The Origins of Memorial Day

This post originally ran on May 23, 2019

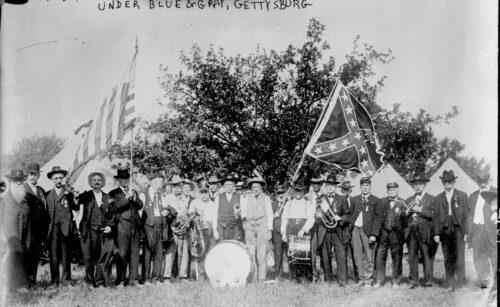

Did you know that the origins of Memorial Day and its remembrance of America’s servicemen and women arose in response to the divisions left by the Civil War? On the Religion In America website, Ellen Tucker explains that the North celebrated “Decoration Day” in late May to honor the sacrifices of those who fought for the Union, while the South observed a separate memorial day in late April. Yet an early gesture of reconciliation would lay the groundwork for the decision, after World War I, to observe a single, national day honoring the fallen of all American wars.

According to Tucker, a news story about how a group of Southern women honored the graves of dead Union soldiers in a cemetery in Columbus, Mississippi on April 25, 1866–less than a year after the end of the Civil War–inspired poet Francis Miles Finch to write the poem “The Blue and the Gray.”

By the flow of the inland river

Whence the fleets of iron have fled,

Where the blades of the grave-grass quiver,

Asleep are the ranks of the dead:—

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the Judgment Day:—

Under the one, the Blue;

Under the other, the Gray.

These in the robings of glory,

Those in the gloom of defeat,

All with the battle-blood gory,

In the dusk of eternity meet:—

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the Judgment Day:—

Under the laurel, the Blue;

Under the willow, the Gray.

Tucker says the poem “paints a non-judgmental image of the dead of both sides: sleeping in a single cemetery while awaiting God’s ultimate judgment.” Yet Finch (and the Southern women who inspired him) sounded a theme that would not be widely embraced until the end of the century. In the decades prior, North and South used these commemorations of the fallen to emphasize their distinct views of the war’s motives. Speakers at Northern memorial events emphasized the moral imperatives behind the war–freedom, union, and the principle of majority rule; in the South, memorial events contributed to the construction and maintenance of the “Lost Cause” mentality. These distinct moral positions would fade in popular memory by the time the nation mourned its losses in World War I.