Executive Order 8802: 80 Years Later

This June 25 marks the 80th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802, prohibiting discrimination in the defense industry. Considered from three critical perspectives, this small but important step in America’s uneasy movement toward greater freedom and equality provides successively deepening lessons to history students probing the significance of Roosevelt’s order.

The first perspective uses primary sources to understand Roosevelt’s motivations in his own words. In this case, it’s helpful to read Executive Order 8802 alongside Roosevelt’s January 1941 Annual Message to Congress (“The Four Freedoms”). 8802 was a logical extension of Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech that committed America to supplying the “arsenal of democracy” for the Allied war effort (the United States would not directly join the military conflict until December). That address framed the overseas war as an essential defense of “the democratic way of life” and “democratic existence” — highlighting democracy as a social principle and manifestation of freedom. This framing aligned core American values with the war effort, justifying the tremendous increase in industrial productivity Roosevelt demanded. It also demanded a reflective look at situations within America’s borders where social democracy was compromised, undermined, or thwarted. Here, the lived experience of African Americans attested to the limits of freedom, most notably (though not exclusively) in the Jim Crow South. African Americans’ most common employment came through agricultural and domestic work, which was why Southern Democrats had made certain that those labor categories were excluded from New Deal programs like Social Security.

The certain boom in home front industrial labor from 8802 would offer a new employment avenue — one that would not be subject to this “Southern Veto.” The central directive of Executive Order 8802 decrees that “there shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origin.” In 8802, Roosevelt justified this stance with a logical deduction. First, Roosevelt encouraged “full participation in the national defense program by all citizens … [because] the democratic way of life within the Nation can be defended successfully only with the help and support of all groups within its borders.” Combine this assertion with the ground-level reality that employment discrimination led to “workers [being] barred from employment in [defense] industries … to the detriment of workers’ morale and of national unity,” and Roosevelt’s executive order comes across as the timely action that American freedom required.

While Roosevelt’s own words provide insight into 8802, they only tell part of the story, and indeed, our president-centric media culture — where presidents are often cast as singular visionary deciders — might encourage such a limited historical view. The unitary force of executive orders contributes to this as well — and FDR was, more than any other, the “executive order president,” signing both the greatest number and highest rate of such directives. So students could be forgiven for thinking of presidents as historical actors in a vacuum, with executive orders like 8802 taking on the flavor of royal decree. But in a democratic system presidents respond to pressure and incentive almost as often as they wield it. Here contextual scrutiny offers another perspective that complicates and enriches this story. Changing circumstances led Roosevelt to advance an agenda from which he had previously remained aloof. While aspects of the New Deal had helped African Americans (and brought Black voters in Great Migration cities into Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition), Roosevelt had maintained careful distance from civil rights matters and rebuffed repeated entreaties throughout the 1930s from organizations like the NAACP and Urban League to ensure a more inclusive democratic society. Certainly this had been in part a political calculation: Roosevelt depended on the support of those aforementioned Southern Democrats to advance the New Deal agenda, and they were actively hostile to any challenge to the racial status quo.

