Teaching Suffrage with Michelle Adams Alderfer

This month we honor women’s history by highlighting one of our teacher partners. Michelle Adams Alderfer is a 2021 MAHG grad whose Chairman’s Award-winning capstone project was an original play about Tennessee’s ratification of the 19th Amendment. Below is our conversation with Michelle about the process by which Tennessee ratified the amendment and how she created a hands-on, primary-source driven project for her middle schoolers.

Teaching the 19th Amendment

Beginning her capstone project for the Master of Arts in American History and Government, Texas teacher Michelle Adams Alderfer wanted to help her eighth-grade students appreciate American women’s decades-long struggle for voting rights. Middle-schoolers learn about Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who founded the suffrage movement in the mid-nineteenth century. But many never hear the rest of the story. Most eighth-grade American history courses end at 1876, when Reconstruction ends.

Alderfer had always expanded her lesson on women’s rights, carrying it through the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Her students learned that a new generation of activists led by Carrie Chapman Catt persuaded Congress to pass the suffrage amendment in 1919. After this, one more hurdle remained. The constitutional amendment Congress approved had to be ratified by three-fourths of the states.

Ratification, The Last Hurdle for Women’s Suffrage

Sometimes students didn’t grasp the purpose of this last Constitutional requirement. “The founders wanted to ensure the government they diligently worked to establish would not be easily altered,” Alderfer explains. They knew that “the Constitution would need to change as the United States grew and evolved, but they did not think that adaptations should be impulsively made. The ratification process they put in place ensures that any amendment is truly the desire of the American people.”

Still, the lengthy process allows opponents of amendments to deploy a range of legislative maneuvers to frustrate passage. To help students to understand these last obstacles to women’s suffrage, Alderfer decided to dramatize them. Her play, Hurrah, and Vote for Suffrage: A Four-Act Play about Tennessee’s Ratification of the 19th Amendment depicts the crucial weeks in August 1920 when the Tennessee legislature met in special session to consider ratification.

All eyes in the country focused on the debate in Tennessee. If it voted to ratify, it would be the 36th of 48 states to do so, making the amendment federal law. Supporters in Tennessee were divided from opponents not by party affiliation but by deep-seated feelings about women’s proper roles in family and public life. Outside the legislative sessions, suffragists lobbied the lawmakers, handing yellow roses to those who supported the amendment. Opponents handed red roses to lawmakers pledging to vote against it.

Legislative Maneuvers and a Mother’s Letter

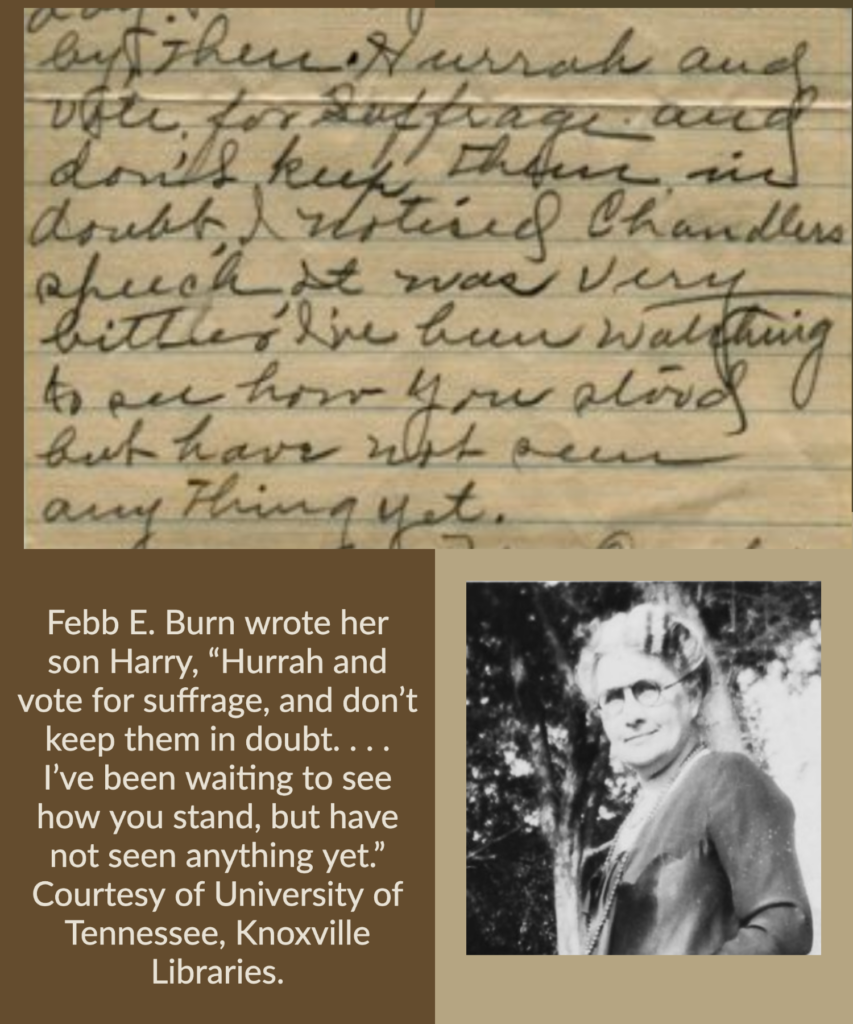

The amendment passed the Tennessee Senate but stalled in the House. Before the House vote, observers counted slightly more red roses in legislators’ lapels than yellow ones. Popular history credits one young red-rose-wearing legislator, Harry T. Burn, with deciding the outcome. At the last minute, he switched his vote—after his mother wrote him a letter asking him to do so.

