For Constitution Day: The Road toward the 13th Amendment, begun at Antietam

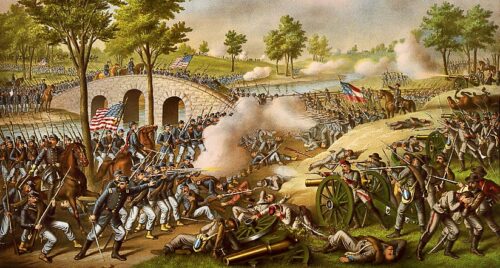

In July we noted the remarkable coincidence of major events in American history falling on Independence Day. Another striking coincidence involves Constitution Day. On September 17, 1787, delegates to the Constitutional Convention signed the document they’d created during weeks of tense debate and deliberation, a document that, in amended form, still serves as our framework of government. Seventy-five years later to the day, American soldiers suffered the bloodiest single day of combat in our nation’s entire history: the Battle of Antietam.

To me, this seems more than a melancholy coincidence. In our current moment, when the founders are routinely castigated for allowing concessions to slaveholders to mar their original plan of government, remembering Antietam may prompt us to think through the challenging task Americans faced as they revised the founders’ work. The costly Union victory at Antietam marked the beginning of this revision. It gave President Abraham Lincoln the military victory he needed to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Changing his war strategy in this way, Lincoln changed the public understanding of the Civil War’s purpose. He also announced an intention that led to passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Timing the Proclamation

Lincoln had been mulling over an emancipation proclamation for months before he showed a preliminary draft to his cabinet on July 22, 1862. Although he abhorred slavery, Lincoln did not think the Constitution permitted him to act unilaterally to end it—unless, as commander in chief, he could do so as a military necessity. He was well aware of the military advantage slave labor brought the Confederates. Enslaved people were used to construct military defenses, dig latrines, transport supplies, cook, and launder for the rebel troops; they also continued working (under overseers) on southern plantations, so that southern men could fight without leaving civilians unprovided for. Depriving the South of this free labor force would seriously weaken it. An emancipation proclamation would also rebuff the frequent demands of Northern “Copperhead” Democrats that Lincoln negotiate for peace. It would underscore the Lincoln administration’s determination to prevent the emergence of an independent slaveholding nation in the South.

In a limited way, emancipation had been underway for months, due to the actions of enslaved people who ran away to Union lines as the army made its way into the south. Many Union commanders began feeding and sheltering the runaways, putting them to work performing support services similar to those the Confederates had required them to perform. To clarify expectations for how runaways would be treated and employed by the Union army, Congress had already passed the first and second Confiscation Acts stating that rebel property seized by the Union was forfeit to it.

But emancipation on this basis seemed to imply that the freedmen had indeed once been human property, an idea that Republicans, radical Republicans and Lincoln in particular, rejected on principle. Another worry troubled Lincoln as he considered the future: once the rebel states were readmitted to the union, would slaveholders be legally free to re-enslave the recently freed? From a practical point of view alone, what would stop them? An executive proclamation might help to secure the freedmen’s safety.

Only one cabinet member—Postmaster General Montgomery Blair—objected to emancipating the slaves of Southerners in rebellion (although Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase quibbled over using presidential proclamation as the mechanism). Blair was not ready to see the war for Union become a war for emancipation, and he warned Lincoln that the proclamation would alienate Democrats and slaveholders in border states. Secretary of State William Seward, however, objected not to the substance but to the timing of the proclamation.

The timing had everything to do with the course of the war. The Union had suffered serious setbacks by July of 1862. After the morale-boosting wins in western Tennessee—the captures of Corinth and Memphis, Fort Henry and Fort Donelson—and after the capture of New Orleans, the Northern public hoped that victory was imminent. General George B. McClellan began moving troops toward Richmond, threatening an attack on the Confederate capital. The Peninsula campaign came close to this goal—until McClellan cautiously pulled back. The new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee, opted to take advantage of McClellan’s indecision. In late June, in a series of battles called the “Seven Days,” Lee attacked McClellan’s sprawling forces at a critical point, severing the railroad line that ran supplies to the troops stationed within striking distance of Richmond. Meanwhile, efforts to take eastern Tennessee were stalled. These setbacks turned Northern optimism to dejection.

Seward advised Lincoln to wait for a union victory before announcing emancipation, lest his announcement seem the last stratagem of an administration incapable of defeating secessionists. European observers, who did not understand Lincoln’s constitutional qualms about ending slavery by executive fiat, would draw such a conclusion. The British, suffering from the disrupted transport of cotton to British textile mills, were debating whether to recognize the Confederacy. Some observers warned they awaited only confirmation that the Union effort was unwinnable before recognizing the Confederacy and helping them negotiate a peace. Border states, having already refused Lincoln’s repeated request that they undertake a program of compensated emancipation, were not ready to give up slavery; they would call the move desperate. So might Northern Democrats leery of living side-by-side with freedmen. Lincoln was immediately persuaded to wait. As he later told a delegation of clergymen who urged him to proclaim emancipation, to do so without a decisive victory to back him would do no good; he could no more enforce his proclamation than could the Pope who issued “a bull against the comet.”

