Echoes from Dealey Plaza

On this day, 59 years ago, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, TX. The following blog post is an excerpt from MAHG faculty member Stephen Knott’s book, Coming to Terms with John F. Kennedy.

The birth of modern America’s obsession with conspiracy theories began at approximately 12:30 p.m. central standard time on November 22, 1963. Long before Donald Trump’s presidency, an omnipotent “Deep State” was accused of being the perpetrator of one of the greatest crimes of the twentieth century. Trump himself would contribute to the endless proliferation of unsupported theories about Kennedy’s killing, suggesting that the father of Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) was one of Kennedy’s murderers.

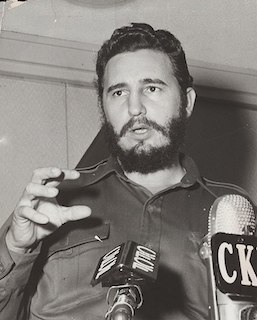

The Warren Commission’s conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone was accepted by 87 percent of Americans when the report was released on November 23, 1964. But decades of microscopic parsing of the commission’s report, aided and abetted by the American government’s effort to conceal Operation Mongoose, the codename for the CIA’s covert campaign to topple Fidel Castro’s government that included assassination plots, led to a complete turnaround in public support for the idea that a lone gunman killed Kennedy. On the fiftieth anniversary of Kennedy’s murder in 2013, nearly two-thirds of the American public believed that Oswald was part of a broad conspiracy.

The tragic event in Dallas would elevate conspiracy theories on the left to something akin to a secular gospel. This development has been remarkably destructive, as it represents an abandonment of what Kennedy himself was scheduled to say at the Dallas Trade Mart on November 22, 1963. In his prepared remarks, the president noted that America must be “guided by the lights of learning and reason.” And, he added, “but today other voices are heard in the land—voices preaching doctrines wholly unrelated to reality; we can hope that fewer people will listen to nonsense.”

Any objective account of the assassination of President Kennedy must acknowledge the animus toward Kennedy from the mob, from the anti-Castro Cuban community, from Fidel Castro, and from right-wing elements in Dallas, not to mention the failures of the Secret Service. But if one can move beyond ideological predispositions and the desire to make use of the murder victim as a martyr for a great cause, then all the evidence points to Lee Harvey Oswald as President Kennedy’s lone assassin. The evidence against Oswald is overwhelming, yet despite this the Kennedy assassination will likely remain an “unsolved” mystery in the minds of most Americans.

The main counts in the indictment against Lee Harvey Oswald include the following: After returning from Russia in 1962, he created secret identities for himself, and ordered a rifle under an assumed name, A. Hidell, that he would use to shoot at both retired General Edwin Walker and President Kennedy. Oswald staked out General Walker’s house and included photos of the home in his “book of operations.” Oswald attempted to assassinate Walker on April 10, 1963, and having failed to kill Walker, he latched on to a new cause—defending Castro from American sponsored assaults on Cuba.

Oswald hoped to add a dramatic entry to his self-proclaimed “Historic Diary” that he kept for a time, dreaming about leaving a mark on the Cold War struggle between Marxism and capitalism. Inscribed on the back of a photograph taken by Marina Oswald in April 1963 of Lee holding the rifle that killed President Kennedy were the words “Hunter of Fascists,” written in Russian. Throughout the last year of his life, Oswald was determined to travel to Cuba and meet with Cuban officials and impress them with his actions in defense of their regime.

On the morning of Friday, November 22, 1963, Oswald brought a package of “curtain rods” into the Texas School Book Depository, and immediately after the shooting, his rifle, with his palm print, was found on the sixth floor of the building. One eyewitness in Dealey Plaza, fifteen-year-old Amos Lee Euins, tried to convince Dallas Police to direct their attention to the book depository rather than the grassy knoll, for he saw a man firing a rifle from the sixth floor of that building. Even the House Select Committee on Assassinations, no friend of the Warren Commission, concluded that “the shots that struck President Kennedy from behind him were fired from the sixth floor window of the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository building,” although they conjectured based on faulty acoustics evidence that there may have been another gunman firing from the grassy knoll.

Additionally, the House Committee noted that a number of the Dealey Plaza witnesses, in addition to Amos Lee Euins, said they saw either a rifle or a man with a rifle in the vicinity of the sixth floor southeast corner window. Three employees watching the motorcade from the fifth floor of the building testified that the shots were fired from above them; one of the men yelled, “It’s coming right over our heads,” while another recalled the sound of shell casings hitting the floor, and “three shots” so loud they shook the building; “Cement even fell on my head,” one of the men stated. Several eyewitnesses saw Oswald, the only depository employee to flee the building after the assassination, shoot Dallas Police Officer J. D. Tippit.

The bottom line regarding the Kennedy assassination is that there was a cover-up, and it was designed to conceal the existence of Operation Mongoose. This distorted the Warren Commission’s report to the nation, but they got it right when it came to who killed the president. For Lee Harvey Oswald, “fair play for Cuba” meant, as one scholar of the assassination observed, “subjecting [President] Kennedy to the same dangers plaguing Castro.”

Despite the overwhelming evidence that Lee Harvey Oswald killed the president, the Kennedy assassination conspiracy complex continues to flourish. Priscilla Johnson McMillan, the only person who knew both President Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald and concluded that the latter was the assassin, noted in 1975 that “the killing of a President, or a king or father, is the hardest of all crimes for men to deal with; it is this crime that stirs the deepest guilt and anxiety. No matter what steps are taken, what investigation may be authorized or what autopsy material made public, I suspect that the doubts about President Kennedy’s murder are going to be with us forever.”