Henry Adeoye Teaches Citizenship

Henry Adeoye, an immigrant to America from Nigeria, teaches American history to eighth graders, most of whom are growing up in families who immigrated to America from Mexico or Central America. Adeoye also teaches the value of American citizenship to his students, a large percentage of whom come from low-income families. To those who appear uneasily caught between America and their family’s nation of origin, Adeoye offers a pep talk. “Most of us here are immigrants,” he says. “You don’t see me flying a Nigerian flag on my desk, do you? We came here because, where we came from, there was no security over there. You are here, you are safe, and you have a nice school and free lunch! I went to school in Nigeria for twelve years and never got free lunch one day.

“When your parents arrived here, they had to hit the ground running, in order to take care of you. They didn’t have the choice to have an education. But you do have that choice. We’re giving you that opportunity. You should take pride in America.”

Adeoye’s Immigrant Experience

Over two decades ago, when Adeoye himself arrived in Houston, he needed “to think fast” on how to make a living. He had already earned two university degrees, yet his training in philosophy and in international law and diplomacy didn’t qualify him for the opportunities open to him. Having taught English, religious studies, and government for three years in Nigeria, he wondered about secondary school teaching. To “get a feel for the American classroom, without being in charge of it,” he took a position at a high school as a teacher’s aide.

He found American students far less obedient and respectful of authority than Nigerian students. This did not deter him. The lively interactions he witnessed between American teachers and students made teaching work more interesting than he had found it before. Working in classrooms in a range of disciplines, he realized that “teaching math is not for me!” American history, however, interested him a great deal—much more than the history he had taught in Nigeria. After watching a history teacher capture students’ imagination in a lesson on President John F. Kennedy, he realized he wanted to teach social studies.

Adeoye enrolled in a teacher certification program offered through the Cypress-Fairbanks branch of the Lone Star Community College system. He became certified to teach special education from early childhood through 12th grade.

Teaching in a Changing School Environment

In 2005, Adeoye landed a job in the social studies department at Moorhead Junior High School in Conroe (a suburb of Houston). He has taught there ever since. Currently he teaches six sections of the early half of American history (from 1607-1877). The students he teaches range in readiness; some are in regular education, others in Honors, others in special education. With his Honors classes, he can dive into primary source analysis in depth.