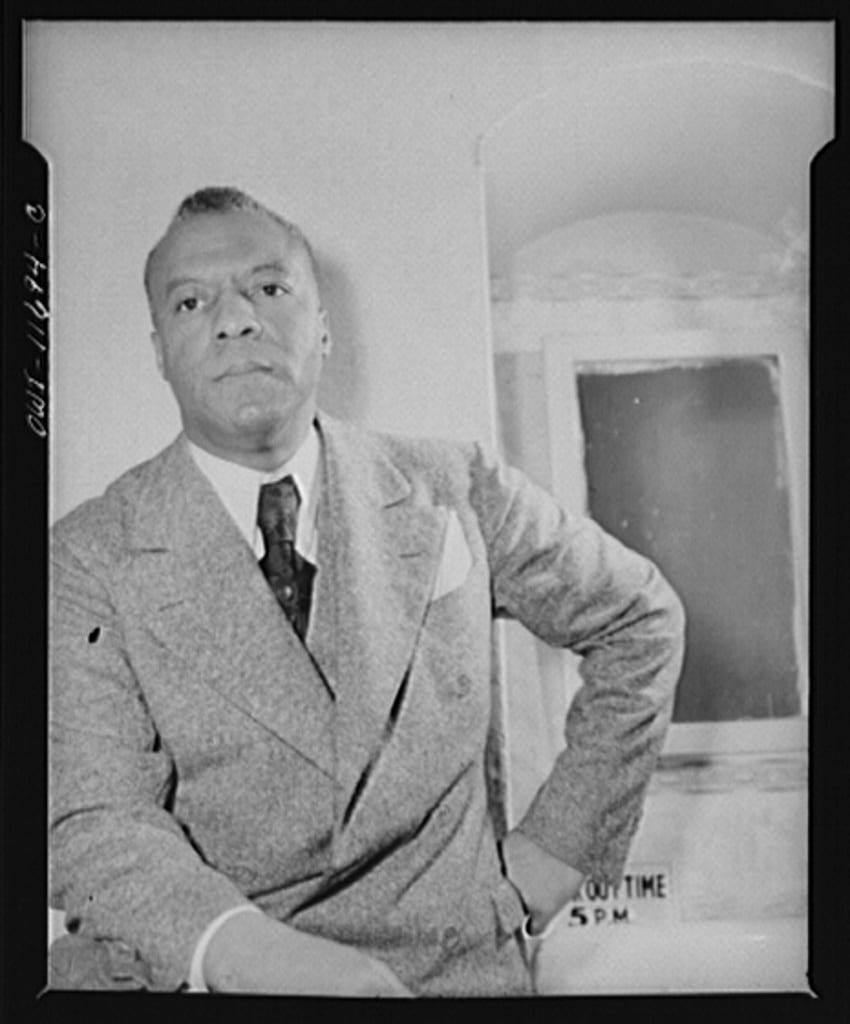

And yet changes in circumstance made Executive Order 8802 possible by June 1941. As noted above, Roosevelt acknowledges one crucial change himself — World War II. Promoting the global cause of freedom shined a harsh light on freedom’s boundaries at home. But there was far more direct pressure on Roosevelt, pointedly in the form of a threatened protest march. Enter A. Philip Randolph, civil rights activist and President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (the first African American union recognized by the AFL), whose writings in 1941 reveal a successful advocacy campaign. Rallying an African American audience in May 1941, Randolph published “The Call to Negro America to March on Washington” in Black Worker, imploring African Americans to use their “mass power [to] cause PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT TO ISSUE AN EXECUTIVE ORDER ABOLISHING DISCRIMINATIONS IN ALL … NATIONAL DEFENSE JOBS.” Referencing African Americans’ established record of “courage, determination, and will to struggle,” Randolph insisted that American democracy “defend its defenders … protect its protectors” and “insure equality of opportunity, freedom, and justice to its citizens.” While President Roosevelt is a peripheral audience for this appeal, Randolph sent a more direct appeal in a June 16, 1941 letter to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, attaching the March-on-Washington committee’s six-point proposal for desegregating home front defense work and enclosing information about march preparations for the president’s consideration. While this proposal was far more detailed than the final executive order, most particulars of 8802 can be found in the March-on-Washington Committee’s proposal. Providing students with these primary documents allows them to connect social history to political history and draw a direct line from citizen action to government action.

Finally, we can zoom out from close readings of 1941 documents and consider 8802 in a broader historical perspective. Considered on a longer timeline there’s a case to be made for considering 8802 the launching point of the Civil Rights Movement. Certainly African Americans have advocated for their rights throughout American history. But if we periodize the Civil Rights Movement as something with a distinct shape, what sets it apart? If we consider the movement as a “Second Reconstruction,” then we must note that 8802 established the Fair Employment Practices Commission — the first federal agency since Reconstruction established to investigate acts of anti-black discrimination. If we consider it further as (in legal scholar Sherrilyn Ifill’s terms) “The People’s Reconstruction,” an era defined foremost by citizen action, then the March-on-Washington Committee’s successful advocacy, reflected in the final order, corroborates this claim as well. Later in the Civil Rights Movement A. Philip Randolph successfully advocated for the desegregation of the military (EO9981, 1948) and helped organize the Civil Rights Movement’s most celebrated event, 1963’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Indeed, the full title of the 1963 march traces back to the earlier proposed march: the 1941 March-on-Washington committee’s informational pamphlet refers to their intended event as a “NEGRO MARCH for JOBS and JUSTICE.” These formal titles remind us that concepts like “freedom” and “justice” are abstract until given practical, concrete form. What opportunities does freedom afford? What access does it grant? These are questions for which the Civil Rights Movement demanded answers, and we can trace a line of successful petitions (through the 1960s) beginning in the citizen action of 8802.

I started this post by referring to 8802 as small-but-important, and I’d like to return and close there. 8802 ensured that WW2 home front boomtowns would be diverse boomtowns as well, and buoyed the second Great Migration, a movement of African Americans to industrial centers even larger than the better-known first (or early) Great Migration. However, this did not make them integrated boomtowns. Workers of color in the defense industry often faced segregation in the workforce as they did in the military, as well as prejudice and hostility from white workers and residents in these boomtowns. And the path to greater equality and inclusion did not always move consistently forward, as 1942’s Executive Order 9066, directing Japanese internment, clearly attests. So the ultimate impact of 8802 may be considered modest in comparative scale to its advocates’ goals, the larger social movement, and the work to be done. But 8802 established federal re-engagement in matters of race and equality, a crucial commitment to America’s promise. And its larger context is a testament to the power of citizen action. In both of these regards, it remains an important and underappreciated event, signposting a path for positive change.

Additional Works Consulted

Gilford, Steve. Build ‘Em by the Mile, Cut ‘Em off by the Yard: How Henry J. Kaiser and the Rosies Helped Win World War II. Richmond, CA: Richmond Museum Association, 2011.

Kennedy, David M. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford UP, 1999.

Lepore, Jill. These Truths: A History of the United States. New York: W.W. Norton, 2018.

National Constitution Center. “What Constitutes a ‘Reconstruction’, and Could it Happen Today?” YouTube. Uploaded 4 May 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmVJZqHguyg

Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park. Rosie the Riveter Trust/National Park Service, 2020.