Juneteenth: Our Newest Federal Holiday

Some of my favorite teaching opportunities are when I get to teach the history behind American holidays. Frequently (usually after the third or fourth holiday lesson) I get the slightly off-topic question, “what holiday would you add to the calendar?” And for years I’ve had a quick and easy answer: Juneteenth. Of course, since Juneteenth became a federal holiday last year, I will need to find a new answer to that question. But for now I’d like to take an opportunity to celebrate its addition to the federal calendar.

The History of Juneteenth

The basic historical sketch of Juneteenth has become broader public knowledge in recent years, but let’s recap:

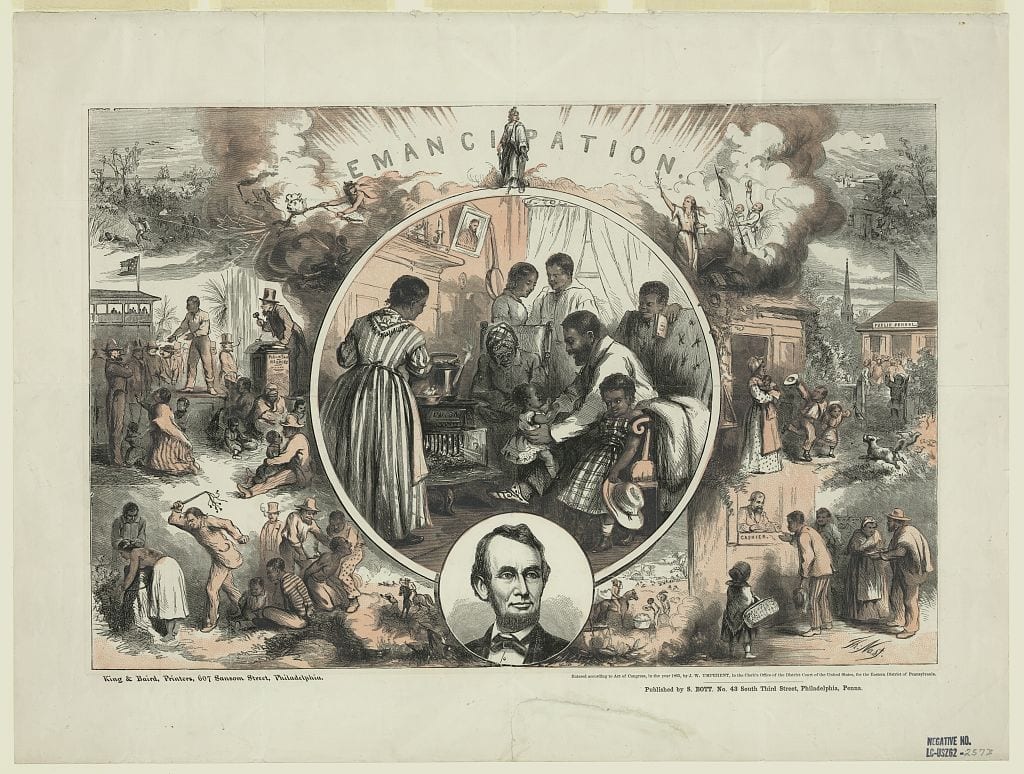

The direct reference is to June 19, 1865, when Union Major-General Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3 in Galveston Texas, emancipating some of the last African Americans held in chattel slavery. It is true that Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had been issued two and a half years earlier, and announced nearly three years earlier. However, as mapmaker and publisher Lucius Stebbins put it in 1864, the order “could [only] reach the downtrodden and oppressed … through the faithful soldier, without whom the Proclamation would ever have remained a dead letter.” Indeed, by the time Granger delivered his message, Lincoln was dead and the military conflict had ended. Yet many rebel slaveholders had no intention of giving up the institution (with the challenges to the economic and social order that change would entail). So Granger’s order enforces Lincoln’s proclamation: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property.”

This historical sketch is instructive enough to be essential learning for American history students, but perhaps not enough alone to justify a holiday. And it is worth listening to some good-faith critiques of memorializing Juneteenth.

Critiques of Juneteenth

One thoughtful argument against making Juneteenth a federal holiday emphasizes its inaccuracy. While Juneteenth honors emancipation made real, it is not the case — as is sometimes mistakenly asserted — that Juneteenth “commemorates when the last enslaved African Americans learned they were free.” While black Texans were freed from illegal slavery on Juneteenth, some African Americans were still legally held in bondage on that date. This is because Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 affected “the States and parts of States … in which the people … shall then be in rebellion.” Texas was a rebel state as of that date, so the Juneteenth ordinance applied over two years later. But parts of the Confederacy that had been subdued pre-Proclamation (e.g. the state of Tennessee, city of New Orleans, and some eastern parts of Virginia) were exempted. Furthermore, slaveholding states that remained in the union — Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, and the breakaway state of West Virginia — were also excluded.

