on Russia. Yet its application in Asia, Africa, and Latin America raises interesting questions for students of American history. If the policy was meant to apply only to Russian communism, how should the U.S. have responded to other communist nations? If communism was a monolithic movement bent on world domination and controlled by the Kremlin’s puppet masters, as most Americans believed, should containment policy have been expanded to other areas of the world? What criteria might the U.S. use to determine whether a given country might be in the vital interest of the U.S., making military intervention necessary to block a communist take-over there?

A careful study of the documents in Chapter 24: Containment and the Truman Doctrine should help students of the era propose their own answers to these questions. The documents also raise two more important questions: Were the problems of containment foreseeable in 1946 and if so, why were they ignored?—and, Can we forgive the misuse of containment, because it was ultimately successful? The USSR and the U.S. never engaged in direct conflict. The USSR collapsed in 1989, in much the same way as Kennan had predicted in 1946.

Documents in this chapter include:

A. George F. Kennan to the Secretary of State, February 22, 1946

B. Walter Lippmann, The Cold War, 1947

C. President Harry Truman, Address of the President of the United States (Truman Doctrine), March 12, 1947

D. Henry Wallace, Critique of the Truman Doctrine, March 13, 1947

We have also provided audio recordings of the chapter’s Introduction, Documents, and Study Questions. You’ll find these just beneath the headings for each element of the chapter. These recordings support literacy development for struggling readers and the comprehension of challenging text for all students.

Teaching American History: We the Teachers blog will feature chapters from our two-volume Documents and Debates in American History with their accompanying audio recordings each month until recordings of all 29 chapters are complete. Following today’s post on Volume II, Chapter 24, we turn, on April 13, to Volume I, Chapter 11: The Nullification Crisis. We invite you to continue following this blog closely, so you will be able to take advantage of the new audio feature as the recordings become available.