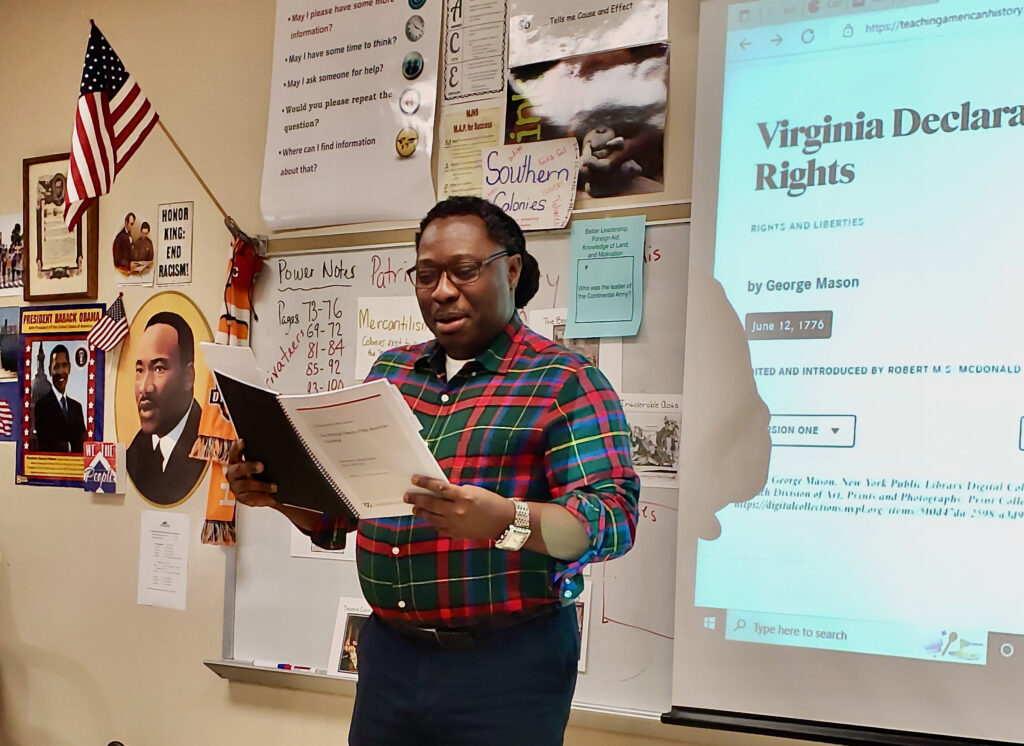

Over the years, demographics at the school have shifted, a majority white student body becoming majority Latino. Adeoye’s teaching approach has also changed. The transformation began when he started attending seminars offered by Teaching American History. “They opened my eyes to the value of the primary source in teaching history,” he says. Participating in TAH seminar discussions helped him figure out how to incorporate such sources in his teaching. He relied less on the textbook and spent more classroom time helping students read the words of those who lived in the past.

It helped a great deal to learn that TAH offers a free online library of primary documents. Now he knows where to find the documents that will enliven a lesson, “without searching all over the internet.”

Committing to Further Education

Last spring, Adeoye attended a weekend colloquium in Northampton, Massachusetts on “The Political Theory of the American Founding.” Taught by Professor Jason Stevens, the seminar covered the Declaration, the Constitution, and several Federalists’ and Antifederalists’ arguments. It also included later reflections on the founders’ political convictions: Lincoln’s Fragment on the Constitution and Union, and his Gettysburg Address; Woodrow Wilson, “The Author and Signers of the Declaration”; and Calvin Coolidge’s Speech on the 150th Anniversary of the Declaration. “The seminar got me really thinking about the founding documents,” Adeoye said.

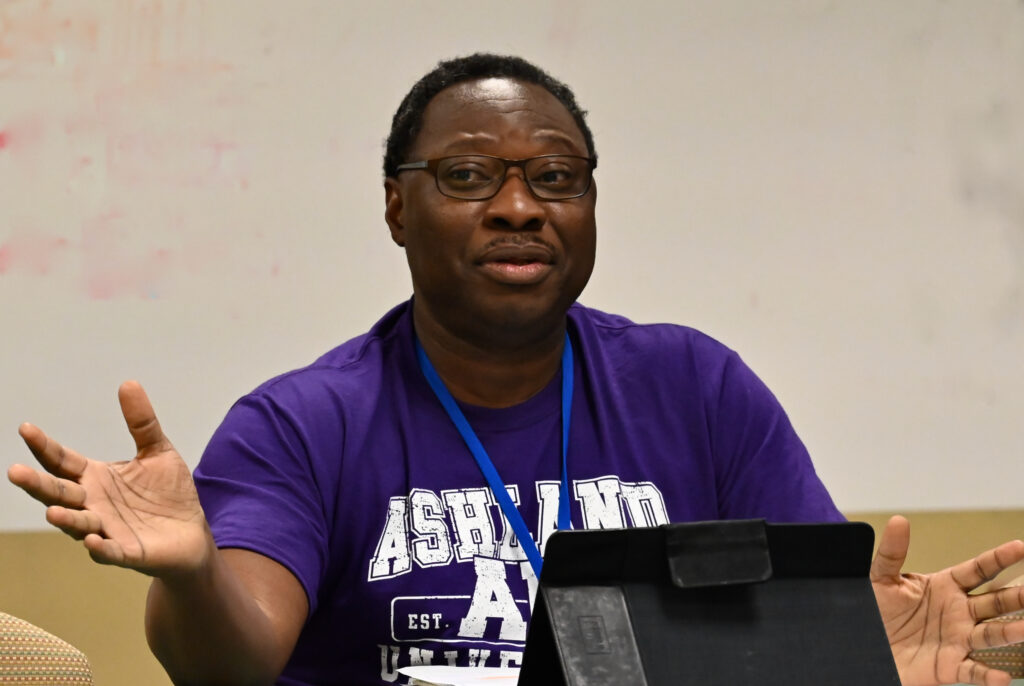

When Professor Stevens spoke of the MAHG program, Adeoye was intrigued. He inquired further, and Stevens encouraged Adeoye to enroll. Soon MAHG Director Christian Pascarella was advising Adeoye of scholarship opportunities. Adeoye began the program in July, attending three week-long sessions of the summer in-residence program at Ashland University.

