Jonah was walking in circles as he spoke to me – I love it when he does this because I too walk in circles while I process information. He said, “Mrs. Parker, I think Jacob Lawrence was presenting the viewer with an Irish Thesis through his art.” Jonah is an eighth grader who, as part of an assignment, is trying to recreate a missing panel in artist Jacob Lawrence’s series Struggle: From the History of the American People. English and History teachers have long used John Irish’s thesis formula to help students acknowledge the complexity of an argument and organize their writing.

The formula is: X. However, A,B,and C. Therefore, Y. In writing about history, “X” frequently represents the common or traditional view of an event, political movement, or social change. “Y” represents the writer’s differing view, which has been influenced by the discovery of “A, B, and C,”—facts previously excluded from the historical account. The Irish Thesis is useful here because it allows one to consider both how history has been traditionally taught and the potential shortcomings of that perspective.

In his own way—through painting rather than writing—Jacob Lawrence invites viewers of his work to consider different perspectives on American history. He points to the less well-known figures of the past, people whose difficulties and struggles have been overshadowed by our focus on the heroes commonly associated with an event or movement.

Jacob Lawrence and the Great Migration

Teachers are likely familiar with Lawrence’s 1941 series Migration, which brought attention to the mass exodus of African Americans leaving their Southern homes and moving to Northern industrial cities. This movement, the Great Migration, was one of the largest demographic shifts in American history. Lawrence’s parents met on their migration. His mother was born in Virginia and his father in South Carolina. The family eventually settled in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Lawrence routinely heard stories of the hardships of the South and the hopes of the migrating families. In the introduction to his children’s book titled The Great Migration, Lawrence noted, “it was inevitable that I would tell this story in my art”. Today, many teachers use all sixty panels of Migration to teach the rationale, experiences, and consequences of the Great Migration for African Americans and for Northern cities. The choice to leave the farm for the promise of industrial work was difficult. However, according to Lawrence, “out of the struggle comes a kind of power, and even beauty.”

The Struggle Series

The theme of identifying and claiming the power of struggles certainly influenced Lawrence’s later work. In his unfinished series Struggle, which my students are studying, Lawrence claims a role for women, African Americans, immigrant workers, and the indigenous in the story of our Revolution and Founding. He reimagines the vignettes of history most commonly taught in textbooks and by teachers, offering powerful images to compete with the traditional interpretation found in many textbooks. Lawrence painstakingly examined the history of the United States in order to create what he envisioned as a sixty panel series of paintings depicting the development of our country. In approaching this complex work, Jonah’s idea is worth examining.

While Lawrence studied American history, he witnessed the impact of new media—television—on American culture, and how it gave wings to protests organized in the modern Civil Rights movement, while exposing the nefarious tactics associated with McCarthyism. The tenor of the time in which Lawrence painted this series can be not only observed but also deeply felt by viewers of his work. I know this because I was one of about twenty teachers who participated in a weekend colloquia sponsored by Teaching American History centered on the Lawrence paintings and the primary sources that inspired them. The weekend was especially relevant at a moment when the nation debated the best way to teach the history of our country.

“Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death”

Lawrence begins the series with a depiction of Patrick Henry’s famous “Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death” speech. The first painting is captioned with a question Henry posed in his pleas for liberty: “Is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?” These eloquent words were passionately delivered by a man who at the time of the speech enslaved over eighty people. The country and the world are certainly better for Henry having expressed those sentiments, but the hypocrisy is glaring. The scene as depicted by Lawrence shows Henry speaking in a room with black walls and filled with people; the prominent black wall to which Henry appears to point is dripping with blood. Throughout his career in both Virginia and national politics, Henry struggled with the contradiction. In a 1773 letter to abolitionist Robert Pleasants, Henry made no excuses for his actions:

Is it not amazing, that at a time, when the rights of humanity are stated and understood with precision, in a country, above all others, fond of liberty, that in such an age, and in such a country, we find men professing a religion the most humane, mild, gentle, and generous, adopting a principle as repugnant to humanity, as it is inconsistent with the bible, and destructive to morality? Every thinking, honest man rejects it in speculation, how few in practice from conscientious motives!

Would anyone believe that I am the master of slaves of my own purchase? I am drawn along by the general inconvenience of living here without them. I will not, and cannot justify it. However culpable my conduct, I will so far pay my devoir to virtue, as to own the excellence and rectitude of her precepts, and lament my want of conformity to them.

