The History of "Court-Packing"

Roosevelt’s “Court-Packing” Plan

For many students, the “Fireside Chat on the Reorganization of the Judiciary” (more memorably recalled as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “court-packing plan”) brings up, for the first time in their study of US History, questions about the actual number of Supreme Court justices. Most have not yet taken a Government course, and have never noticed that the Constitution does not specify how many justices the Court should have. The high drama and political intrigue behind the reorganization plan capture students’ imaginations, quite understandably, but can also lead to a misreading of context. That is to say, students often mistakenly believe that FDR’s March 1937 Fireside Chat is the first introduction of politics into SCOTUS numbers: because this is the first time they are hearing about it, they think this is the first time that it happened. And yet the story of changing SCOTUS numbers (to say nothing of changes on the federal bench at large) is full of fascinating political tactics.

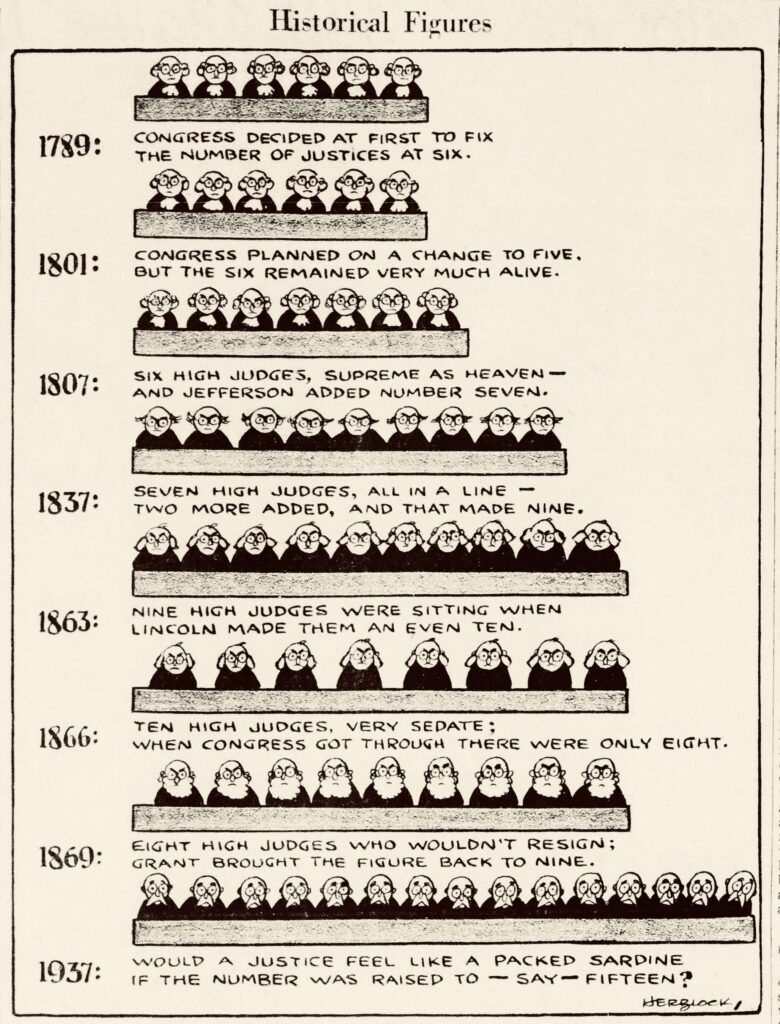

“Historical Figures”

To introduce my students to the fuller context of political maneuverings behind SCOTUS numbers, I like to pair FDR’s Fireside Chat with a political cartoon from 1937, “Historical Figures” by Herblock (the pen name of artist Herbert Block). Herblock sketches out the changing number of justices on the Supreme Court from the time of its creation until FDR’s proposed reorganization in 1937. He adds a sing-song rhyme to convey a memorizable history lesson. While “Historical Figures” gives us the basic narration, some exploration and explanation of context allows us to see the politics behind the additions (and occasional subtractions) of justices on the Court.

“Congress decided at first to fix/the number of justices at six,” Herblock begins, referring to the Judiciary Act of 1789.

“1801: Congress planned on a change to five, but the six remained very much alive.”

