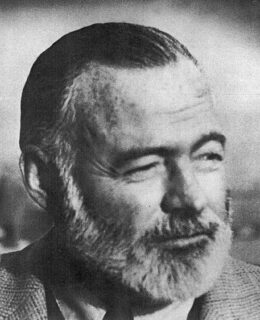

Dan Monroe: History & Hemingway

Teachers will have two opportunities to explore the work of writer Ernest Hemingway in the upcoming weeks. Professor Dan Monroe, who is the John C. Griswold Distinguished Professor of History at Millikin University in Decatur, Illinois, and MAHG faculty member, sees Hemingway not only as the most important American literary voice of the twentieth century but also as a window into an era of war and social upheaval. We asked Professor Monroe to chat with us about his interest in this iconic American author.

What inspires you to offer a course on Hemingway in the MAHG program?

I find Hemingway endlessly fascinating both as literature and for his portrait of the first half of the 20th century. I have a minor in American literature. But as a historian, I believe I can offer a richer and deeper analysis of Hemingway’s fiction than that offered in many literature seminars; I can tease out the cultural and historical ethos reflected in Hemingway’s fiction. “Wine of Wyoming” offers a good example. The story describes a French couple who has immigrated to the US and moved to Wyoming, where they open a hotel and make wine. Prohibition comes along, and they are prevented from doing this anymore. The story illustrates the social and historical background at the end of the 1920s and the struggles immigrants faced in assimilating into a Puritanical cultural environment.

What texts will you ask students to read for the summer MAHG course?

Two novels: A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls, plus selections from Hemingway’s short stories.

For the Saturday webinar, will you ask teachers to read some of Hemingway’s work ahead of time?

Five short stories are recommended reading: “Soldier’s Home,” “Big Two-Hearted River, Part 1,” “Wine of Wyoming,” “One Trip Across,” and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” If participants read these ahead of time, the webinar will be more productive, since we’ll be able to discuss them together.

Have you done research on Hemingway?

There is an international conference on him every two years, and I try to go to as many as I can and present papers on the historical and cultural context of his work. I’ve published an article based on a presentation I made at a conference at Key West. As you know, in the literary field for the last 25 or 30 years, it’s all about deconstructing texts—finding implicit racism or sexism or some other “ism” in the writing. I think the historical context I can bring to Hemingway is more interesting and less tiresome to people.

What is an example of the history Hemingway’s work illuminates?

A Farewell to Arms shows the post-World War I disillusionment with war. So many casualties came out of the war, yet there was no fundamental change in European borders, so it seems that nothing was achieved by the conflict. In the little-known short story, “Black Ass at the Crossroads,” Hemingway describes the carnage associated with an ambush set-up to kill German soldiers retreating to Aachen, Germany, in the closing months of World War II. It is a melancholy reflection on the awfulness of war, even amidst the triumphalism usually associated with that just war.

Hemingway’s spare style now seems pretty natural to us, but he’s largely responsible for changing our sensibility on that. How was his style received when he began writing?

His work was subject to a mixed critical reception. Many found it wonderful and gripping, although there were a few—I think they were wrong—who found it too spare, like he had denuded the trees of leaves and clipped off the branches. There were also those who thought his subject matter stepped over the boundaries of propriety and the accepted mores, since he alludes to subjects like abortion and homosexuality and gives cryptic descriptions of sexual activity—subjects not treated in polite literature of the time.

In understanding Hemingway, is it important to know that he worked first as a journalist?

Absolutely. If you look at Hemingway’s journalism in the 1920s, you will see a lot of his stylistic experimentation there. He is using simple declarative sentences, without a lot of adjectives and adverbs. He is actually doing what journalism should do, reporting rather than commenting. Occasionally, however, he cannot resist a comment. Hemingway was asked to interview Mussolini for The Toronto Star. He found Mussolini a kind of buffoon. He comments on what Mussolini was wearing, saying “It is hard to take seriously a man who wears a black shirt with white spats.” Mussolini was dressed like a clown—and yet by this time he was ruling Italy and would soon be dictator.

Hemingway spent a lot of time overseas. Why? What do you see as his relationship to the land of his birth? Was he uncomfortable here, or is it rather that he sought experience he could not get here?

Hemingway does live an expatriate life, not only in Paris in the 1920s. I think he was always in search of evocative places. But also, like many writers and intellectuals, he liked to go off by himself—to the isolated island of Key West in the 1930s, which might as well have been a foreign country at that time, or to a home in the hills in Cuba in the 40s and 50s. I’ve been through his published letters, and I don’t find any distaste for the US; and, indeed, in some of his stories you see loving descriptions of the landscape of the American West or of Michigan. Hemingway was not like some expatriate writers—say, Ezra Pound—who chose life abroad because they hated the American political system and American culture.

Does Hemingway take an American perspective with him when he goes abroad?

If you talk to Europeans, you find that they view Hemingway as the archetypal American writer. They see A Farewell to Arms as a distinctly American reaction to Italy at the time of World War I.