How Women Won the Right to Vote

Whenever I begin classroom conversations about women’s suffrage, I always play a “man on the street” clip in which a reporter stands on a busy sidewalk, asking college students and adults to sign a petition abolishing women’s suffrage. Throughout the clip, people sign this petition while reiterating their support of women. Why are they signing to take away suffrage while in the same breath proclaiming their unwavering loyalty towards women? Because they do not know what the term “suffrage” means. The term suffrage has nothing to do with the word “suffer;” it derives from a Latin word for a tablet or fragment of pottery once used as a ballot. The founders, in the 1787 Constitution, used the word to mean the right to vote.

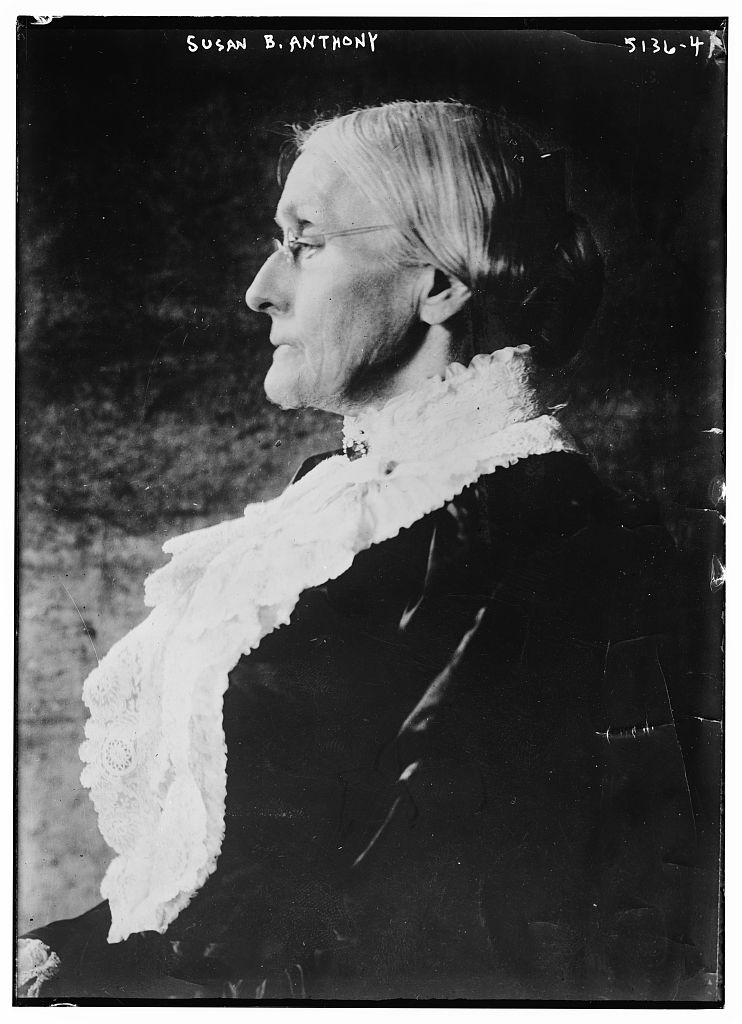

My students go into an uproar when we break this video down. I tell them, “You know their social studies teachers are somewhere crying right now. And if I see you on this show in a few years, I’ll be crying too!” Then we get into the start of the women’s suffrage movement—which can be traced back at least as far as Abigail Adams’ plea to her husband John to “remember the ladies” who were helping support the revolution. But one might also place the starting point of the movement with Susan B. Anthony.

The 19th Amendment, ratified on August 18th, 1920, has been called the Susan B. Anthony amendment. It declares that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Ironically, Anthony, a social reformer and a woman’s rights advocate, believed women should be entitled to vote without this amendment. As US citizens, they possessed the right to government by consent, just as male citizens did. Anthony was aggressive in her mission for women’s voting rights, even challenging New York laws during the 1872 presidential election. She persuaded an election official in her hometown of Rochester, NY to register her to vote, arguing that the 14th Amendment granted unabridged rights to all citizens born within the United States. Then she (and fourteen other women) cast their ballots on November 5, 1872. Two weeks after the election, Anthony was arrested for voting illegally. After being convicted and sentenced to a $100 fine, Anthony said, “I shall never pay a dollar of your unjust fine,” and she did not pay.

The official response to Anthony’s bold move demonstrated the need for a national amendment. The 19th Amendment was first proposed in 1878 but failed several times to make it out of the House. The proposed amendment did not pass the House and Senate until 1919. It took another thirteen months before the necessary three quarters of the states ratified it, making it an official part of the Constitution on August 26, 1920. Why did it take so long to grant women the right to vote?

