Henry Grady's Vision of the New South

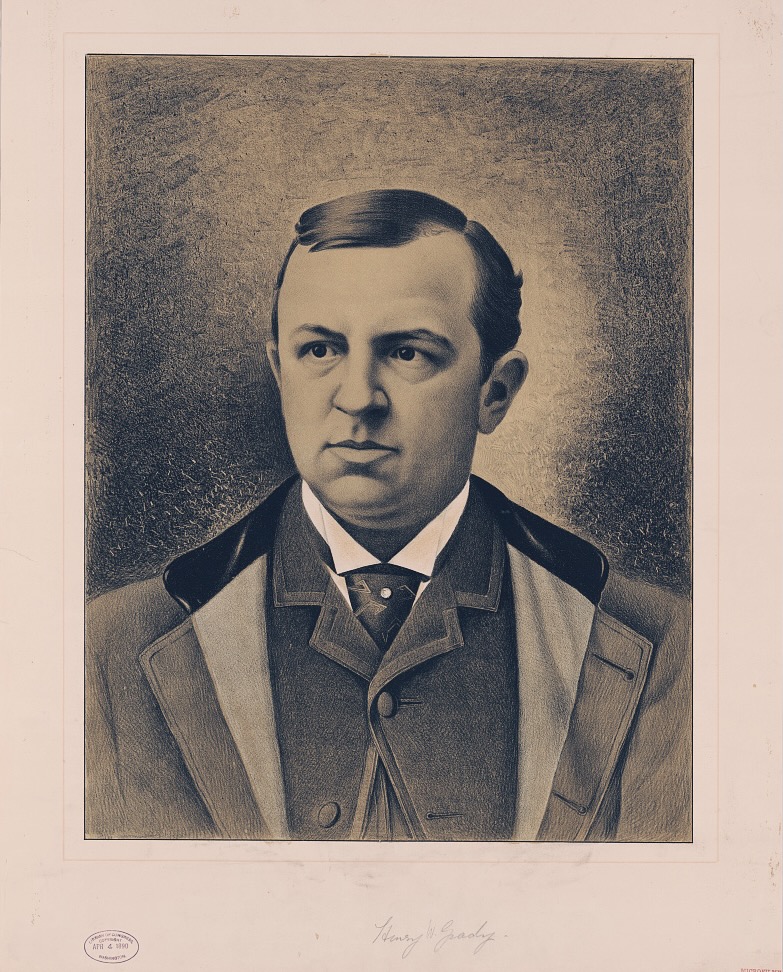

When I moved to Charlotte, NC, in 1986, I visited local museums to learn about the city. One museum caught my eye – the Levine Museum of the New South. Its permanent exhibit – Cotton Fields to Skyscrapers – “uses Charlotte and its 13 surrounding counties as a case study to illustrate the profound changes in the South since the Civil War.” The “New South” – a term Atlanta newspaperman Henry W. Grady coined in a speech to the New England Society of New York on December 21, 1886 – is familiar to many American history teachers. In his speech, Grady, the first southerner to speak to the Society, claimed that the old South, the South of slavery and secession, no longer existed and that southerners were happy to witness its demise. He refused to apologize for the South’s role in the Civil War, saying, “the South has nothing to take back.” Instead, the dominant theme of Grady’s speech, according to New South historian Edward L. Ayers, “was that the New South had built itself out of devastation without surrendering its self-respect.” Tragically, Grady and most of his fellow white southerners believed maintaining their self-respect required maintaining white supremacy.

Grady, then the 46-year-old editor-publisher of the Atlanta Constitution, was one of the leading advocates of the New South creed. In New York, he won over the crowd of prominent businessmen, including J.P. Morgan and H.M. Flagler, with tact and humor. He praised Abraham Lincoln, the end of slavery, and General William T. Sherman, whom he called “an able man” although a bit “careless with fire.” Grady reassured the northern businessmen that the South accepted her defeat. He was glad “that human slavery was swept forever from American soil” and the “American Union saved.” He urged northern investment in the South as a means of cementing the reunion of the war-torn nation. He claimed progress in racial reconciliation in the South and begged forbearance by the North as the South wrestled with “the problem” of African Americans’ presence in the South. Grady asked whether New England would allow “the prejudice of war to remain in the hearts of the conquerors when it has died in the hearts of the conquered?” Grady’s audience cheered his call for political and economic reunion – albeit at the cost of African American rights.

The term “New South” was used in the 20th century to refer to other concepts. Moderate governors of the late 20th century – including Terry Sanford of North Carolina, Jimmy Carter of Georgia, and George W. Bush of Texas – were called New South governors because they combined pro-growth policies with so-called “moderate” views on race. Others used the phrase to summarize modernization in southern cities such as Charlotte, Atlanta, Richmond, and Birmingham, and the region’s increasing economic and demographic diversity. However, all uses of the term have suggested the intersection between economic development and racial justice in the South during Reconstruction, the Jim Crow Era, the Civil Rights Era and today.

