George Washington on Political Parties

In 1792, as President George Washington neared the end of his first term in office, he was strongly contemplating retirement. Decades of service to his country had taken their toll on the aging statesman and Washington looked forward to a peaceful retirement at Mount Vernon. To that end, he asked James Madison to prepare a draft of a farewell address to be delivered to the country. Stepping down from office, however, was not in the cards, at least not yet.

Washington’s friends prevailed upon him to put himself up for the presidency again and, after some resistance, he acquiesced. His second term of office, though, was a grueling affair for Washington. Newspapers representing the emerging Democratic-Republican opposition party vilified Washington in the press and he grew tired of the hardships of politics. His health was also starting to fail and this solidified his decision to retire in 1796, at the end of his second term. The Constitution at that time allowed a president to run for reelection as many times as he wanted to, but Washington thought that two terms of office was sufficient. Taking office for more than two terms created the risk of a president for life, and so Washington thought that his two terms in office would set an important precedent for the future.

As Washington’s second term drew to a close, he again contemplated a farewell address to the American people to express his hopes and fears for the young country. Since Madison was then leading the opposition to Washington and the Federalists in the House, Washington turned to Alexander Hamilton to complete the earlier draft that Madison had begun. Being one of Washington’s most trusted aides, Hamilton was only too happy to comply. The product became one of the most famous addresses in American history, exhibited by the fact that the Address has been read in the U.S. Senate every year since 1893. Some scholarly debate exists over whose ideas are expressed in the Address, since Madison and Hamilton had important roles in writing it. Most research, however, has concluded that the Address contained Washington’s ideas in Madison’s and Hamilton’s writing. Interestingly, Washington never delivered the Address in person. Instead, it was published in the Philadelphia American Advertiser on September 19th, 1796. From there it was spread throughout the country via newspapers.

Despite the divisiveness in the country at the time, the Farewell Address was received warmly by the country. Citizens expressed sorrow about Washington’s retirement from public life, but also gratitude for his service and for his many sacrifices to his country. Indeed, the speech helped solidify Washington’s reputation as “father of his country” and a man who put love for the American people above his own self-interest. Unfortunately for Washington, his much-anticipated transition into private life did not last long and he died in 1799.

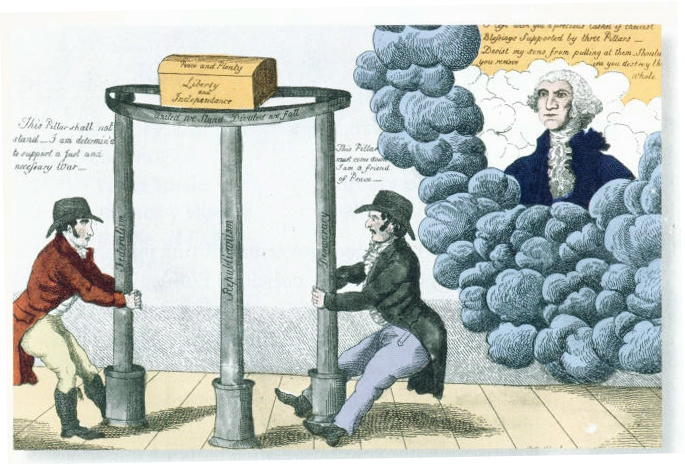

Washington touches on a number of themes in his Address, but of particular interest is his concern about political parties. Like the other founders, Washington considered parties to be the bane of republican government. Parties were factions that threatened to divide the electorate into competing groups who might use violence to advance their interests. Parties might also disrupt the separation of powers, especially in the case of unified government where loyalty to a party could interfere with the system of checks and balances. Parties also threateend to stand in the way of effective representation, with elected officials tempted to represent only fellow party members and to leave opposition groups without a voice in government. Taken together, it is little wonder that the framers did not want parties participating in American politics. Instead, the founders tried to create a nonpartisan political system.

Despite their wishes, the framers’ nonpartisan system did not last. By 1793, the first semblance of a party system had formed in America and two parties began to engage in competition with each other. How did this happen just four years after the nonpartisan Constitution was ratified? The best answer is that parties are inevitable in republican government. More precisely, republican government does not work well without being buttressed by political parties. Parties mobilize voters and encourage voter participation. They help build support for officeholders and serve as conduits of communication to the people. They allow minorities to form coalitions to create majority rule. And they serve as schools of democracy where citizens learn the art of association and become attached to governing institutions.

Washington, however, coming from the older generation, was not ready to embrace the positive things parties could bring to republican government. In the Farewell Address, he warned against the danger of parties and how they need to be checked in the future. On one hand, Washington cautions the nation about geographical divisions such as North versus South and East versus West. One of the expedients of party to acquire influence, he wrote, “within particular districts, is to misrepresent the opinions and aims of other districts. You cannot shield yourselves too much against the jealousies and heart burnings which spring from these misrepresentations: they tend to render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together by fraternal affection.” Sectionalism would pull the country apart and parties that tried to exploit sectionalism were to be greatly feared.

Even worse than sectional parties, though was the dangerous effects of the spirit of party. Washington believed that beyond factional strife, parties could lead to the establishment of despotism. The alternate domination of one faction over another, he wrote, “natural to party dissention, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries, which result, gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual.” Given the danger that parties posed to republican government, Washington argued it was best to try to discourage and restrain them.

Washington was mostly unique among the founders in never reconciling himself with political parties and never acknowledging the positive things that parties can bring to republican government. Although he probably would have conceded that parties were inevitable, he argued for keeping them under restraint and limiting their interference in the political process as much as possible. It is hard to know, of course, what Washington would say about the parties and party system we have today, since they are so different from the parties in his day and the kind of parties he worried about, but many would say that Washington’s caution about parties still maintains some relevance.

Eric Sands is Associate Professor of Government at Berry College and a member of our MAHG faculty. He is the author of several books about political parties, including Teaching American History’s CDC volume, Political Parties. He will be conducting two upcoming free webinars on political parties, one on Wednesday, September 14th and the other on October 26th.