Our nation is founded on the principle that each citizen has a voice, and the way to exercise that voice is through voting. James Otis wrote his famous line, “Taxation without representation is tyranny” in response to the Stamp Act of 1765. These words were echoed countless times throughout the American Revolution and the American founding. But why were women left out?

Many of the arguments against women’s suffrage relied on the concept of virtual representation, which meant that women and their children were already virtually represented by their husbands and fathers. The suffragette argument against this was based on the concept of republican government. Women’s rights advocates from Anthony forward believed that they had the right to argue for self-representation, just like Otis and the rest of the founders did. Opponents (some of whom were women) countered that allowing women the right to vote would hurt the family. They feared that female voters would change marriage and property laws, making it easier to get divorced. Allowing this might destroy gender roles, effacing the “natural differentiation of function” between men and women with “identity instead of division of labor.” This, they thought, would unravel society. For years, these arguments were woven into the opposition to women’s suffrage. It was the American entry into World War I that gave women the final push to secure their voting rights.

The late 19th and early 20th century saw the rise of the Progressive Movement, which proposed ways of reforming areas of American life in which too much inequality had developed due to industrialization. Yet at the same time, industrialization had undermined many of the traditional arguments against women’s suffrage, because many women began leaving their families during the day to work in factories. It became harder to justify denying the vote to a part of the population who were working independently from their male family members, fighting their own battles in the marketplace.

Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat and a progressive, was elected in the 1912 presidential election because of a split within the Republican Party. While in his first term, he did not take any public stance for women’s suffrage. However, after a vote for women’s suffrage in New Jersey in October 1915, Wilson publicly stated, “I believe the time has come to extend the privilege and responsibility [of voting] to the women of the State, but I shall vote . . . only upon my private conviction. I believe that it should be settled by the State and not by the National Government.” That vote for women’s suffrage in New Jersey failed.