The Military Victory That Gave the Proclamation Force

The victory Lincoln needed came on September 17, during one of the Confederates’ rare forays into Union territory. After winning the battle of Second Manassas at the end of August, Lee pressed the offensive and marched into western Maryland. Realizing that in a long war, the North’s superior resources would spell Confederate defeat, Lee hoped to win a quick and decisive victory on Union ground. This might persuade the North to begin peace negotiations. Lee also wanted to take his hungry and tattered troops out of an already ravaged Virginia and into a rural area with more food to glean. Many of Lee’s troops followed their commander in the belief that the citizens of Maryland were Confederate sympathizers and would willingly feed them. They did not realize that the farmers in the west of the state differed from those in the Tidewater region. Few owned slaves, most worked small family farms, and most were loyal to the Union.

In the rolling hills around Sharpsburg where the battle finally occurred, the farmers not only weren’t Confederate sympathizers; they were pacifists, members of a German denomination called the Brethren that espoused “nonresistance” and had forbidden slaveholding by its members in 1782 . The Brethren managed to clear out of the way before the battle joined, but any unharvested crops they left were ruined. Fighting was so fierce in one 24-acre cornfield that every stalk was sliced off by bullets. One farm—that belonging to Samuel Mumma—was burned by Confederates, who feared it could be used as a cover by Union sharpshooters. Years later, a Confederate major who survived the battle felt his conscience troubled, knowing that the family whose home was torched would have received no compensation for their loss, as it was not caused by federal troops. The major wrote the postmaster of Sharpsburg, asking to be put in touch with the family. As it turned out, the postmaster was Samuel Mumma, Jr. He replied forgivingly to the letter writer: “As for the farm you burned, we understand that you were ordered to do so.”

I read that story from a placard at the battlefield, which David and I visited in August. The Park service has laid out a circuitous route to take visitors on an hour-by-hour tour of the shifting course of battle on September 17. At each stop, there is a placard explaining events, surrounded by tall monuments. These commemorate the fallen in each state regiment. On the eastern side of the road, the monuments are dedicated to Union regiments, on the western side, to Confederates. Some placards tell stories of casualty rates near 50%; in the 1st Texas Division, 82% of the men who fought were killed. I thought of Lincoln’s admonition in March 1865 to Americans eager for the end of war:

“. . . If God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

Antietam’s ruined crops, piled corpses (estimated at 6300 to 6500), and 15,000 wounded made a deposit toward that payment. Overall, the Confederates suffered a casualty rate of about 25%; for Union forces, the rate was over 20%.

There were few decisive successes by either side in the day’s battle, although Ambrose Burnside dislodged defending Confederates from a bridge across Antietam Creek and caused them to abandon the heights overlooking it. Antietam was deemed a Union victory chiefly because Lee, after his army’s massive losses, opted not to renew the attack the next day and on the night of the 18th withdrew from the field. McClellan did not renew the battle either. But because Lee crossed the Potomac River and retreated into Virginia, McClellan claimed a victory, and the Northern press celebrated it as such.

The Preliminary and Final Proclamations

It was enough for Lincoln to move ahead with emancipation. On September 22 he issued the preliminary proclamation, which warned the secessionists that unless they returned to the Union by January 1, 1863, the people they held in slavery would be “then, thenceforth, and forever free.” News of the preliminary proclamation spread quickly among enslaved people near the Union battlelines, and many more attempted the flight to freedom (even as Southerners tightened the patrols that tracked escapees).

Issuing the final proclamation, Lincoln deleted the word “forever;” he had realized that his emancipation proclamation might well fall to a court challenge once the rebel states were back in the Union. It was also becoming clear that, as James Oakes writes in Freedom National, advancing Northern troops could never free all those held in bondage. The institution extended “over too many farms spread out over too many square miles.” A Constitutional amendment was the only solution.

After winning reelection in November 1864, Lincoln and a small army of Republicans and political operatives began gathering the Congressional votes needed to pass the Thirteenth Amendment through the House, where it had stalled the previous June. It passed on January 31, 1865. At last, a process was underway to amend the flawed Constitution. It began with the horrific battle at Antietam.

Bibliography:

John David Hoptak, The Battle of Antietam: September 17, 1862. Published by the Western Maryland Interpretive Association in cooperation with the National Park Service.

James M. McPherson, Antietam: The Battle That Changed the Course of the Civil War (New York: Oxford, 2002).

James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013).