Literary Reactions to the Harlem Riot: 80 Years Later

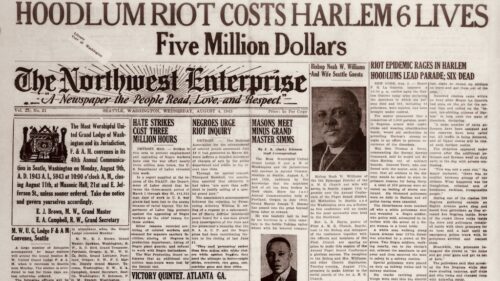

In August 1943, a riot occurred in Harlem when an African American soldier, Robert Bandy, objected to the arrest of Margie Polite on charges of disorderly conduct and was shot by a police officer. As Kathy Pfeiffer explains, two of the great African American writers of the twentieth century reflected on these events.

In August of 1943, as racial tensions simmered along the streets of Harlem, Langston Hughes was in residence at the prestigious Yaddo artist colony. Just a year before, he had broken the segregation barrier as the first black artist ever invited to join the distinguished Saratoga Springs community. The Harlem riot broke out during his second residency, and Harlem was on his mind, in spite of the physical distance separating him from the city he loved. In “The Ballad of Margie Polite,” Hughes captures the complexity of the riot that was sparked by one woman’s refusal to submit to police control, and he honors the values, voices, and lives of his fellow Harlemites. Because the poet speaks in vernacular, his thoughts are easily accessible, like in so much of Hughes’s writing. Yet its folksy recounting of the terrible event is also rueful and nuanced, thereby masking the specificity of its measured but devastating critique.

The irony was not lost on Hughes that a woman named “Polite” would be so rowdily outspoken, and with such consequences. The poem’s opening lines offer a mischievous surface of rhyming wordplay “If Margie Polite/Had of been white/She might not’ve cussed/Out the cop that night” – as they speak to a stark truth about longstanding police harassment of Black women. The poem’s speaker is a first-person witness to the event, a folk narrator whose vernacular speech has no interest in proper grammar. “Margie warn’t nobody/ Important before -/ But she ain’t just nobody/ Now no more.” In this way, the narrator is identified with those Harlem “hucks” who are disdained by the image conscious “race leaders;” these leaders, in turn, appear embarrassed by the rioting folk. “They didn’t kill the soldier,/ A race leader cried,” an observation that, in Hughes’s view, misses the point entirely. “Somebody hollered,/ Naw! But they tried!” Intra racial class tension aligns NAACP dignitaries like Walter White with Mayor LaGuardia, both of them riding in sound trucks throughout Harlem, shouting down the rioters. Hughes expressed his disdain for such race leaders privately at the time, noting dryly to a friend, “Sugar Hill is very mad at Harlem about the riots. The letters I have received from the better colored people practically froth at the mouth. It seems their peace was disturbed even more than the white folks.’” (Remember Me to Harlem, 218) The poem’s repeated display of exclamation marks reflects Hughes’s own emphatic feelings about the event, as does the recurring capitalization of MARGIE’S DAY; in titling his poem a “Ballad,” Hughes memorializes Margie Polite as a folk heroine.

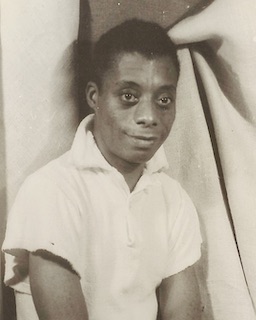

In contrast to the visually and verbally accessible lines of Hughes’s poem – with its short stanzas and everyday speech – James Baldwin’s account of the riots is visibly dense: long paragraphs are unbroken by any dialogue or by the inclusion of white space that gives readers a minute to breathe. The only two breaks we see are those separating the essay’s numbered sections. In this way, Baldwin pulls us into his writing and into his life, both of which are intense, complex, and requiring our focused attention. Unlike Hughes, who experienced the Harlem riot from the distance of Yaddo, Baldwin was deeply enmeshed with the event, which overlapped with his nineteenth birthday, his father’s death, and his youngest sister’s birth.

Such an astonishing confluence of major life events demand serious consideration, and when Baldwin answers that demand, he does so in first person narrative nonfiction, employing the classic essay structure invented by Montaigne centuries ago. The choice of genre is important, because it demonstrates his mastery over a classical literary form that is traditionally associated with aristocratic discourse. And just as his essay’s formal qualities honor this literary history, the story he tells also looks to the past to understand the present and prepare for the future. At times, this rhetorical movement is explored personally, through reflections on his father’s life: Baldwin recalls him as handsome, imagines him among “African tribal chieftains” and then considers how the relentlessness of racism infected him like an illness, making him “chilling,” “indescribably cruel” and so very “bitter.” “He claimed to be proud of his blackness,” Baldwin recalls, “but it had also been the cause of much humiliation and it had fixed bleak boundaries to his life.” In exploring the limitations his father encountered, we soon see, Baldwin is also explaining Harlem, moving through space as well as time, connecting the Jim Crow past of his father’s life to the imprisoning boundaries of the 1943 ghetto. He moves forward in time as well, as he sits at his father’s funeral and considers the future: “Further up the avenue his wife was holding his newborn child. Life and death so close together, and love and hatred, and right and wrong, said something to me which I did not want to hear concerning man, concerning the life of man.”

In the essay’s most vivid and arresting scene, Baldwin describes an instance when, after the repeated public humiliation of being refused service in a restaurant, he hurls a waterglass in rage, shattering a mirror. He recognizes that the most shocking insight of that evening was not only the violence he escaped himself (white friends helped him run away from the mob that quickly formed) but the violence he himself could have caused, noting, “my life, my reallife was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart.” When Baldwin tells us about the glass he has shattered, he aligns himself with Harlem’s rioters, who have “smashed open” all of Harlem’s white businesses. Lest we miss the connection, he repeats the word, searing its image in our minds. “Harlem had needed something to smash,” he notes. “To smash something is the ghetto’s chronic need.” Baldwin thus offers us an unexpectedly personal insight about how the persistence of racism and segregation fueled the rebellious uprising that exploded on August 1.

Kathleen Pfeiffer is an Honored Visiting Graduate Faculty Member at Ashland University and Professor of English and Creative Writing at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan. She teaches courses in American literature, African American literature, the Harlem Renaissance, biography, memoir, and creative nonfiction.