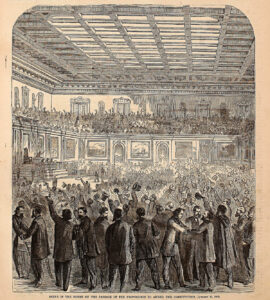

June 19th doesn’t hold the same historical significance to these places, so some critics propose December 6th — the ratification date of the 13th Amendment in 1865 — as an alternative. It expresses a more thorough commitment: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude … shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” And yet even the 13th doesn’t capture the full story. For example, Indian Territory’s complex political status meant that the 13th amendment didn’t quite apply there. As historian Eric Foner notes, before their forced displacement the Five Tribes of Indian Territory “made great efforts to become everything republican citizens should be” according to standards set around them by Southern society. For many Native Americans, this entailed “becoming successful farmers, many of whom owned slaves.” The quasi-sovereign status of Indian Territory meant that emancipation didn’t come to those black Americans enslaved by the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole nations until the Reconstruction Treaties of summer 1866.

Even adding this detail, the date when the last American was freed from chattel slavery is almost certainly lost to history (to say nothing of quasi-slave statuses imposed through legal-technical loopholes like the “punishment for crime” exception in the 13th Amendment). So any holiday is necessarily symbolic. Which returns me to the value of Juneteenth. First of all, it is a day that the formerly enslaved chose themselves. Furthermore, it is not simply a story of June 19, 1865. In fact, it is much more a story of 1866, and of June 19th in subsequent years.

The social history of Juneteenth makes it truly remarkable. In fact, Granger’s 1865 ordinance downplayed its own significance at some points, and made demeaning presumptions about the newly freedpeople in others. The order did not anticipate a civil role for black Texans beyond “hired labor” and encouraged them to “remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages” while informing them “that they will not be supported in idleness.” In short, Granger announced a new legal order while challenging the social order as little as possible.

Celebrating Emancipation

But black Texans refused to downplay the significance of emancipation. The very next June 19th, in 1866, they began holding public celebrations, defiantly reciting the Emancipation Proclamation and other literature recounting the freedom struggle, and celebrating with games, dancing, and fellowship. Over time, they began purchasing “emancipation grounds” to hold these celebrations (a number of which still bear the name “Emancipation Park” in various Texas cities).

And they maintained this grassroots protest celebration, through Reconstruction and its overthrow, through the darkest periods of lynch law and Jim Crow, through the Civil Rights era. Over this time, the June 19th celebration spread across Gulf-adjacent Southern states, and eventually across the country with the Great Migration of the early-mid 20th century (taking particular hold in black communities in California). Black communities kept Juneteenth alive for 115 years before its first official state-level recognition, by Texas, in 1980. Four states had formally recognized the holiday by the time the first edition of Ralph Ellison’s posthumous second novel was published in 1999 with the title Juneteenth, bringing a boomlet of national attention to the holiday and supporting new momentum for over thirty states to recognize Juneteenth (at least ceremonially) in the subsequent decade. The final momentum toward a federal holiday came in 2020, with the protests of George Floyd’s murder preceding and overlapping with the holiday that year. The following year, Congress passed and President Biden signed into law a bill making Juneteenth the 11th annual federal holiday.

Juneteenth: Recommitting to a Better Future

There is no more worthy addition to the federal calendar than a holiday demonstrating the ability of people to make something real of freedom by enacting it in deeds and action. Juneteenth does not honor emancipation with empty platitudes. The holiday exemplifies the lesson that Cesar Chavez took from the work of Martin Luther King Jr.: “freedom is best experienced through participation and self-determination.” Honoring the story of purpose and joy represented by Juneteenth — a holiday that has survived and thrived against odds and expectations — is an opportunity to commemorate the past while recommitting to the need perpetually to seek a better future.

Additional Sources

Congressional Record Service. “Juneteenth: Fact Sheet.” Version 21, updated 2021.

Foner, Eric. Give Me Liberty: An American History, Brief Sixth Edition. New York: W.W. Norton, 2020

Holzer, Harold, Edna Medford & Frank Williams. The Emancipation Proclamation: Three Views. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

Pennington, William D. “Reconstruction Treaties.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society Online.

Texas State Library & Archives Commission. “Texas Observes Juneteenth.”