Crossing the Delaware through Lawrence’s Eyes

All subsequent panels display pivotal points in early American History through the brushstrokes of a man questioning our understanding of ourselves. For example, when I recall the story of Washington crossing the Delaware, I see the event as Emanuel Leutze painted it in 1849: with the image of a tall, proud, fearless general atop a boat being rowed by various men with a yet to be commissioned flag fluttering behind them. In contrast, Lawrence focuses on the soldiers who made the crossing rather than on Washington himself. The panel displays boats being thrown about in frozen waters while bundled soldiers crouch beneath blankets against the elements. Lawrence based his painting on an account by soldier Tench Tilghman, who wrote in his diary: “We crossed the River at McKonkey’s Ferry 9 miles above Trenton . . . .the night was excessively severe . . which the men bore without the least murmur . . . .” While Leutze romanticizes the crossing, Lawrence shows us what it cost Washington’s troops. I think Washington would prefer Lawrence’s depiction.

The Dignity of Sacajawea

For me, the depiction of Sacagewea, the Lemhi Shoshone woman who guided Lewis and Clark through the most dangerous part of their exploratory mission, was one of the most poignant. Lawrence paints a meeting between Sacagewea and her estranged brother. Prior to viewing Lawrence’s work, I had not considered Sacagewea’s family, beyond her child commonly pictured as carried on her back; I did not know she had a brother. My memory recalls the image engraved on coins—she is shown as a courageous mother, selflessly assisting the white explorers—not as a member of a closely knit tribe whose way of life was threatened by the advance of white men west. Again, a romanticized version of a perilous journey mired with struggle. In this panel Lawrence uses striking colors to underscore the strength and dignity of Sacagewea’s family and people. The caption for this panel is: “In all of your intercourse with the natives, treat them in the most friendly and conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit….” Lawrence took the line from an instructional letter from President Thomas Jefferson to Lewis and Clark. The irony is stunning. Lawrence juxtaposed the struggle of Native Americans with the often conveyed heroics of Lewis and Clark, causing viewers to expand their understanding of a seminal moment in history.

Jacob Lawrence and the American Conversation

Struggle: From the History of the American People is a visual representation of the discussions taking place across the country about how race, progress, and the story of America should be taught to students. Questions about how we understand the American promise of liberty and which voices should be elevated are causing consternation for teachers and are being used by opportunistic politicians to drive wedges of separation between citizens. It took the sagacity of a fourteen-year-old to put this into perspective for me. Just as the evolution of television drew back the curtains on the Jim Crow South during Lawrence’s time, the internet has drawn back the curtains on the experiences of marginalized communities and their contributions to the fabric of America in Jonah’s time. Gone are the days of teachers being the gatekeepers of knowledge.

Ultimately, I think Jonah and Jacob Lawrence are right. Perhaps, the Irish Thesis presented in Lawrence’s work is: The American Revolution and Founding were divinely inspired achievements of monumental proportions. However, our history is rooted in struggle: the struggle of great men of conscience to uphold ideals of liberty, the struggle of the indigenious and enslaved to survive and preserve their culture, and the struggle of mankind to realize the promise of the American Experiment. Therefore, as teachers, we must always continue to learn and tell the stories defining the entirety of the American Struggle.

Amy Parker is a Middle School history teacher at Creative Learning Academy in Pensacola, Florida. She holds a Master of Arts in American History and Government from Ashland University and a Master of Science in Educational Leadership from Barry University. She was Florida’s 2014 James Madison Fellow and has won awards for her innovation in the classroom.

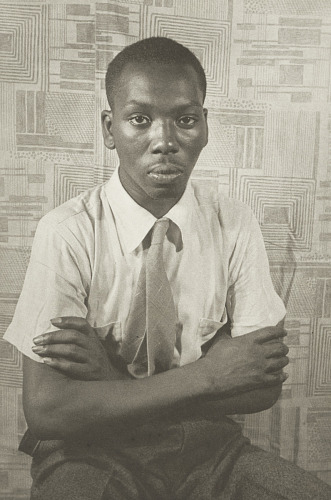

Jonah Steiner is an eighth grade student at Creative Learning Academy in Pensacola, Florida. A gifted student of history with a knack for creative storytelling, he serves as Student Body President.