“I expected students would be engaged by the story of the youngest member of the Tennessee House changing the course of history, especially after learning that he did so at his mother’s urging,” Alderfer said. “Yet the scope of the play grew as I researched the Tennessee vote. Burn’s last-minute vote change is more accurately seen as the culmination of weeks of battles between the suffragists and the ‘antis,’ prior to the special session as well as during it.”

Researching the history, Alderfer read most of the Tennessee House Journal for August 1920. She also read archived newspaper accounts. Initially, she planned to frame the play’s action with “the historical anachronism of a television news broadcast.” Jason Stevens, who advises MAHG students as they write capstone proposals, discouraged that plan. Still, Alderfer “needed a way to explain the action that this generation of students would understand.” She decided to add newspaper reporters to her cast of characters. Watching legislators speak during the House debate, “the reporters could ask each other, ‘Did he just say what I think he said?’”

Using Reporters to Explain the Drama

After reading an early draft of Acts I and II, Alderfer’s faculty advisor, Natalie Taylor, suggested giving the journalists the main roles. “So, I rewrote what I’d already written,” Alderfer said. Now the story flowed easily. “I was so grateful Dr. Taylor made that suggestion!”

One of the play’s main characters, Albert Virgil Goodpasture, wrote a feature story in The Nashville Tennessean that supplied Alderfer with many historical details. The other main character is fictional. “I thought we needed the female perspective,” Alderfer said, so she invented an eager cub reporter named Diana Stanton (giving a nod to the Stanton—Elizabeth Cady—who founded the movement).

Alderfer depicts the two journalists as suffrage supporters who nevertheless try to cover events objectively. They watch public demonstrations for and against ratifications, then watch the legislative machinations from the Senate and House galleries, speculating on the changing game plan of the amendment’s opponents.

Defeating the Last Challenge to Suffrage

Stanton writes daily reports on the proceedings, while Goodpasture takes notes for a post-mortem account of all that happens. The reporters discuss legislative moves to table the motion to ratify or to dismiss it as contrary to the state constitution. At one point, Speaker of the Tennessee House Seth Walker reverses position. An opponent, he sees the vote trending against him and unexpectedly votes to ratify. The reporters conclude that voting to approve will give the Speaker the procedural right to call for a new vote. After the House ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment, anti-amendment activists try a final ploy: they charge that Burn switched his vote because he was bribed. Walker’s plan to call for a new vote suddenly seems a possibility.

In the play’s last act, Goodpasture and Stanton resolve the controversy. They interview the political operatives claiming to have witnessed Burns being offered money. Then they show the operatives affidavits from others who contradict this slander. Finally, they interview Harry Burn’s mother, who speaks proudly of her son and the effect on him of her letter.

Alderfer planned to write a play students might easily perform. In the end, she produced a long, challenging script, thick with rhetorical language. Many of the lines directly quote the words of pro- and anti- activists, as recorded in the newspaper accounts or in the Tennessee House Journal. Hence the play draws an accurate picture of the arguments made by those fighting for and against ratification. Goodpasture and Stanton repeatedly interview Carrie Chapman Catt, who was in fact present in Tennessee in August 1920, coordinating lobbying efforts for ratification. Catt describes the struggle in the stirring, confident language attributed to her by the contemporary press.

Alderfer’s capstone project, which won a Chairman’s award in May 2021, has enriched her lessons on the suffrage movement. During the 100th anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment in 2020, she shared much of her research with students. “I haven’t used the play itself yet,” she says, but, “stay tuned!” In the fall of 2021, she began a new teaching assignment at The John Cooper School in a northern suburb of Houston, Texas. She now teaches American history from 1607 through as much of the 20th century as time allows.

The History Students Need to Learn

With so much to cover, how does Alderfer decide when to speed through history, and when to slow down and dig deep? Alderfer thinks carefully before responding. “Especially as the climate of our country has changed, I’ve become willing to let go of some events we covered before, for the sake of telling a broader story that includes more voices. But I also want my students to find history applicable. They need to understand how history relates to their lives today. That’s why I teach the Constitution in detail. Some teachers might cover the Bill of Rights quickly and then move on. But these are the actual rights of our students. Who knows how they may need to invoke these rights during their lives?”

Alderfer helps students understand the rights the founders guaranteed, as well as the rights later generations recognized and encoded. Because of her capstone work, she now can explain subtler matters that may also affect her students’ lives profoundly—such as “the nitty gritty of the legislative process” women had to navigate before winning the right to vote.