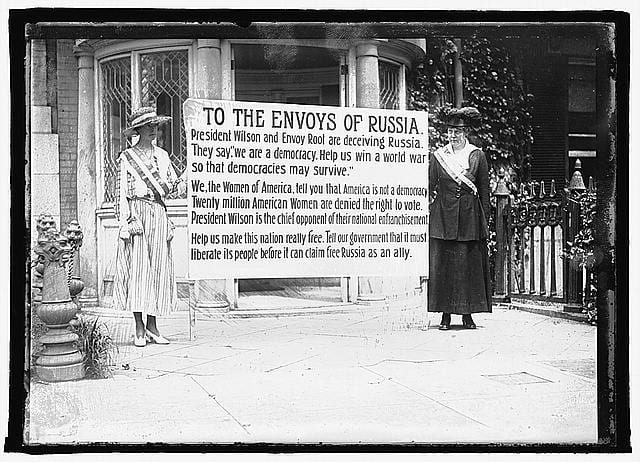

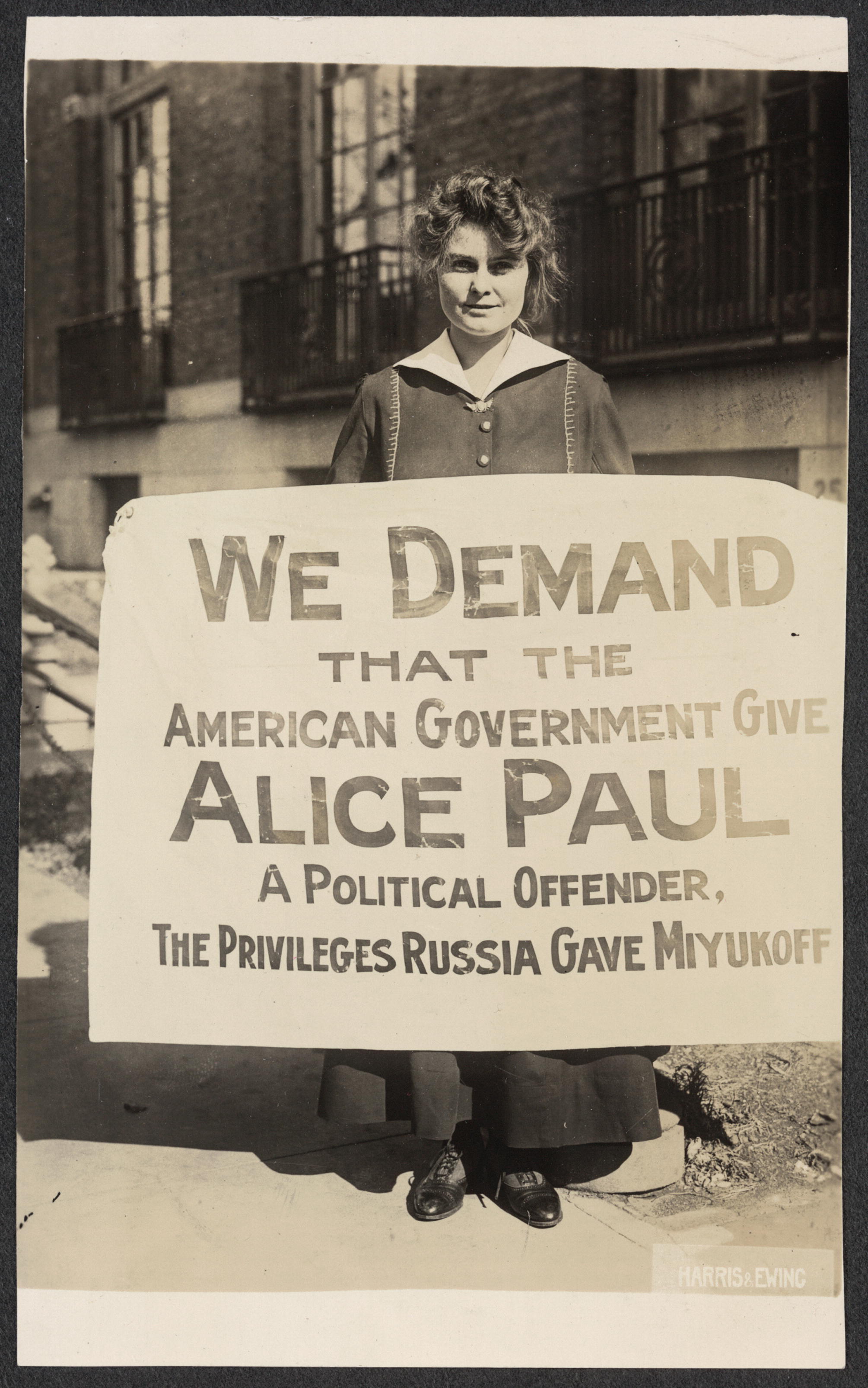

The women picketted for months and were often jailed. They were subjected to brutal treatment. Some who went on hunger strikes suffered force feedings. It’s said that when Wilson heard of the treatment of the suffragettes, this outraged him enough to finally take a stance. It could have also been the support roles that women played throughout WWI, filling domestic jobs once held by men, that gave Wilson the motivation to advocate women’s suffrage. Maybe it was his daughter, Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre, an active suffragette, who was finally able to persuade her father. It could have been a culmination of all three.

In a September 1918 speech to the Senate, Wilson came out publicly to advocate for women’s suffrage. Speaking to the Senators before a vote on the 19th Amendment, he said, “We have made partners of the women in this war. . . . Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” With Wilson’s support, the amendment came within two votes of gaining the two-thirds majority needed to pass.

It would take another year for the 19th amendment to pass through Congress and go to the states. After successful lobbying efforts by Phyllis Younger, who focused her attention on the Senators who had previously voted no, the amendment finally passed.

By 1920, 35 states had ratified the 19th amendment. Only one more state’s action was needed to officially add it to the Constitution. Of the remaining states, the one most likely to ratify was Tennessee. But this was not an automatic conclusion, since Tennessee’s state house was deadlocked 48-48.

Banks Turner changed his vote and bent to the will of his party, the Democrats, because—it was thought—pressure was put on him by the Tennessee governor and Wilson. And Harry Burns, also, changed his vote to a yes. He is mostly remembered because he had been under political pressure to vote in opposition, but changed his vote after his mother wrote him a note that said, “Hurrah and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt.”

Women’s suffrage helped lead to women holding elected public office on the national level. In 1916, Jeanette Rankin of Montana became the first woman elected to the House of Representatives (Montana allowed women to vote in 1914 ). Nellie Ross won the governorship of Wyoming after a special election in 1924. Hattie Caraway was elected to the Senate from Arkansas in 1932. In 1984, Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman to run for Vice President on a major party ticket. She was followed by Sarah Palin in 2008, and Kamala Harris in 2020. Hillary Clinton ran for president on the Democratic ticket in 2016.

Could these women have ever considered shattering the glass ceiling if it hadn’t been for the work of countless women before them, women like Abigail Adams, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, Alice Paul, and all the unnamed women who sacrificed for future generations? I think not. So if a man on the street with a clipboard comes up to you asking to sign a petition to end women’s suffrage, please don’t sign.

Lauren Goepfert is a student in the Master of Arts in American History and Government program at Ashland University. Named the 2018 Madison Fellow for the state of Florida, she now teaches at Longwood High School on Long Island, NY.