To the degree that students know anything about the political intrigue of John Adams’ 1801 lame duck period, they know about the “Midnight Judges Act” leading to Marbury v. Madison, but not about that act’s intent to reduce the number of SCOTUS justices upon the next vacancy. This stipulation was repealed by legislative action in the first full year of Jefferson’s presidency.

“1807: Six high judges, supreme as heaven — and Jefferson added number seven.”

“1837: Seven High Judges, all in a line — two more added, and that made nine.”

“Court-Packing:” A History

Jefferson’s Efforts to Influence the Supreme Court

Initially students tend to find these additions to the SCOTUS bench — up to seven in 1807, and to nine thirty years later — uncontroversial, because these legislative acts matched the number of SCOTUS justices to an expanded number of federal circuit courts. After all, this is a time when SCOTUS justices “rode the circuit,” because the original Judiciary Act of 1787 also stipulated that they would act as regional judges when away from the highest court in the land. Nonetheless, Jefferson’s administration was not devoid of political contention around judges. President Jefferson lobbied for the impeachment of SCOTUS Justice Samuel Chase (successfully, though this impeachment did not end in his removal from the bench).

Jackson and the 1837 Judiciary Act

In the case of Andrew Jackson’s appointments, the timing of the 1837 Judiciary Act — on Jackson’s last day in office — raises students’ antennae. Jackson was allowed to make the nominations under the act, since it took effect immediately. Strikingly, all five of Jackson’s second-term SCOTUS appointees came from slaveholding states, at a time shortly before anti-slavery politicians would begin to complain about the political “slave power” dominating federal affairs.

The Civil War and the Supreme Court

“1863: Nine high judges were sitting when/Lincoln made them an even ten.”

“1866: Ten high judges, very sedate; when Congress got through there were only eight.”

“1869: Eight high judges who wouldn’t resign; Grant brought the figure back to nine.”

The twists and turns of Civil War & Reconstruction SCOTUS reorganizations reflected the politics of slavery, of war, and of civil rights. The 1863 reorganization added a 10th circuit and SCOTUS judge while also reducing the number of circuits representing slaveholding states. This effort was clearly geared towards reforming an institution that had come to be seen as (in the words of the January 3, 1862 edition of Minnesota’s Weekly Pioneer & Democrat) “the last stronghold of Southern Power”. Lincoln wanted to counter judicial obstruction of the Union effort. Three years later, in the Judicial Circuits Act of 1866, Congress passed a planned reduction to seven justices that denied Andrew Johnson the opportunity to appoint anyone to the high court (in the midst of tense congressional/presidential arguments over Reconstruction that would lead to Johnson’s impeachment two years later).

As Herblock’s poem indicates, SCOTUS never quite reduced down to seven, and the Judiciary Act of 1869 returned the number of seats to nine. The single addition was crucial, as SCOTUS had previously declared key Reconstruction economic plans (about issuing paper currency) unconstitutional; the reconstituted nine-member court reheard the key case and reversed the decision by a single vote.

Roosevelt’s Plan

“1937: Would a justice feel like a packed sardine/if the number was raised to — say — fifteen?”

Herblock’s final rhyming question brings readers to his present moment, and reminds us (along with his amusing visual) of just how jarring FDR’s plan was. But, however jarring it may have been, FDR’s proposed 1937 judicial reorganization did not inject politics into SCOTUS numbers for the first time. FDR’s by-then established practice of talking to the public about policy through radio addresses may have made it seem utterly novel, but zooming out to survey the broader timeline shows us that almost every proposed reorganization of the federal judiciary has entailed a certain amount of political strategizing. Showing students that political jockeying over the Supreme Court is not a “modern” development does not require us to condone or condemn any specific reorganization. Instead, it reminds students that it isn’t weird that parties and politicians (in FDR’s time or ours) seem to treat the Supreme Court as a political football. In fact, it might be a more significant aberration if they didn’t.

Our newest CDC volume, The Judiciary, will be available in our bookstore in May. This collection of documents presents an array of views on the role that the courts should play in American life and how they should interpret the Constitution and our laws.

Additional Sources

Federal Judicial Center: www.fjc.gov

Irons, Peter. The History of the Supreme Court: Course Guidebook. Chantilly, VA: The Teaching Company, 2003.

Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States, “Draft Final Report.” December 2021