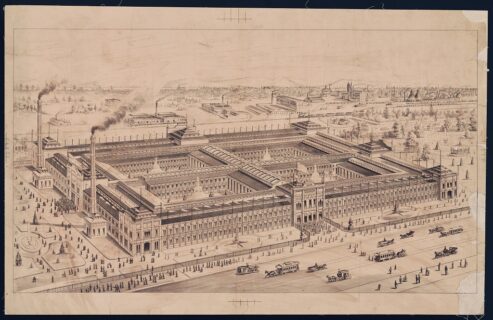

This intersection included three main ideas for Henry Grady and other southern boosters of the New South in the 1880s. First, the Old South of slavery and secession was gone. Two, a New South, of unlimited economic potential welcomed investments from northern capitalists to transform the region into an industrial powerhouse. Third, and by no means last, the white South was best qualified to answer the question: what share in the new economy would be given to the formerly enslaved people?

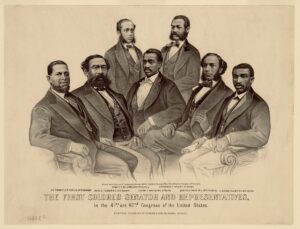

In his New York speech, Grady described the South’s post-Civil War success, the long road ahead, and the economic disparity between the North and South. He believed this disparity threatened reunion. Though he did not deny his belief in white supremacy, Grady was not as blunt when talking to New Yorkers in 1886 as he was in Dallas, Texas, one year later. Speaking to his fellow southerners, Grady cited two problems the South faced in 1887, the “Race Problem” and the “Industrial Problem.” In addressing the “race problem,” Grady bluntly declared: “the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards – because the white race is the superior race.” Grady’s wording reveals his fear that the Black population of the South, if granted actual voting rights, could wield significant power due to its sheer size. The Texans Grady addressed in 1887 had less to fear from this perceived threat than the whites of his native Georgia. Texas whites comprised over 70% of Texas’s total population, while African Americans in Georgia constituted 47% of its population. South Carolina’s population was not majority white until 1920. “The worst thing … that could happen” Grady believed, would be an alliance between white and black voters threatening the fragile stability of the South as it continued its recovery from the Civil War.