Each week, teachers participate in sixteen 90-minute seminar discussions of primary documents on a specific era or theme in US history or government. Each hour-and-a-half discussion spans 40 to 60 pages of reading; teachers are advised to complete as much of the reading as possible before the week begins, so they may spend evenings reviewing the readings for the following day. “Three weeks was a long time” to spend in this intense kind of study, Adeoye said, “but I enjoyed every minute of it.”

He found the professors engaging. Drawn from a wide variety of specialty areas and from schools all over the country, they offered a variety of perspectives and teaching energies. He enjoyed Professor Joseph Fornieri’s passionate interest in Lincoln’s statesmanship; Professor Robert MacDonald’s deep knowledge of the early Republic, from a Jeffersonian perspective; and Professor Jeremy Bailey’s philosophic insights into the evolution of the American president’s role and powers. “I can’t wait to go back next summer,” Adeoye said.

An Inspirational Moment

Each summer MAHG session features a special buffet dinner on Sunday, the first night of the week, with students sitting in conversational groups at round tables. No one dresses up for this occasion, yet the cloth-draped tables and formal place settings communicate to all a thoughtful welcome. As dessert is served, program staff and faculty are introduced and procedures for the week reviewed. This year, the first night of Session Two fell on Independence Day. To celebrate the occasion, MAHG Program Chairman John Moser invited volunteers to join in reading the Declaration aloud. One by one, teachers rose and walked to the microphone, reading several sentences of the document before passing it on to the next volunteer. Adeoye read the passage,

Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such now is the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. . . .

Over a hundred Masters students, faculty and staff listened intently, until the last volunteer read:

And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred honor.

Adeoye, moved by this experience, went back to Texas determined to share it with his own students.

What Self-Government Entails

He began preparing the ground soon after the year began, presenting students with excerpts of the Magna Carta, the Mayflower Compact, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut, Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense, and John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, often cited as a source for the Revolutionary generation’s political ideals. He spoke about the Stamp Act and other instances of “taxation without representation” that roused the American colonists to rebel. Finally, the class began dissecting the Declaration, sentence by sentence.

“How do we give our consent to be governed?” he asked students. When students ventured uncertain answers, Adeoye pointed to a sign on the wall of his classroom, showing a word printed in bold letters—V O T E. “That’s your consent,” he told them. “I’m not teaching you history simply for you to know the story. When you guys turn 18, I strongly encourage you to be responsible citizens—to vote. Don’t say, ‘My vote doesn’t count.’ If you stay at home, those who go to vote may elect someone who does not represent your interest.”

“What if we don’t like either candidate?” a student asked.

“The only advice I can give you is the moral advice I apply in all situations,” Adeoye replied. “If you are faced with a choice between evils, choose the lesser! But in order to decide which candidate better represents your interests, you must seek out information about them. Watch the news. Research their policy stances. Don’t base your choice on the candidate’s skin color or ethnic identity. Base it on their political agenda.”

Adeoye keeps driving home the message of a citizen’s responsibility. His goal is that, by the time his students have worked their way carefully through the entire Declaration, they will read it aloud with pride—not as views unique to Jefferson, but as, in Jefferson’s own words, “an expression of the American mind.” He hopes they will understand the significance of the pledge the American revolutionaries made: that “in signing that document, they were signing their lives away” in the event their effort failed.

Being a citizen “is not just about yourself and your own rights,” Adeoye says. “Recently we discussed the experience of the soldiers at Valley Forge, how they fought without supplies. I told students, ‘Those people did not live to enjoy the freedom you enjoy today. They sacrificed so that you would enjoy it. So, we must try to continue that legacy.’”