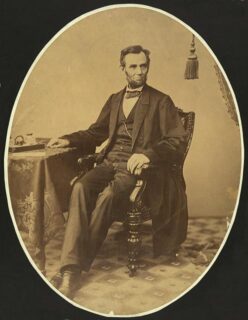

Lincoln's Reconstruction Plan

One hundred fifty years ago this fall, advance planning for the reconstruction of the rebelling Southern states began. In the fall of 1863, after the victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, Congressmen assumed the war would soon end. President Lincoln had regarded the secession of southern states from the union as logical contradiction of their original binding ratification of the Constitution and maintained that the Civil War was fought primarily to prevent the union’s dissolution. So it should perhaps not be surprising that Lincoln proposed a means of readmitting states when only a small minority of their constituents—10 %—voted to reestablish republican governments that acknowledged the authority of the Constitution. Those forming these governments must swear allegiance to the Union and also swear their acceptance of acts of Congress and Presidential proclamations regarding slavery—that is, the reentering states must accept emancipation. To his non-abolitionist critics, Lincoln had justified emancipation as a war measure; now he stated that to abandon the decision to free the slaves “would be not only to relinquish a lever of power, but would also be a cruel and an astounding breach of faith.”

Although radicals in the Republican party wanted a more detailed and prescriptive plan, Lincoln’s ideas on reconstruction were met with initial approval when he discussed them in his Annual Message to Congress on December 8, 1863, issuing his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction on the same day. But Lincoln’s moderate proposal for re-admittance of the seceded states did not, as he hoped, persuade rebels to cease hostilities. Sixteen more months of war would follow, after which Lincoln would be assassinated and radical Republicans would push through sterner measures.

Below is an excerpt from the Annual Message to Congress:

Looking now to the present and future, and with reference to a resumption of the national authority within the States wherein that authority has been suspended, I have thought fit to issue a proclamation, a copy of which is herewith transmitted. On examination of this proclamation it will appear, as is believed, that nothing is attempted beyond what is amply justified by the Constitution. True, the form of an oath is given, but no man is coerced to take it. The man is only promised a pardon in case he voluntarily takes the oath. The Constitution authorizes the Executive to grant or withhold the pardon at his own absolute discretion; and this includes the power to grant on terms, as is fully established by judicial and other authorities.

It is also proffered that if, in any of the States named, a State government shall be, in the mode prescribed, set up, such government shall be recognized and guarantied by the United States, and that under it the State shall, on the constitutional conditions, be protected against invasion and domestic violence. The constitutional obligation of the United States to guaranty to every State in the Union a republican form of government, and to protect the State, in the cases stated, is explicit and full. But why tender the benefits of this provision only to a State government set up in this particular way? This section of the Constitution contemplates a case wherein the element within a State, favorable to republican government, in the Union, may be too feeble for an opposite and hostile element external to, or even within the State; and such are precisely the cases with which we are now dealing.

An attempt to guaranty and protect a revived State government, constructed in whole, or in preponderating part, from the very element against whose hostility and violence it is to be protected, is simply absurd. There must be a test by which to separate the opposing elements, so as to build only from the sound; and that test is a sufficiently liberal one, which accepts as sound whoever will make a sworn recantation of his former unsoundness.

But if it be proper to require, as a test of admission to the political body, an oath of allegiance to the Constitution of the United States, and to the Union under it, why also to the laws and proclamations in regard to slavery? Those laws and proclamations were enacted and put forth for the purpose of aiding in the suppression of the rebellion. To give them their fullest effect, there had to be a pledge for their maintenance. In my judgment they have aided, and will further aid, the cause for which they were intended. To now abandon them would be not only to relinquish a lever of power, but would also be a cruel and an astounding breach of faith. I may add at this point, that while I remain in my present position I shall not attempt to retract or modify the emancipation proclamation; nor shall I return to slavery any person who is free by the terms of that proclamation, or by any of the acts of Congress. For these and other reasons it is thought best that support of these measures shall be included in the oath; and it is believed the Executive may lawfully claim it in return for pardon and restoration of forfeited rights, which he has clear constitutional power to withhold altogether, or grant upon the terms which he shall deem wisest for the public interest. It should be observed, also, that this part of the oath is subject to the modifying and abrogating power of legislation and supreme judicial decision.

The proposed acquiescence of the national Executive in any reasonable temporary State arrangement for the freed people is made with the view of possibly modifying the confusion and destitution which must, at best, attend all classes by a total revolution of labor throughout whole States. It is hoped that the already deeply afflicted people in those States may be somewhat more ready to give up the cause of their affliction, if, to this extent, this vital matter be left to themselves; while no power of the national Executive to prevent an abuse is abridged by the proposition.