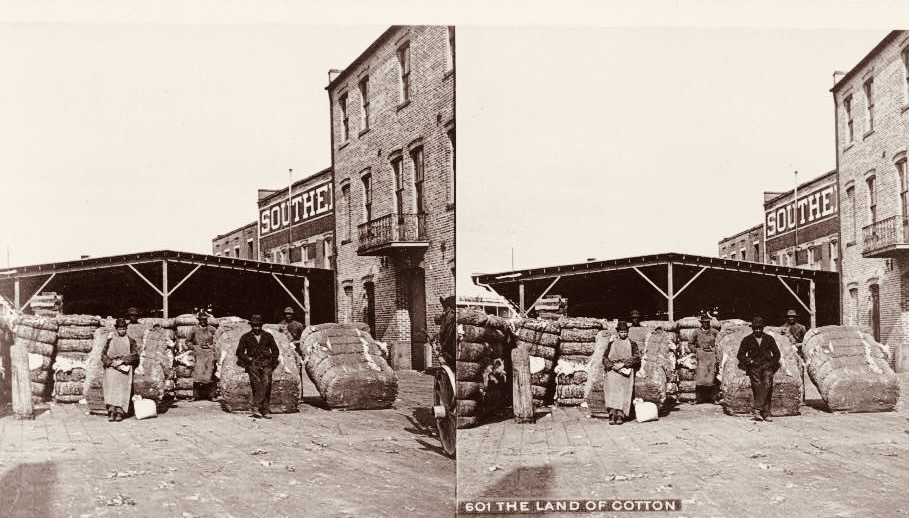

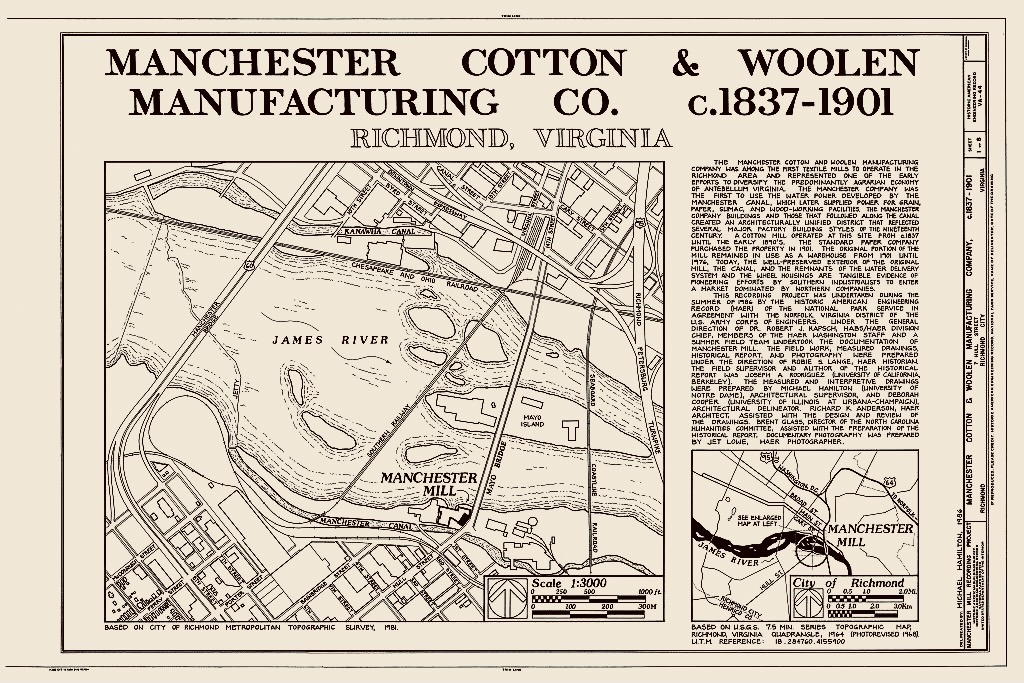

In addressing the economic challenge, Grady bragged to his Texas audience about the South’s enormous growth. Cotton production was up. So was timber, wool, and iron. What the South now needed were Southern factories hiring southern workers that converted cotton into textiles, timber into furniture, and iron into tools.

From which racial group did Grady expect Southern factories to hire the labor they would need? In December of 1889, Grady returned to the North to deliver a speech in Boston’s Faneuil Hall on “The Race Problem in the South.” Grady argued that African Americans in the South had lost faith in the promises of Reconstruction. “Discouraged and deceived, [the Southern African American] … realized at last that his best friends are his neighbors, with whom his lot is cast and whose prosperity is bound up in his.” Did Grady expect that Black workers might eventually be hired alongside white workers in the new Southern factories? It is hard to say, because this speech was Grady’s last. Upon returning from Boston, the newspaperman developed pneumonia and died on December 23, 1889. He was only 49 years old.

American history teachers will note the similarity between Grady’s Boston rhetoric and that of the prominent southern African American leader Booker T. Washington. In a speech excerpted in Teaching American History’s Core Document Collection: Race and Civil Rights (now available in the tah.org bookstore) known as the “Atlanta Compromise” speech, Washington used the metaphor of a ship desperate for fresh water and finding it after casting its buckets down where it was, unknowingly at the mouth of the Amazon River. Washington urged both blacks and whites to cast their buckets down in the South to draw up the fresh water of economic progress. But he did not suggest that blacks and whites work alongside each other in the same jobs. His Tuskegee Institute gave vocational training to Southern blacks, teaching skills that he hoped would raise the price of their labor, or even allow them to start their own businesses.

Today, Washington receives a lot of criticism for this speech. He is viewed as an accommodationist, someone willing to accept political and social discrimination in exchange for Black economic progress. However, Peter Myers’ excellent introduction to Washington’s speech in TAH’s Race and Civil Rights document volume suggests readers note Washington’s subtle rhetoric in opposition to the South’s racial status quo. One example is Washington’s advice to make friends with the surrounding white race “in every manly way.” Perhaps Washington did not believe that manly acceptance of friendly relations required African Americans to accept being denied the ballot. Arguably, if African Americans gained economic power through their skilled labor, they might eventually compel the white power structure to grant them political power as well. Perhaps Washington was dropping such hints to African Americans in his audience while seeming to reassure his white audience that Blacks had no such ambitions.

American history teachers may challenge their students to think about the concept of the New South with some of the following questions. What would Henry Grady say if he toured the Levine Museum’s exhibit and downtown Charlotte today? Would he be surprised to learn that national financial institutions such as Bank of America now make Charlotte their headquarters? Would he be surprised that the economic growth the South experienced in the late 20th century was propelled in large measure by the integration of the Southern work force? How would Grady react upon learning that the Staff Historian of the Levine Museum of the New South was Dr. Willie Griffin, an African American scholar native to the South? Would he renounce the white supremacy he endorsed during his lifetime as the political nonsense required of white public figures of his era? Would Grady claim to be proud of the racial progress the South has made, and recognize the work that remains?